Book review: where the currents of dissent flow in modern Iran

Laura Secor reported on the theocratic state for seven years and her book presents the incredible intellectual vitality and aspirations of a populace chafing against authoritarian rulers

Riverhead

by Laura Secor

In the mesmerising Children of Paradise: The Struggle for the Soul of Iran, Laura Secor captures the extraordinary intellectual and political ferment of a country where millions of people chafe under authoritarian rule.

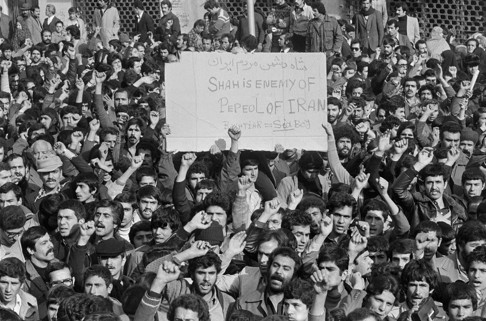

She finds that many Iranians insist on reviving questions of national identity that a quasi-theocratic Shiite Muslim regime insists were resolved with the 1979 revolution and subsequent establishment of the Islamic Republic. “To the extent that the postrevolutionary state has tried to deny the multiplicity of its origins and to suppress the engagement of its people,” the author remarks in this, her first book, “its course has followed an arc of tragedy.”

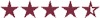

Children of Paradise recounts the history of dissent in the Islamic Republic, homing in on revolutionaries who have lost their zeal and now even question their original goals, as well as men and women who have come of age in an ostensible utopia from which they feel profoundly alienated.

In the former category, we have Abdolkarim Soroush, an Islamic philosopher who played a major role in the closure and reorientation of Iranian universities mandated by the top-down “Cultural Revolution” of the early 1980s. Soroush, advocate of an absolutist Islam, later underwent a remarkable metamorphosis. He would come to argue, in Secor’s paraphrasing, that “religious knowledge … altered and shifted – expanded and contracted – with the circumstances of history and the development of science and other fields of understanding”.

Secor, who lives in Brooklyn, covered Iran extensively for The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine and other publications between 2005 and 2012. To be sure, the author’s focus falls mostly on Tehran. And she fails to round out her narrative by surveying advocates of the regime, leaving the uninitiated with little grasp of the extent to which it enjoys popular support. Yet her coverage of dissident currents proves most informative and includes arresting portraits of well-known figures such as the late Ayatollah Ali Montazeri and unsung younger activists such as the bloggers who took the state to task for its complicity in the assassinations of dissidents. Reformists of both kinds hoped for great things with the election of Mohammad Khatami as president in 1997, but he proved timorous in the face of the hardliners.

It is worth considering the possibility that the Iranian state’s continued oppression of disaffected youth will drive more of them to outright secularism. Children of Paradise provides an account, at once comprehensive and intimate, of the varied forms of domestic opposition unintentionally engendered by the Islamic Republic. It is a substantive and deeply affecting work, and may one day boast the added historical value of providing a window into the political and intellectual arena of a pre-democratic Iran.

Tribune News Service