How pioneering biomedical engineer helped Hong Kong's disabled

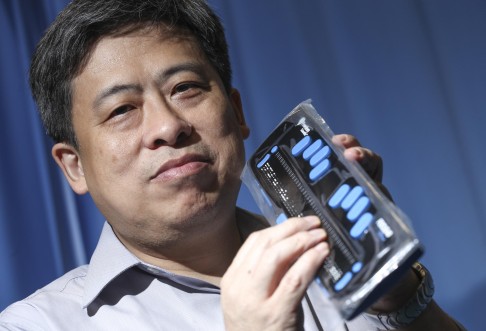

Dr Eric Tam Wing-cheung has helped improve quality of life for the city's disabled for more than two decades, writes Bernice Chan

Seemingly simple tasks such as sending e-mails or just moving around the house can be enormous hurdles for people with disabilities. But thanks to people like Dr Eric Tam Wing-cheung, their lives are being made easier.

In his 25-year career as a biomedical engineer, Tam has helped many people, among them Tsang Tsz-kwan, a blind and hearing-impaired student who made headlines in July by achieving excellent results in the Diploma of Secondary Education exams (5* and above in five subjects and a 4 in the sixth).

"I first met Tsang two years ago and she was already talking about [taking] the exam," say Tam, an associate professor at Polytechnic University and director of its Jockey Club Rehabilitation Engineering Centre. "She is very ambitious and determined. She has never doubted herself."

After completing primary education in a school for the visually impaired, Tsang, 20, attended Ying Wa Girls' School, a conventional high school. Tam first got involved in Tsang's life when his team modified a conventional computer keyboard by adding small hollowed out cubes on top of the keys that allowed her to better position her fingers.

"I don't know how much she uses it, but I saw her before the exam and she showed me how she used it, so I know she was practising," he says.

Biomedical engineering was a largely unknown field in Hong Kong when Tam returned from his studies in Canada in 1986.

After earning a degree in engineering physics at McMaster University, he switched to the University of Saskatchewan to pursue his interest in biomedical engineering. "I have a sister who is a nurse and uncles who are medical doctors, so I knew a bit about the medical field but didn't think I had what it took to be a doctor," Tam says modestly.

There were initially no jobs where he could apply his expertise, so Tam took part-time teaching assignments in high schools and bided his time. Then an opening came up at PolyU's Industrial Centre, which spun off the rehabilitation unit as a multidisciplinary venture to help disabled people. It has proved to be enormously satisfying and eye-opening work.

"In Canada, I learned theory, but here I learned practical things," Tam says. "People have their individual disabilities so you identify their needs and see how you can help them. There are custom-made things for individuals and then training devices that are used in hospitals for rehab."

Many patients at the university's rehabilitation clinic are children with conditions such as spinal muscular dystrophy and cerebral palsy and cannot sit properly. Tam's team often works with specialists at Prince of Wales Hospital and Chinese University to modify wheelchairs to help keep the children upright, delaying skeletal deformity and allowing their hearts and lungs to develop more normally. "It's important to me as a teacher in this field to go to the front line to understand the needs of patients. There are other professionals helping these people, so we work with them to bring together information and knowledge," he says.

The work of Tam and his team led PolyU to launch a biomedical engineering programme in 2000, the first such course in Hong Kong. Since then, Hong Kong, Chinese and City universities have started their own programmes.

"When they compare what a starting nurse can make, about HK$20,000, or a physiotherapist, engineers have a relatively low salary," he says. "But they need to focus on the longer term. If they get a higher education they can earn up to HK$60,000 to HK$70,000." Tam tries to encourage his students to go into manufacturing medical devices, which is an area he believes has a lot of potential. But this usually requires working on the mainland as "even devices bought from North America [are] made in China," he says - and many are reluctant to adapt.

Five years ago the rehabilitation centre began working on assistive technology, bringing together doctors, speech and occupational therapists and other specialists to work out ways that mentally retarded and physically disabled people could use technology to express themselves. That is how he met Tsang.

Tam has had other success stories, including a boy with spinal muscular atrophy he met 14 years ago. He is now 18 and has completed high school. Tam's experience with quadriplegic Tang Siu-pun has taught him that specialists like him must be sensitive to individual needs when they try to help. Tang, better known as Ah Bun, issued an open request to be allowed to die in 2003 after spending 12 years confined to a hospital bed after being paralysis in a gymnastics accident. Tam's team, which was trying to devise ways to give Tang better computer access when he made his plea, found their patient took longer than they expected to adapt to his new communication tool.

"We can't just give them new technology and think that because it's better they'll use it right away," says Tam. "Sometimes it takes a while for them to accept the reality of their situation, particularly when they are newly injured. We might be aggressive and try to do as much as we can as fast as possible, but it depends on if they are keen or not and if they can accept their situation," says Tam.

Some parents come to the centre expecting their child to be given a communication device, he says, but often the hurdle is a lack of communication between the parents and the child.

"They don't understand what technology can do. If they give us more feedback then we can help them. Then there is the other extreme where we get a lot of demands, but that helps us better understand what the person needs."

For a person who didn't have the strength or flexibility to move the joystick on a motorised wheelchair, for instance, Tam and his team developed a touch pad that allowed the user to control the chair with light touches and slight movement.

His teaching duties and projects aside, Tam's challenge now is ensuring the rehabilitation centre's financial sustainability. It charges HK$800 for an initial consultation fee, with further charges depending on the device or service sought. The problem is this is a figure prospective clients may balk at, even though government subsidies could cover much of the costs after the initial visit.

As there are no hospitals employing biomedical engineers dedicated to helping those with special needs, the centre is the only one of its kind in Hong Kong. From modifying wheelchairs to creating other gadgets to make the disabled more independent, the centre is not a commercial operation and so government funding could enable it to help even more people have better control over their bodies and lives.