Chinese-American actress Joan Chen on Hollywood, China and ‘English’, her third film as director

- Chen praises Hollywood for trying more than other national film industries to be inclusive, but says the result is sometimes more superficial than authentic

- The 57-year-old is currently wrapping up ‘English’, set in China, and says that her home country’s film industry is a ‘great market now’

It must be fun being Joan Chen in this day and age.

Nearly three decades after establishing herself as a leading Chinese-American star, with projects including Bernardo Bertolucci’s Oscar-winning epic The Last Emperor and David Lynch’s cult television series Twin Peaks, she is finally seeing diversity and representation become the talk of Hollywood – talk that partly fuelled the success of Crazy Rich Asians in the US and which is giving hope to aspiring Asian talent everywhere.

It is slightly less than four decades after she was named best actress at the Hundred Flowers Awards – China’s equivalent of the Oscars – for her role in Youth (1977), her second film role. But the Shanghai-born, San Francisco-based Chen is still finding opportunities to blossom in China at a time when even Hollywood veterans are tempted there by big bucks.

The 57-year-old actress and director is currently wrapping up her third directing effort, a Chinese production named English. “I’m very fortunate that it isn’t hard for me to come back [and work in China]. I have the best of both worlds,” she tells the South China Morning Post in Hong Kong this month, where she served as jury president for the 13th Asian Film Awards.

Though she feels opportunities for Asians are still limited in Hollywood, she acknowledges that it has improved – to a degree.

“I think Hollywood is, by far, the most conscious of any other national industry to try to be inclusive. But sometimes it’s superficial. Sometimes it’s a matter of making seven action heroes into seven different colours. It’s not about truthful experiences or authentic experiences,” she says.

She concedes that “even the superficial [improvement] is welcome”, although it soon becomes obvious that she doesn’t necessarily want to be a part of it.

“I actually believe that political correctness is detrimental to art. Hollywood is swinging back and forth because, eventually, each race, each individual will tell their experiences. [But art] has to come from that only place art can come from. It’s not about adding different races into the pot. It’s about an authentic experience.

“So that’s how I see it: I wouldn’t want to be that symbolic colour. [When] the character’s behaviour has nothing to do with my roots or my experiences, it doesn’t really mean much.”

The 2004 romantic comedy Saving Face, in which Chen plays a single mother, is widely regarded as an authentic representation of Asian-Americans. Some would argue, perhaps less persuasively, that last year’s Crazy Rich Asians was another significant step in that direction.

“This whole thing about the crazy rich was so entertainingly expressed and well told, and [had] just enough exoticism for white America. It was just a great film,” Chen says.

Asked if she believes the two planned sequels to Crazy Rich Asians will help Asian-American representation in the long run, she offers a convoluted answer that sounds a little like a diplomatic “no”.

“I think talents are talents,” she says. “[If] you have the talent, you have the drive, nothing can stop you. Whether or not it’s a political movement – that really shouldn’t mean anything to an artist. It’s completely meaningless. You have the drive, you need to express [yourself], you have something to say, and then you will say it. And there is nothing to stop you, whatever race you are.”

Amid talk of diversity gradually coming to Hollywood, Chen accepts that she is a role model for Asian actors who are finding their way. But more talk of diversity doesn’t mean things will become easier for such actors, she cautions.

“Nothing is easy. When a white actor wants to break out, it’s not easy. [For] a Chinese-American actor, it’s probably even a little less easy – because most of the writers, they do not know your experience. And so really, it’s a matter of writing your own story. You know, Crazy Rich Asians was written by a Singaporean.”

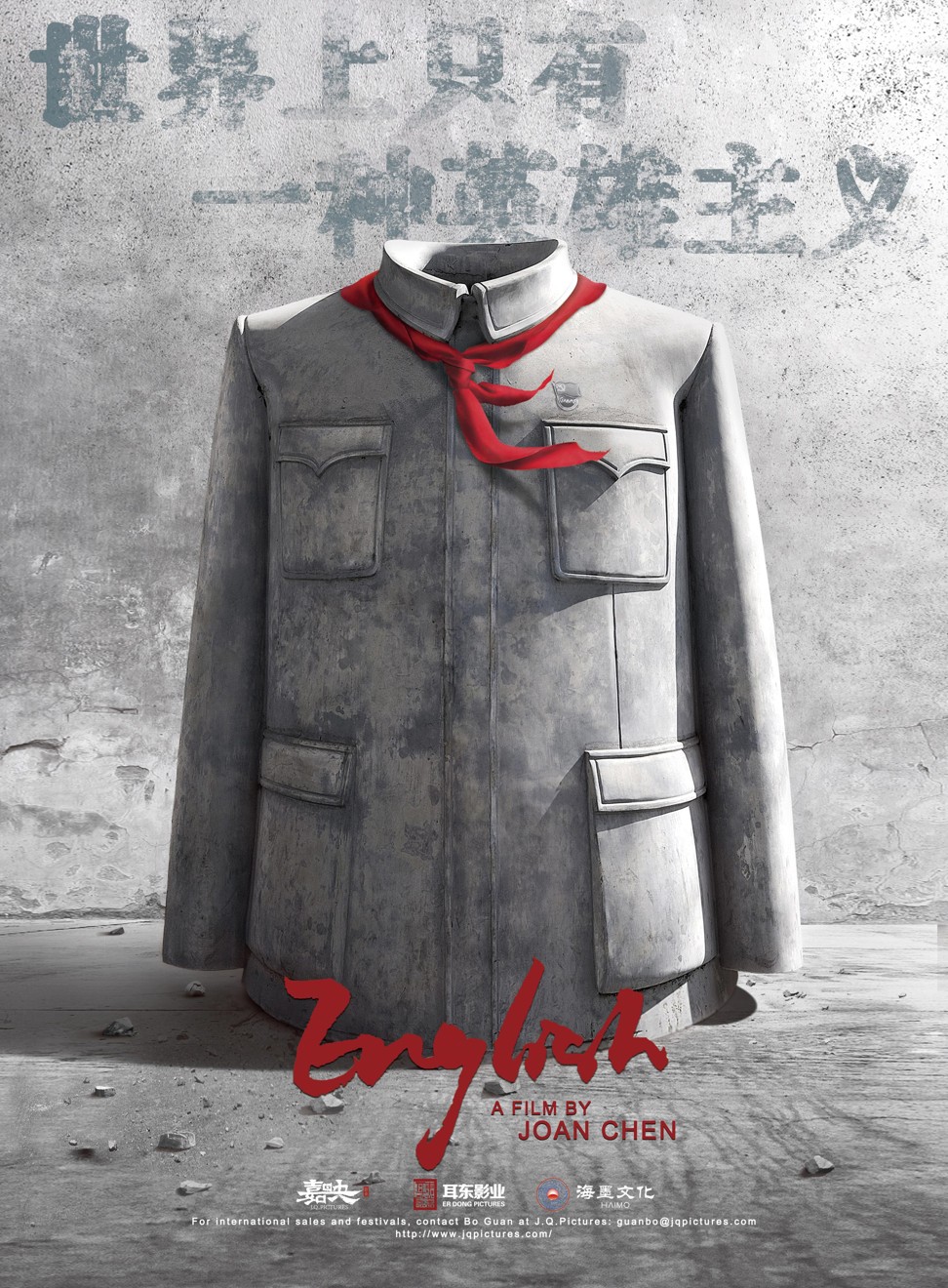

With the upcoming English, Chen’s third feature as a director after 1998’s Xiu Xiu: The Sent Down Girl and 2000’s Autumn in New York, she returns to her love of storytelling by adapting another novel she admires.

“Directing means that I get to have the most wonderful toolbox ever to help me construct a story, and to transport audiences to my world,” she says.

I just told the story the best I could; I didn’t think about any political implication. It was not about the Cultural Revolution per se. It was just set during the ’70s

In English, that world is China during the Cultural Revolution. Like many of her contemporaries, Chen can’t help but revisit that past in her films because of how closely intertwined it was with her own coming-of-age experience. Chen’s directorial debut Xiu Xiu: The Sent Down Girl was also set in the period, and won in every major category at the prestigious Golden Horse Awards in Taiwan that year.

“I have indelible memories of the era – and of the very fact when I first began to learn English, of what it meant to us,” says Chen, who studied at the Shanghai Foreign Language School as a teenager and spent much of her earnings on English coaching in her early years in the US.

English is set in the Xinjiang region of northwest China and is loosely based on Chinese author Wang Gang’s novel of the same name. It revolves around the lives of several local children and an English teacher from Shanghai as they contemplate individualism together amid the prevailing absurd social conditions. The film’s lead actors include Wang Zhiwen, Yuan Quan and Huo Siyan.

“It was a very different era, with very limited information outside of our little circle,” Chen says. “In the film, the children didn’t really even understand what English is; they didn’t think that there are these other languages. It just opened a window to the unknown, to the mysterious, to the far away, and it just captured my characters’ imagination.

“Of course it’s not all just about studying English; it’s about the English teacher, about the era, about what adults were like in our eyes when we were young.”

The Cultural Revolution is still a sensitive subject with China’s censors – just last month, Zhang Yimou’s One Second was withdrawn from the Berlin film festival’s competition. Chen also has first-hand experience with the issue from when she made Xiu Xiu: The Sent Down Girl, which she shot in Tibet without a permit. Given this, is she concerned by the potential obstacles facing English?

“I just told the story the best I could; I didn’t think about any political implication,” she says. “It was not about the Cultural Revolution per se. It was just set during the ’70s … I would never be able to guess what the censorship would like or not like, and I don’t even attempt to guess.”

Censorship aside, Chen admits that China “is a great market now” and is happy to be a part of it. For someone who left the country as a young adult to study in the US, became an international star there, and then saw her home country’s industry rival Hollywood as a leading destination for filmmaking talent, she is predictably philosophical when it comes to observations about China.

“The Chinese film industry has really grown leaps and bounds in the past 20 years, which is fantastic,” she says. “The young audiences are back in the theatres, which is also fantastic. In the meantime, are we making better films? Are we making better films than the ’80s?”

Asked if that is a rhetorical question, Chen bursts into laughter. “It’s the same thing that I want from all movies: it’s really diversity, the type of myriad humanities, the breadth and depth of who we are, authentically, truthfully – this is what I want to see on the screen.”

Apart from putting the finishing touches on English, Chen has been playing a range of smaller roles – in projects such as Tonight at Noon, Eve and Tigertail, a Netflix film co-starring John Cho – that she describes as “just cameos for friends”. “It’s really nothing to talk about. I mean, they are short jobs that I don’t need to [spend too much time on].”

Before she finds her next big part, which she admits to “always” looking out for, Chen is putting her family first. “If I get offered to do a TV series, like 60 episodes, to be shot in Hengdian, a costume drama and stuff, I would never do that, because that’s too big a chunk of my life,” she says, casually omitting the fact that she played a supporting role in the 2018 Chinese TV series Ruyi’s Royal Love in the Palace.

Acting in small doses, on the other hand, allows Chen to “practise and not get too rusty”, without taking too much away from her personal life.

“Sometimes you need to preserve your energy and use your time to think worthy thoughts and to search for worthy projects,” she says.

“And these [upcoming films] that you have mentioned are little trysts. You know, you’ve got to practise sometime. You can’t [expect to do nothing and] say, ‘OK, I’ll wait for 20 years, and finally that [big] part comes, and I’ll still know how to do it.’”

Want more articles like this? Follow SCMP Film on Facebook