Former Vietnamese refugees in Hong Kong stuck in cycle of hopelessness under a bridge in Kowloon

They left Vietnam seeking a better life but, after years in detention camps, drifted into poverty, drug dependency and crime. Jobless, homeless and unable to secure permanent residency, they are trapped in limbo on the city’s streets

Bui Quang Hiep fled North Vietnam for a better life in Hong Kong, only to end up jobless and homeless. With 10 convictions for petty crimes, Hiep has been living under a road bridge near the jade and stone market in the Sham Shui Po district of Kowloon for five years. Most of his convictions were drug-related. The 45-year-old says he was introduced to heroin by people he met under the bridge.

“Sometimes, I lose consciousness after taking drugs and wake up in a hospital,” he says.

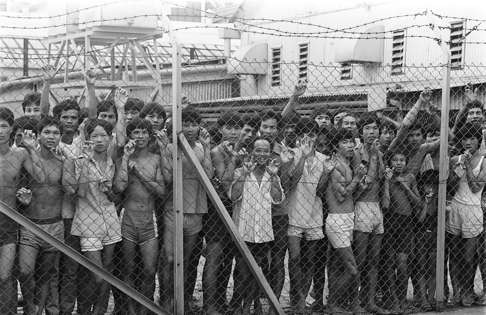

Hiep, who arrived by boat at the age of 20 in 1986, was one of more than 200,000 refugees who reached Hong Kong after fleeing communism and poverty and lived in a total of 40 camps from 1975 to 2000.

Some 140,000 were eventually settled overseas, while 70,000 were repatriated. With no one to take them, the remaining detainees, numbering more than 1,000, were issued Hong Kong identity cards.

Hiep was issued an ID card in 1994 after he left a refugee camp in West Kowloon and has not left the city since. He cannot become a permanent resident because of his criminal convictions, so is unable to apply for public housing.

Timothy Lam Kwok-cheung, a priest who has visited the homeless in Sham Shui Po for four years, says dozens of Vietnamese live under the bridge and many are in a similar situation.

“They cannot go back to Vietnam because the government does not acknowledge their identity, even though they were born in Vietnam. They must have a clean record for seven years to gain Hong Kong permanent residency. Once you break the law, the waiting period starts all over again,” he says.

“It’s about survival. They need to eat, so they might sell illegal goods such as smuggled cigarettes, or steal. It’s normal for some former refugees to have 30 to 40 convictions.”

Lam says he has helped with funeral arrangements for six former refugees.

“Their remains were left with me. When I know of people going back to Vietnam, I ask them to help take the remains back to their families. But some families have even refused to take the ashes because they’re too poor to afford a proper burial.”

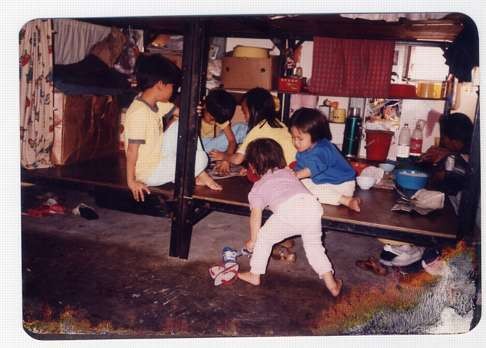

Drug abuse, petty crime, unemployment and imprisonment are common among the former refugees, who are often scarred by their experience in the packed camps. Many left the war-torn country for a perilous sea journey on rickety boats, only to be confined for years.

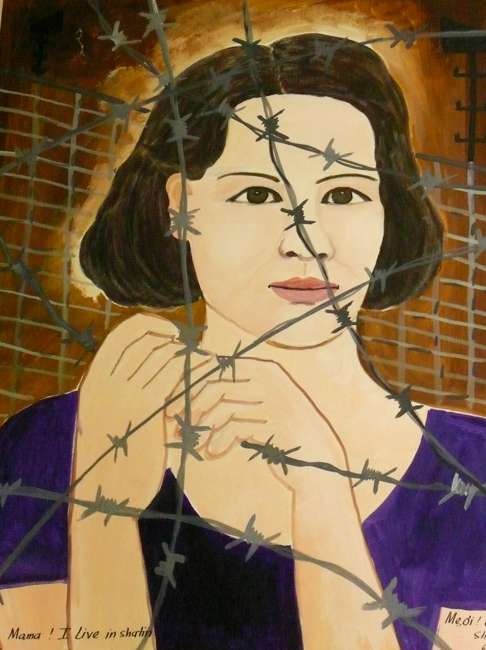

A 2014 book by Sophia Law Suk-mun, associate professor of visual studies at Lingnan University, reveals what life was like in the camps. To produce The Invisible Citizens of Hong Kong, Law interviewed seven former detainees and studied others’ paintings.

Law’s area of research is art and trauma, and the more than 200 paintings she found express anger and desperation, she says. “They found that surviving in the camps was even more difficult [than staying in Vietnam].”

Five of the works, she discovered, were painted by the same person, who later committed suicide in a camp.

“Most of the paintings are not signed; they just have numbers. They didn’t have an identity inside, just a number.”

Many former inmates don’t want to talk about their painful past, she says. “They lived in the camps for years doing nothing but waiting. It’s not surprising that some would go crazy and others commit crimes in the camps.”

Law also found the diary of a 16-year-old girl who had travelled alone to Hong Kong. “If she hadn’t sought out a triad protector, she would be raped every night inside the camp.”

Hiep stayed in two camps over four years and described the days as interminable boredom.

“It was a miserable existence. Besides eating three meals a day, there was nothing to do.”

With waves of boatpeople washing up in Hong Kong, the colonial government began to separate political from economic refugees in 1988, forcibly repatriating the latter a year later. Fearing their return, a large-scale riot involving 1,000 detainees broke out in 1996 in the Whitehead camp in Wu Kai Sha, which housed 8,000 boatpeople.

According to Law, the refugees’ plight was initially met with sympathy in Hong Kong, but that changed as the years wore on.

“I read all the newspaper coverage from those 25 years. In the beginning … the government was urged to build a telegraph centre next to camps so the inmates could contact their relatives back in Vietnam. People took sweets and toys to the camps, which were open at the beginning. Detainees went out to work and came back at night. But later, the media reported that the Vietnamese stole jobs from locals.

“Later, the camps were built further and further away, like in Chi Ma Wan on Lantau Island. The photos of camps in newspapers were all shot from afar. Portraying the Vietnamese as aliens born to be violent, the media focused on riots, deaths, tear gas and so on.”

Vu Thanh Thuy, a recent arrival in Hong Kong, was among those living under the Sham Shui Po bridge last year. One of 7,000 Vietnamese babies born in Hong Kong camps, she came back to the city after being conned into believing she was eligible for an identity card by birthright and a chance to settle in another country.

“I paid HK$30,000 to people to bring me and my daughter to Hong Kong, hoping I could go to Canada or America. Half of the money was paid by my family and I borrowed the remaining half,” the divorcee says. Her parents fled Vietnam in 1988 and returned in 1991, when Thuy was a year old.

Upon arriving in Hong Kong, Thuy was devastated to learn she had been the victim of a scam. She has to renew her temporary identity document every month, and must wait years for the government to assess her refugee status, during which time she cannot work. Thuy receives HK$2,400 in food vouchers a month from the International Social Service.

“When I first came here, I lived under the Sham Shui Po bridge for two months. Later, the church and priest [Lam] helped me pay for a small flat in Shau Kei Wan,” she says.

“I regret coming here because I can’t work. I ran a clothing stall back in Vietnam. But luckily my daughter is allowed to get an education here. She’s in the second year of kindergarten now. As for our future, I’ll just see how it goes.”

The picture is not all bleak for Vietnamese refugees who stayed on in Hong Kong. Tran Trong Manh, who left Vietnam in 1983 at the age of six, took part in a riot at the Pillar Point camp in Tuen Mun in 1999. He was jailed for three months for his involvement.

“After hundreds of south Vietnamese moved into the camp, [also escaping poverty] fights broke out between the north and south Vietnamese. The two sides were involved in a turf war.”

Pillar Point camp was the last one to close, in 2000. When the last batch of inmates resisted and tried to stay put, the government terminated water and electricity supplies, forcing them to vacate the quarters.

I will go back to Vietnam when my daughter is a bit older. My hometown, Hai Phong in North Vietnam, is very different from when I left three decades ago

After leaving the camp, Manh, 37, did odd jobs including selling smuggled cigarettes and pirated discs. In 2008, he was sentenced to two years in prison after arranging for another Vietnamese man to illegally enter Hong Kong to attack Ma Chiu-sing. Ma had been convicted in 2007 of criminal intimidation over acts intended to damage the reputation of Oriental Daily News. After his release, Manh got married in 2011 and his wife gave birth to a daughter. Reticent about his past, he says he is now a trader.

“I will go back to Vietnam when my daughter is a bit older. My hometown, Hai Phong in northern Vietnam, is very different from when I left three decades ago. I hopped on a boat to Hong Kong on the advice of my father, and went back to Vietnam for the first time four years ago to pay respects at my father’s grave.”