Book review: Portugal’s bloody empire in Africa and Asia – and the making of the modern world

Driven by religious zeal, willing to employ deadly force and indifferent to the civilisations they turned upside down, Portugal’s explorers emerge from Conquerors in a form very familiar to contemporary eyes

by Roger Crowley

Faber & Faber

“Had there been more of the world,” wrote Luis de Camoes of the Portuguese explorers, they “would have discovered it”. That’s a line from Roger Crowley’s fantastic new narrative history, Conquerors: How Portugal Seized the Indian Ocean and Forged the First Global Empire.

Crowley is out to reset the primacy of Columbus and the Spanish discovery of the Americas that resides in contemporary Western society. The age of exploration was a European endeavour, but particularly an Iberian one. The Portuguese explorers were the ones who did the bulk of the discovering.

Moreover, as Crowley relates, Portuguese swashbuckling penetrated the heart of Asian commerce and achieved a stunning dominance there. The Portuguese, within a matter of years, had created the first Western-dominated world empire since Alexander the Great. Their achievement was Act One in the saga of the rise of the West and what a bloody, thrilling and unlikely victory it was.

After reading Conquerors, it’s hard to understand why the Spanish effort is celebrated while the Portuguese story is not. As an American, I grew up with the story of Christopher Columbus, whose voyage in 1492 is held to have changed the world. “Columbus Day” remains an American holiday. Historians such as Jared Diamond and Charles Mann have focused on the “Columbian Exchange”, in which the Americas were joined to the rest of the world. This initiated exchanges of plants, animals, cultures and diseases that had profound effects on both hemispheres. It was the beginning of the modern age.

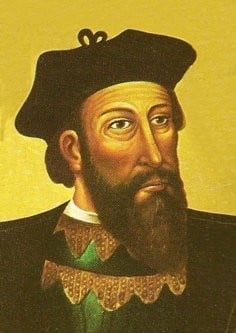

But Crowley would like to remind us that the Spanish empire in the Americas was an exercise in catching up to the Portuguese, who had spent decades attempting to get around Africa. That initiative finally succeeded in 1488. The distance that Vasco da Gama travelled to reach Calicut in India – his was the first European journey to make landfall on the subcontinent – was three times the distance of Columbus’ journey to the Caribbean – or the “West Indies”, as he called them.

By 1506, the Portuguese had established forts in key ports along the east African and Indian coasts, and their ships were returning to Lisbon brimming with spices, gold and other luxury goods. Lisbon quickly changed from a backwater into a cosmopolitan capital, its riches attracting all sorts of merchants, craftsmen and artists from all over Europe.

Meanwhile, as Crowley notes, in May 1506, Christopher Columbus, the agent of Spain’s rivalry with Portugal, died in Valladolid still convinced that he had reached the Indies.

But the Portuguese did not achieve all of this by participating in the Asian trading networks upon which they stumbled. The explorers were amazed by what they encountered in the Indian Ocean. The wealth of even minor port cities was beyond anything they had ever seen. (The first mission to Calicut was humiliated by its lack of anything worth trading.)

Murdering Muslims to terrify enemies was a routine tactic. Albuquerque wrote to his king, Manuel: ‘Our Lord has done great things for us … I have burned the town and killed everyone. For four days without any pause our men have slaughtered’

Muslims and Hindus, although often rivals, had achieved a fairly harmonious balance of power. Although Muslim armies in Ottoman Turkey and Egypt were tough, and its navy in the eastern Mediterranean formidable, the Indian Ocean was a demilitarised neutral zone, in which free trade and tolerance held sway.

The Portuguese could have joined this network with minimum fuss, and were initially welcomed to join in commerce, if they had anything worth selling. But their pathetic wares could fetch nothing valuable in return. In any case, the Portuguese were not soft-power types. They were hard, hard men.

Although economics was part of the strategy (the Iberian quest for India was partly to undermine a monopoly on trade held by the Venetians, on the European side, and the Ottomans on the Asian side), it was combined with a desire for crusading against the Muslim enemy. The Portuguese travelled out of a messianic zeal to wipe out Islam.

Murdering Muslims to terrify enemies was a routine tactic. Albuquerque wrote to his king, Manuel, who also believed he was on a godly mission to defeat Islam): “Our Lord has done great things for us … I have burned the town and killed everyone. For four days without any pause our men have slaughtered … wherever we have been able to get into we haven’t spared the life of a single Muslim. We have herded them into the mosques and set them on fire … We have estimated the number of dead Muslim men and women at six thousand. It was, sire, a very fine deed.”

Any thinking person in the Indian Ocean of the 15th and 16th centuries, Muslim or Hindu, found the Portuguese intrusion unfathomable. When Vasco da Gama seized merchant shipping, the merchants assumed that, as with other pirates, the Portuguese would release them unharmed in return for ransom. Too late, to their horror, did they realise Albuquerque was only interested in burning them alive. Even some of the Europeans in da Gama’s entourage were appalled, but the crown smiled on such acts – and they did prove effective.

Nor could any of the status quo powers bordering the Indian Ocean have foreseen the Portuguese triumph. The Muslim and Hindu kingdoms were ancient and wealthy, and engaged one another in long-held traditions. The last time a strange fleet had disrupted the Indian Ocean, it had been the Chinese treasure ships of the early Ming dynasty. But although the Chinese fleet had certainly awed local potentates with its vast size and technological prowess, the Chinese had been interested in what today would be termed “soft power”. The local princes duly acknowledged the superiority of Chinese culture, pledged themselves as vassals, and engaged in commerce. Although the treasure ships were a novelty, they were a continuation of longstanding relationships throughout Asia. In the event, the Ming dynasty turned inward and bothered the Indian Ocean no more.

Portugal, on the other hand, appeared to Asian princes as a bizarre backwater. The pathetic nature of the goods the first Portuguese missions brought suggested poverty, both material and cultural. The Portuguese, however, possessed seafaring and military technology that had leapfrogged anything Asians had ever seen. Moreover, they came with a crusading mentality. Their agenda baffled Asian powers, whose internal wars followed certain norms and a regulated sense of spoils. The Portuguese seemed to have no limits to their ambition, their greed and their cruelty.

The Portuguese tactics, mindset and success took a form of what today is called asymmetrical warfare. They used technology and the confusion among status quo powers to achieve their goals, which sparked the ascent of Western civilisation for the next 500 years.

Crowley writes of Portuguese ambition: “If its inspiration was medieval eschatology about divine providence and the end of the world, its strategy was drawn from the most contemporary grasp of the known world, and its scale was planetary.”

The example of the Portuguese conquest of the Indian Ocean should give us pause. It sets a precedent for unlikely, seemingly backward societies using terror to upend the established pattern of international relations. The feckless Asian response is a warning that the West, Russia, Turkey, Iran and other powers make themselves vulnerable if they allow rivalries to create an opening for Sunni fundamentalists which the establishment of Islamic State suggests has already happened.

The biggest difference, and the one that must give us encouragement in the face of Islamic terror, is that the Portuguese were not just terrorists: they were also explorers and scientists. Their marauding connected the world in profound ways. “As they went,” Crowley writes, “they mapped, they learned languages and they described, with a ‘pen in one hand, a sword in the other’.” Scientists joined these expeditions; among the treasures being sent to Lisbon was knowledge.

Portugal also broke the Venetian lock on trade with the East, which had enormously positive economic effects. Today’s Islamic warriors in Syria and Iraq, so far as I can tell, are solely bent on murder and backward zealotry: they haven’t contributed anything constructive to their own societies, nor to ours. Western civilisation survived the September 11 attacks on New York; it will survive the recent killing spree in Paris. Nonetheless, it is a sobering example of how a relatively small band of determined murderers who are certain God is on their side can upend civilisation.

There is no question that the Portuguese conquerors were brave, intelligent and audacious, and played a crucial role in creating our modern, Westernised world. But Crowley’s bloody tale makes it also clear, to me at least, that these weren’t the good guys.

Asian Review of Books