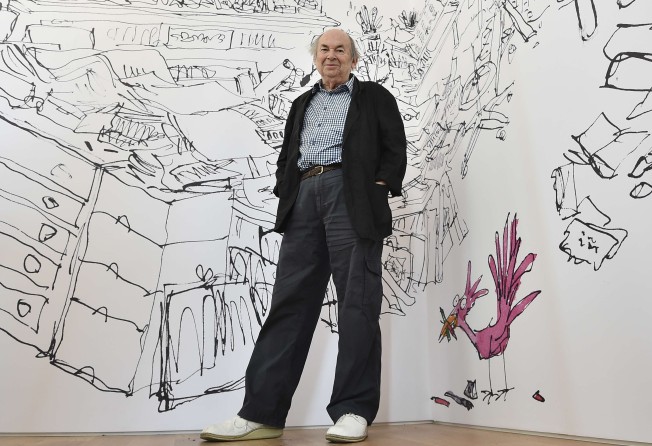

Book review: Quentin Blake’s superb grasp of the moment and the thrills of the imagination

The beloved illustrator, perhaps best known for his collaborations with Roald Dahl, has been letting his loose and lively lines take flight for more than 65 years, and a new book looks at his inimitable style and the man behind it

Quentin Blake: In the Theatre of the Imagination

by Ghislaine Kenyon

Bloomsbury Continuum

Paul Klee described drawing as taking a line for a walk, but there is nothing pedestrian about Quentin Blake’s gravity-defying figures. Think of the wretched sweet-eating infant in Roald Dahl’s Matilda, launched out of the classroom window by Miss Trunchbull, or Zagazoo’s parents, joyfully tossing their baby to one another as though he were a beach ball, or Clown, the discarded toy, hurled into the air with such vigour that he lands in the bedroom of a third-floor flat.

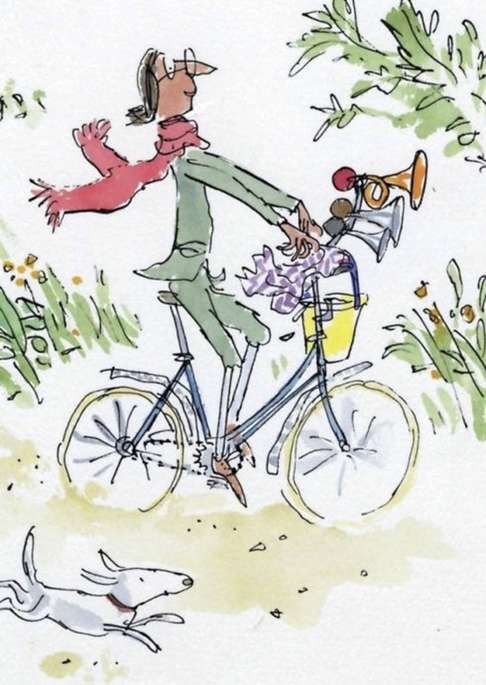

Blake’s characters are always on the move, albeit rarely walking. They run, leap, trot, dance, ride, skip, spin, swing, scoot, slide, sail, swim and, of course, fly. Sometimes they have wings (birds, and bird-like people, are everywhere in his world); at other times they are simply suspended in the sky. In one of his illustrations for the Folio Society edition of Cyrano de Bergerac’s Voyages to the Moon and the Sun, Blake shows the hero fired off like a rocket into an infinite expanse of white. In a picture to celebrate the 800th birthday of his alma mater, Cambridge University, he has a swarm of cycling students levitate like starlings into the dusk.

Blake is now 83, and his spluttery, serendipitous visual signature has been transporting readers for more than half a century. He was 16 when his first drawing was published in Punch, where the art editor pointed out that his rough sketches were better than the finished ones. This led him to develop the sense of inky spontaneity that makes us feel, as he puts it, “like something is happening now, and hasn’t finished yet”.

His rapid lines – described by Ghislaine Kenyon, who has known Blake for 18 years, as themselves “a kind of flight” – are part of the landscape of children’s literature: the dots for eyes, the retroussé noses, the flappy hands and flat, happy feet. When Blake draws, writes Kenyon, his pen takes off with a “whoosh” and the paper becomes “a page of air” through which “hordes of flying things make their way”.

It is, of course, a self-portrait – of sorts. “I’m a very detached sort of person,” he explains to Kenyon. “All the whoopee! goes into the drawings.” One of the aspects of illustration that Blake most enjoys is the way in which it lends itself to metaphor, and here Shakespeare stands in for the artist as conjurer but also for the illustrator as actor. The idea of the theatre is central to Blake’s imagination: he sees his pictures, he says, as “stagings” of narrative in which he “plays all the roles and directs and produces as well”. He compares illustration to mime, and friends say that when he draws he makes the faces of the figures appearing on the page. A former student tells Kenyon how, when Blake was once impersonating a frog trying to get out of a bucket, he became exactly like “the animation he was acting out”.

Like Blake’s illustrations, Kenyon’s writing is self-possessed and quietly brilliant. And like Lester, Blake’s much-loved dragon-dog, this book is a hard beast to categorise. It is not a biography: Blake is unattached, as Kenyon nicely puts it, to his “own story of becoming”, and his life lacks what creative writing classes call a narrative arc. There are no marriages, no children, no breakups or breakdowns; “no serious illnesses or sudden deaths; no tough menial jobs; no exotic foreign adventures or veering from any metaphorical (or literal) line that [Blake] started to draw for himself at a very young age”. There are, instead, more than 350 illustrated books, including his collaborations with Roald Dahl and the 35 stories that Blake has written and illustrated himself. Nor does his work fall into stages: Blake started good and is still good, although somewhere along the way he turned, says Kenyon, from a cartoonist into a “poet”.

The facts are few, but telling: born in 1932 in Kent, Blake was raised in a house without books. A “typical product” of the 1944 Education Act, he went from grammar school to Cambridge where he read English at Downing College during the reign of F.R. Leavis. Blake was apparently unimpressed by Leavis, who resisted interaction and gave his tutees “all the answers”, but he clearly emerged, nonetheless, a Leavisite. Not only did he become, like so many of Leavis’ students, a teacher himself (Blake trained at the Institute of Education and taught for many years at the Royal College of Art), but he has a deep understanding of how writing works. Added to which there is a lesson to his art: Leavis believed that reading makes you a better person, and Blake’s illustrations, as the graphic novelist Joann Sfar puts it, wield a “wonderful ethical power. They help me put up with my fellow human beings.”

The Guardian