Should dads be in the delivery room? We look at the pros and cons

Many men say seeing their partner give birth is one of the most momentous events in their life, but doctors say the father’s presence is not always helpful; some feel out of their depth, but others provide positive energy during labour

A number of Chinese traditions persist around pregnancy and delivery. There is the practice of “sitting the month” – a centuries-old custom that prohibits new mothers from eating certain foods or leaving the house. Another ritual permitted a father’s involvement in a baby’s first bath but excluded him from being present during labour. And – as unfashionable as the notion is now – there is the banning of dads from labour wards.

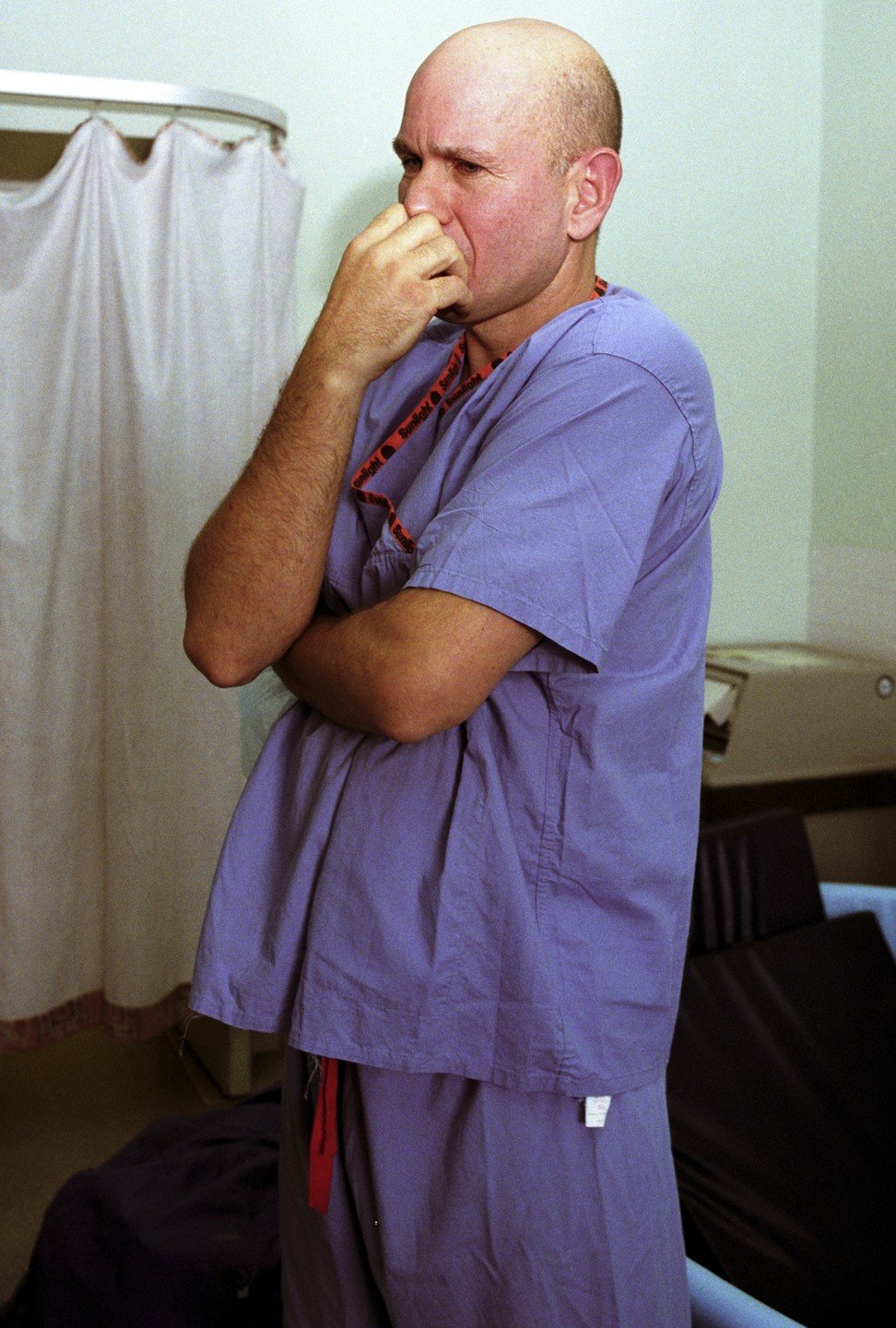

Some fathers attend their child’s delivery because they feel they “ought” to be there, not because they want to be there. They may not enjoy it. Not because they are squeamish, but out of a feeling that “here was the person I loved most in the world undergoing this horrendous pain and distress and there was absolutely nothing I could do to alleviate it for her”.

In Britain, at least, it’s estimated that more than 90 per cent of fathers attend births. Most claim the experience is among the most precious of their lives, but are they telling the truth?

In 1960 – when the rate was closer to 15 per cent – a London doctor interviewed fathers and their partners post-delivery. He asked the dads if they had been happy witnesses to the birth of their children. Without exception they collectively responded yes.

The doctor, George Davidson, then spoke to each father alone, assuring them that their responses were confidential. This time most of the men said that although the birth was an extraordinary experience, it was one they could have lived without. Many felt it had done little to improve their relationship with their wives, and some admitted that the image of a labouring partner intruded on what had been a healthy sex life.

Davidson’s findings were largely ignored and fathers were increasingly found in delivery suites rather than skulking in hospital corridors. But in the late 1990s Dr Michel Odent, the French obstetrician who pioneered the water birth, did something even more fantastical than advocating babies be born in a paddling pool: he was conspicuous by his absence when his own wife gave birth.

Having interviewed hundreds of couples, Odent proffered that the father’s presence was not always helpful during delivery.

A father, distressed at seeing his partner in pain, was likely to try to comfort her by talking to her, he noted, but attempts at conversation forced the woman to respond with the rational part of her brain, which is enormously distracting for someone who needs to be in touch with her primitive self. In so doing, Odent said, men hindered labour, possibly contributing to higher rates of Caesarean-section births.

Liz Purnell-Webb, founder of Hong Kong-based pregnancy and birthing specialists A Mother’s Touch, says she is “a great believer that babies should be born in the way that they were conceived”, providing they were conceived in a positive environment, “with intimacy and love”.

“Research suggests that a baby coming into this world benefits not only from hearing their parents’ voices but also as a result of the parents’ microbiome,” Purnell-Webb says. “If a mother has had a C section, a father is present to deliver important skin-to-skin contact directly after birth.”

“Fathers’ empowerment, intimacy for the couple, closer bonding for parents and baby, and baby benefiting from the microbiome at birth” are all valuable reasons for dads to be present, she says.

She agrees, though, that many fathers feel out of their depth and don’t understand what they can do to support their partner.

“It’s up to the birthing community to offer practical support to dads leading up to – and during – their baby’s birth; often those who still feel some hesitation find a doula,” she says (doula being ancient Greek for “handmaiden”). This can help overcome any fears they may have.

Odent advocated the services of doulas – women who have had babies themselves and are hired as birthing partners, and who can champion a labouring mother from the position of informed experience.

It’s up to the birthing community to offer practical support to dads leading up to and during – their baby’s birth

Kathy Kitzis lived in Hong Kong for 14 years, delivered all three of her children in the city and worked as a doula and a teacher for childbirth education programme Calmbirth for eight years. She says: “I am a big advocate of having the best people in the room, people that are going to bring positive energy.” That could be the child’s father, the labouring mother’s own mum, or a doula.

Every woman is different and every situation unique, she adds. “It’s not a one-size-fits-all. I have been at births where I have done everything I could to encourage a mum, and it has taken a quiet word in her ear from her husband to encourage her.

“I have also been at births where the husband really doesn’t know how to help,” and is reduced to a “hindrance”.

Kitzis absolutely advocates involvement of both parents pre-labour. “I strongly believe both mother and father should prepare for labour, as they both have different roles and it is very important that they both understand how labour works.”

She agrees there is enormous pressure on fathers today to be “this amazing birth partner”, but worries that “it’s not in a man’s DNA to be a good birth support partner; they like to ‘fix’ problems, when very often normal labour is not about fixing something but about being patient and supporting and bearing witness to a woman’s efforts”.

Still, Kitzis says: “I have seen such amazing connection between the mother and the father during labour and birth. I think it is sad if dads don’t get to witness how amazing birth can be, and they always have a new-found respect for their wife, seeing what she has gone through.”

Purnell-Webb agrees. “I have had many dads who, if actively involved, have really felt that primal protective instinct come to the forefront, and would not have missed their baby’s birth for anything.”

Australian writer David Vernon’s 2006 book Men at Birth includes the experiences of hundreds of fathers who attended their children’s delivery. While many of the men Vernon interviewed ranked witnessing their child’s birth among the most momentous events of their life, a number did not.

“Women in labour have the benefit of hormones such as oxytocin and endorphins surging through their body, and thus their perception of pain is vastly different to their partner’s. To a man [who has never heard a woman in labour before] the birth noises can sound like extreme agony, and this understandably makes the man anxious or frightened,” he writes.

A plethora of studies have been conducted on the value or otherwise of fathers being present during delivery. Several corroborate the ideas of Odent and Vernon: if men understand pain during childbirth, their women may have shorter, less complicated labours, and a stressed birth partner is counterproductive.

Mothers need to heed the results of another study: the attendance of fathers at birth is not correlated with higher levels of involvement in, say, nappy changing.

And therein lies the crux of all this – there isn’t a right way to do things, only a right way for you. And it’s imperative to remember that being absent at their child’s birth does not make a father a less present parent.