Colm Tóibín: ‘There are no 19th century ballads about being gay’

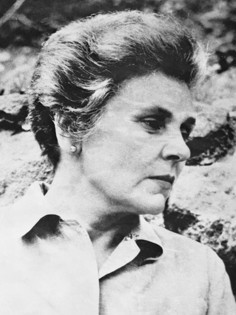

The prolific Irish writer, whose most recent book on the poet Elizabeth Bishop has just been nominated for the National Book Critics Circle Award, reflects on the relationship between concealment, disclosure and art

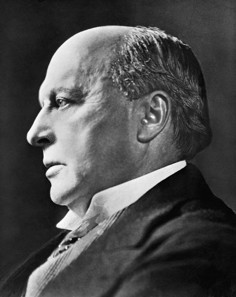

Henry James, Elizabeth Bishop … these seem to be writers whose works weren’t enough for you. You needed to know everything about their lives, to discover them and their works fully.

In both of those cases, I think without knowing it, I had a very intense reading experience aged between 17 or 16 and 21. Those five years, without knowing, without thinking about it, just picking up books and finding some books that affected me in a way that stayed with me. Books later on didn’t affect me as absolutely as these books did. But I am talking about the poetry of Bishop. I knew nothing about her. I knew she lived in Brazil, but I didn’t know anything about her private life at all. And similarly with Henry James, I simply loved the books; then later, I had a sort of funny curiosity. In Bishop’s case, it is really about writing about her letters, and in the case of James, it was attempting to grapple with the whole idea of the relationship between his homosexuality and his work.

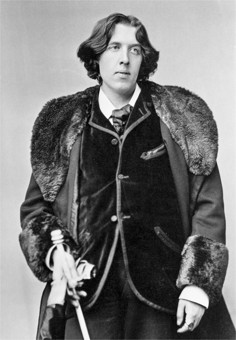

Yes, and this happened by accident to a large extent where I began to write for the London Review of Books and they would send me these biographies. And I would settle into them and try to grapple with the relationship … in the case of Thomas Mann, I have written a few times about the peculiar strangeness of that life, a life in exile, and again we’re talking about sexuality, and the work. And also someone like Oscar Wilde. In the case of Wilde, it is quite difficult to separate Wilde the man and Wilde the artist. That he became himself a sort of work of art and a very tragic work of art, a doomed work of art, nonetheless his own story seemed as powerful as any of the stories he actually wrote.

Yes, in other words, you are finding something absolutely fascinating going on in the time before gay liberation in Europe and America, when history becomes a dotted line to the past, rather than a direct line. These lives are very interesting for us because we do not have many other examples about what it is like to be homosexual in the 1890s. Other than writers, because people kept their letters, they wrote diaries, books, so you can see how they navigated these very difficult waters, all of them in different ways. And it is interesting how much they withheld or disclosed, again you are talking about all that drama between concealment and disclosure. Someone like Graham Greene, he doesn’t interest me much because his private life, I think I understand who he was. In the case of Mann, it’s a constant puzzle how he managed. And, indeed, Wilde’s marriage. Wilde was a happily married man with children at one point. That’s a most interesting idea, because very soon afterwards he was not. So you are watching something change, and you are watching, I suppose, the nearest thing to historical evidence for something that’s very important, which is what the gay past was actually like.

Oh yes. I suppose that’s why in a way I’m interested in it because I am finding something that I myself experienced. If you are gay, you look in the mirror [and you think] who else is gay, what does it mean, what’s it like and what is the history. For example, if I am Irish, I can give you the full history of all our rebellions, when the English came, I can talk about the seventh century, eighth century, the history of victimhood in our lives, it’s so clear that you can even rewrite it, reinterpret it. But if you are gay, there are no 19th century ballads about being gay. I lived through that time when these things were unmentionable in Irish discourse, you didn’t read articles about anybody who was gay unless it was Oscar Wilde; you didn’t have images of contemporary people. Then you suddenly did.

Yeah, I am a failed poet – that before anything. Now I have 22 poems for all my life that maybe I would say these are okay. But I haven’t published a book of poetry yet. I probably will at some point, but really I am a failed poet. That’s what I wanted to be. The problem I have is things interest me, too many things maybe, and I take on too much, then I finish what I have to do. So I agree to write something, suddenly I have to do it. None of this is intentional. I would have been much happier at home looking out of the window, writing a few lines of poetry, then erasing it, like some serious sort of Japanese genius. But there’s too much going on for that.

Tribune News Service