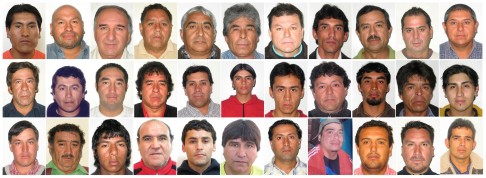

Survivors of 2010 Chile mine disaster pick right man to tell their story

Journalist Héctor Tobar secured the trust of all 33 of the miners who had been trapped underground for 69 days - and the resultant book is riveting

Job interviews can sometimes be marathons. But it’s rare to find one quite like what journalist Héctor Tobar went through on his way to becoming the chosen author for Deep Down Dark: The Untold Stories of 33 Men Buried in a Chilean Mine, and the Miracle That Set Them Free.

Tobar, a journalist and author, is the son of Guatemalan immigrants and a Los Angeles native. He is known for his writing, his reporting, his affability and his empathy for the working class.

The miners, trapped underground in a collapsed Chilean mine for 69 days in 2010, endured an ordeal that put the whole world on watch. They had made a pact as they waited underground that they would choose one person to tell their collective story. The miners’ lawyers retained the William Morris Endeavor talent agency. The agency contacted Tobar, a long-time writer for the Los Angeles Times and author of three previous books. Then Tobar had to go to Chile, to meet the miners and secure their trust. All 33 of them.

The miners picked Tobar, and the result is a classic work of adventure reporting. Deep Down Dark was a non-fiction finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, riveting in its storytelling, meticulous in its reporting and its empathy for the miners. It’s just been released in paperback.

Tobar, who teaches journalism at the University of Oregon and writes a monthly column for The New York Times, talks about his extraordinary odyssey.

How did you win the miners’ trust?

I felt right away I was in the presence of people who had been through an extraordinary experience. I tried to communicate my sense of compassion, empathy and my curiosity about mining culture and their families, their jobs and their children. I communicated to them that I really cared about them. I think they were exposed to a lot of people (in tabloid journalism) who wanted to tell their story in a melodramatic way. I tried to communicate that I wanted to learn as much as I could about them.

My first questions were about mining culture. I had to learn how the mine worked. As I asked my questions, I could also begin to see the natural structure. There was the first 17 days, from when they were trapped to when they were discovered. There was a certain purity to the way they talked about it, and what happened to them. And then there was what happened to them between the time the drill broke through to when they got out. That was more funny and absurd and strange. The first part was about the better part of their nature, and the second part was about the darker part of human nature.

It was so interesting to see how different men stepped forward to become leaders – not necessarily the men you would have expected. The moment early on when some men broke into the emergency food supplies and ate them, when the group had no idea how long they would need to make the food last – that seemed like a turning point.

Without a doubt, the very strong personalities of Mario Sepúlveda and a couple of other men were absolutely essential. They were people who were assertive and communicated what had to be done. Without their leadership, it would have descended into chaos. And then there was faith, to have men who could say, we need to be strong, but we need to call on a higher power, to call on the faith we have in our family and our country.

I did make several visits to the San José mine. The mine is closed but you can walk up to the entrance. You can see the tunnel that the men went in, though only a few feet into it. I went just to be there. It’s the middle of the desert, which requires you to travel for an hour through this moonscape. That was a pretty unforgettable experience. I got to enter a mine close by that was similar. I went down with the filmmakers [a few hundred metres]. That really showed me the abyss. Finally, I had access to videos the men shot, too. The first video they made after [the rescuers] broke through, with a camera the government sent down, that really showed their physical deterioration.

Were there characters in the stories that were your favourites, that helped you put everything together?

I kept on hearing the story about this woman [Maria Segovia], who was dubbed mayor of the camp. [The miners’ families formed a camp outside the mine and lived there during the rescue effort.] It turned out that she lived eight or nine hours on the other side of the desert. She took a bus and came to speak to me at her brother’s house. She was just a wonderful interview. She transported me back in time to where her brother [Dario Segovia] and she grew up, the fortitude that growing up poor required, the belief that “I am going to fight to survive, and I am not going to allow anything to tear that apart”. She gave me the material and the confidence and the vision to put that into the story.

Tribune News Service