The three issues at heart of the outrage over history exam question in Hong Kong about Japan and China

- Anger over the question about Japan’s impact on China is threefold: that it was ever asked, the way it was worded, and that politicians would meddle with exams

- A teacher not involved with DSE says submissions about the exam should have been written down, made public, and those responsible allowed to mount a defence

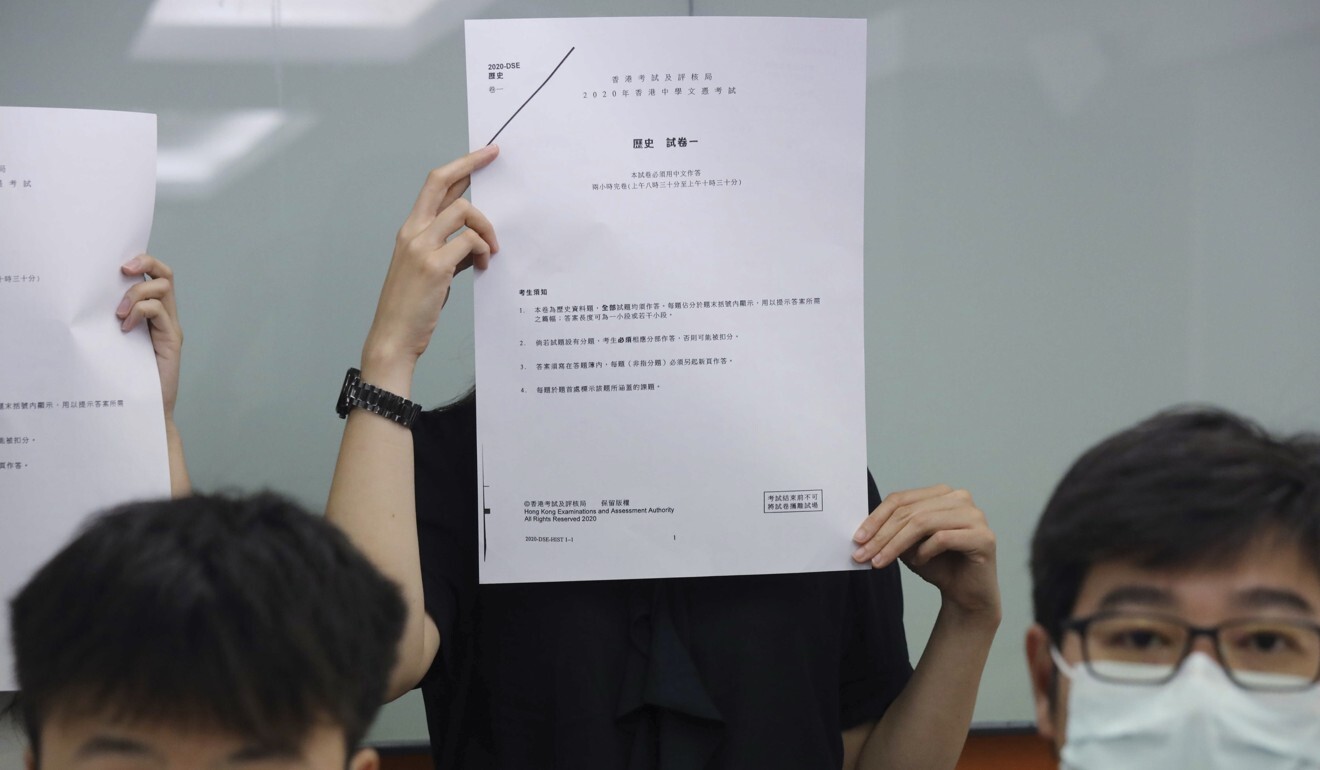

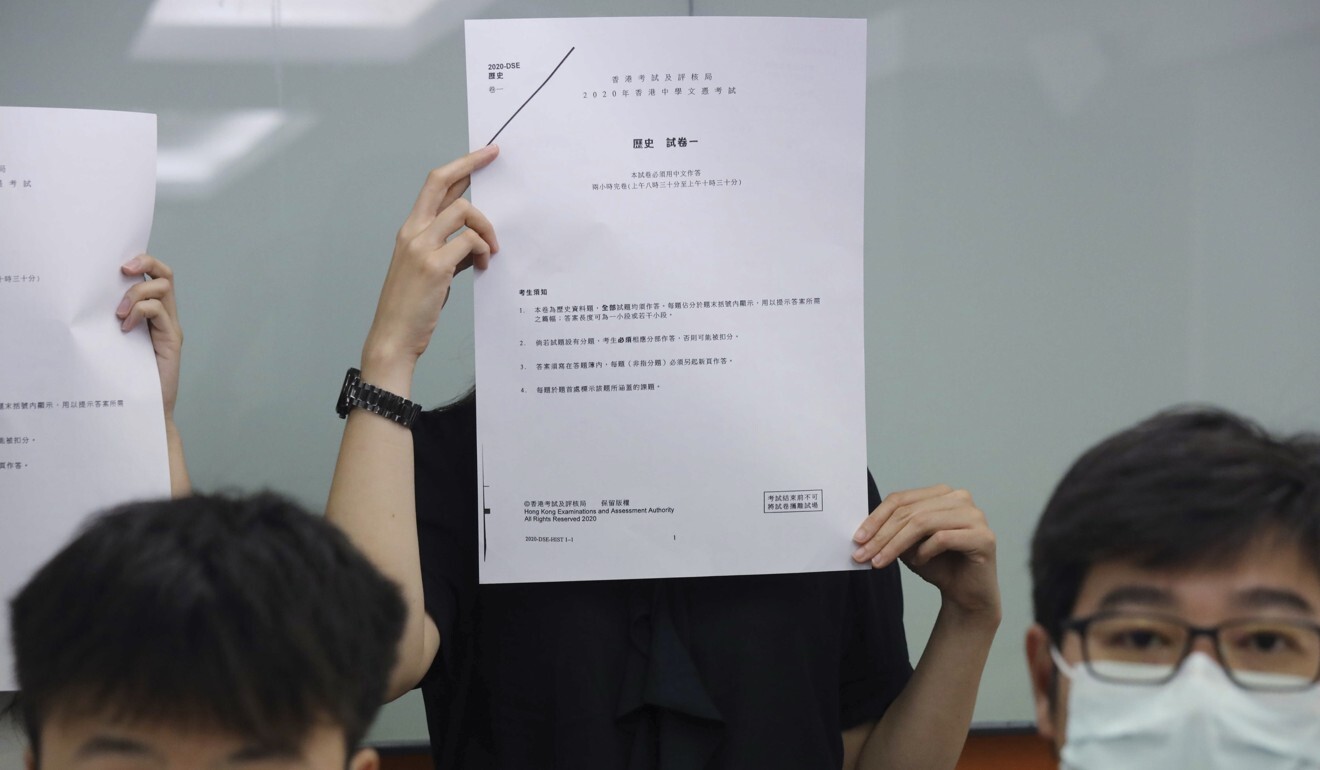

A question on a history paper of the Hong Kong university entrance exam, the Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education (HKDSE), that asked students whether they agreed Japan did more good than harm to China in the period between 1900 and 1945 has engendered outrage from sections of the Hong Kong community. However, this indignation confused and confounded three separate issues.

First was the outrage that such a provocative question could be posited in the first place by the Hong Kong Examinations and Assessment Authority. On Friday the authority announced the question had been scrapped and a predicted score would be given to affected candidates based on their answers to other questions on the paper.

“No one would imagine a comparable question in Europe: ‘Do you agree that Germany did more good than harm in France (or Poland, for example) between 1900 and 1945?’,” says history teacher Robert Jones (not his real name). “Asking such a question would be seen as odd or embarrassing, to say the least, and would actually be perceived as very insulting.”

Jones believes asking students to consider the positive aspects of a foreign invasion and occupation is ethically wrong, not just for the fact that 10.2 million Chinese citizens lost their lives during Japan’s occupation, but also because it seems some in Hong Kong are questioning the possible benefits of a war, when war should not even be the last resort but, in 2020, should be considered an abject failure.

“We study history not to study wars. We study it with the dream of ending wars,” says Jones.

Second, there was offence at the structure of the question because, through its wording, it can be read as a leading question.

Both sides in this debate agree on one important point: that the teaching of history matters because it helps us define and understand who we are

“There is this assumption of Japan doing more good than harm,” Jones says. “Of course, one can disagree, as the question starts with ‘do you agree’. However, the sources provided to students were not balanced and we can observe that both documents supported the view implied in the essay question, that yes, the Japanese did more good than harm in China between 1900 and 1945.”

Another teacher has been quoted as saying: “By presenting a ‘thought-provoking’ statement, examiners aimed to stimulate critical thinking in students.”

However, for critical thinking, students must weigh evidence from multiple sources and find information to explain incongruities. When using more than one primary source, the items should present different perspectives. Providing only sources that support the assertion in the question is suspect. How would that enable students to compare and contrast points of view?

The now-infamous question was part of paper one, answers to which determine 60 per cent of the total history mark. The content of the test questions is based on primary sources of historical information.

The source documents supplied to the students included excerpts adapted from articles and letters from the early 20th century, before Japan’s invasion of China.

“Such documents should be rich and multifaceted, and students should be invited to consider not only the content but the type of document, the source, the date, the original purpose of the document and the context in which it was created,” says William Whitehurst, who teaches history at the French International School in Hong Kong.

Students should be asked to construct a well-reasoned argument based on historical evidence that also recognises other possible ways the evidence might be interpreted.

Interestingly, the History Department Public Examination Evaluation Objective is to assess candidates’ ability to “interpret and evaluate historical evidence, compare different historical materials and draw conclusions and clearly discriminate against bias”.

Some students have claimed in media interviews that they didn’t find the question outrageous. “The question itself doesn’t have any problem, because it’s just answering from the benefits or pros and cons, which is a common type of question you see in HKDSE history questions,” one student said.

Can the students’ lack of outrage be ascribed to poorly developed critical-thinking skills or simply to anti-China sentiments? No similarly leading questions can be seen in a quick search of past HKDSE history exam papers, nor could bias be found in the supplied support documents for past questions.

Third, the outrage of education sector lawmaker Ip Kin-yuen and other like-minded individuals who believe exam questions cannot be criticised needs to be addressed.

“If the [HKEAA} council is going to say that this kind of question is not allowed, it will have a far-reaching impact on … the future of assessment systems in Hong Kong,” Ip was quoted as saying before Friday's decision.

What will have a far-reaching impact on future assessments is failing to ask who develops these questions and who decides which of them are selected for examinations.

History teacher Whitehurst is extremely curious to know how students responded to the Japanese occupation question and he feels strongly there should have been a fair and transparent process in place to deal with the disapproval.

Allegations should have been specific, summarised in writing, and available for Hong Kong teachers and the general public to scrutinise, and those responsible should have had the right to defend themselves, he says. Putting in place procedures that address future infractions should be the key concern here.

“I think it is worth noting that both sides in this debate agree on one important point: that the teaching of history matters because it helps us define and understand who we are,” Whitehurst concludes.

We should build on that point to encourage social communication and dialogue on education policy.

Anjali Hazari is a retired international-school biology educator who has taught for three decades in Hong Kong and has received several accolades in her teaching career. She continues to tutor and write extensively on education policy and practice