How secrets of ancient Egyptian child’s stripy sock were unravelled using new imaging technology

The 1,800-year-old knitted sock, found in a rubbish dump from the Roman era in Egypt, was examined using a new, less destructive technique that yielded details of how it was dyed

The ancient Egyptians famously gave us paper and the pyramids, but were also early adopters of the stripy sock.

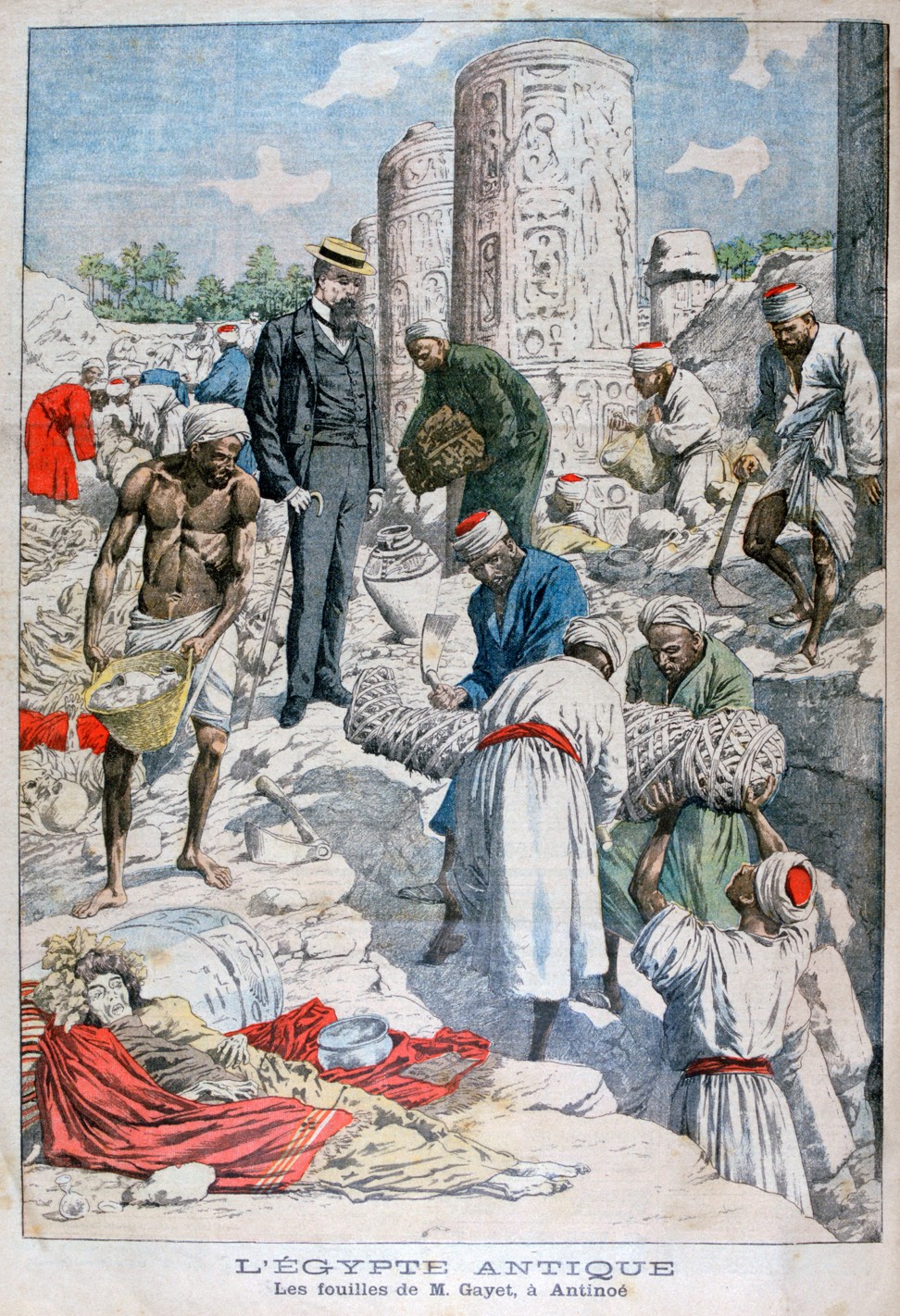

Scientists at the British Museum have developed pioneering imaging technology to discover how enterprising Egyptians used dyes on a child’s sock, recovered from a rubbish dump in ancient Antinopolis in Roman Egypt, and dating from AD300.

New multispectral imaging can establish which dyes were used – madder (red), woad (blue) and weld (yellow) – but also how people of the period used double and sequential dyeing and weaving, and twisting fibres to create myriad colours.

Crucially, the imaging is non-invasive. Previously, studying ancient textiles using radiocarbon dating and dye analysis required physical samples to be taken.

Dr Joanne Dyer, a scientist in the museum’s department of scientific research who developed the approach, said: “It was exciting to find that the different coloured stripes found on the child’s sock were created using a combination of just three natural dyes.”

The imaging process is a far cheaper, less time-consuming and less destructive way of studying ancient textiles, she said. “Previously, you would have to take a small piece of the material, from different areas. And this sock is from AD300. It’s tiny, it’s fragile, and you would have to physically destroy part of this object, whereas with both the [multispectral] imaging, and other techniques, you have a very good preliminary indication of what these could be.”

The technique, details of which are published this week in the open-access journal PLOS ONE, looks at the luminescence of different dyes and uses digital microscopy to examine fibres. It allows many more textiles to be examined, adding a rich layer of discovery to the understanding of how events in this period affected people.

“It means we can look at more, and a larger variety of, objects. We can see the relationship between more objects and different time periods,” said Dyer. “Late antiquity is a very long period, from AD200 to AD800. Within that period in Egypt there are lots of thing happening. There is the Arab conquest of Egypt, the Romans leave Egypt. These events affect the economy, trade, access to materials, which is all reflected in the technical make-up of what people were wearing and how they were making these objects.”

While socks have been around since the stone age, made from pelts or animal skins, the ancient Egyptians are thought to be responsible for the first knitted socks, styling them with one compartment for the big toe and another for the remaining four toes to use with sandals.