How natural dyes could solve fashion industry’s polluting practices, and the brands in Southeast Asia leading the way

- Plants, mushrooms, lichen, algae and more are being used to create natural dyes that don’t add to fashion’s incredibly harmful effect on the world’s water

- Natural dyes offer a charming spectrum of tones and shades, but mastering them requires a depth of knowledge and patience

The way fashion works right now is bad for the Earth. The astonishing rise of fast fashion over the last decade has created a monster; specifically, a monster that is one of the most environmentally harmful industries in the world, responsible for 10 per cent of global carbon emissions and the second-largest polluter of water worldwide after agriculture.

Every step involved in getting new clothes into the hands of consumers has its own issues, but one of the most damaging is textile production. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, textile production and dyeing consume around 1.5 trillion litres (396 billion gallons) of water annually, and are responsible for harmful textile waste and chemicals being dumped into surrounding waterways.

An example provided by the panel showed that one European textile-finishing company alone could use over 466g (1.03lb) of chemicals per kilogram of textile.

The good news is that this has not gone unnoticed. And while some have proved resistant to change, more fashion lovers and makers have been turning to slow fashion, which at its heart is the idea of independent makers eschewing the breakneck speed of the fast fashion model.

When speed and volume are no longer the driving motivation behind production, makers and designers can concentrate on creating fewer but higher quality garments, working with sustainable or repurposed textiles.

A key tenet of slow fashion is looking to local makers and supporting surrounding communities. In Southeast Asia, that has seen a return to traditional techniques that not only supports local communities, but revitalises practices that could otherwise have been forgotten. The result? Beautiful, sustainable wares with minimal environmental impact.

An area that has seen tremendous interest is natural dyes, a logical move for those worried about the environmental impact of their clothes.

While industrial-level textile dyeing may leech dangerous chemicals into freshwater streams and damage local flora, fauna and communities, small-batch natural dyeing does exactly the opposite. The success of natural dyes depends on people respecting and nurturing the environment around them, and coaxing colour out of it.

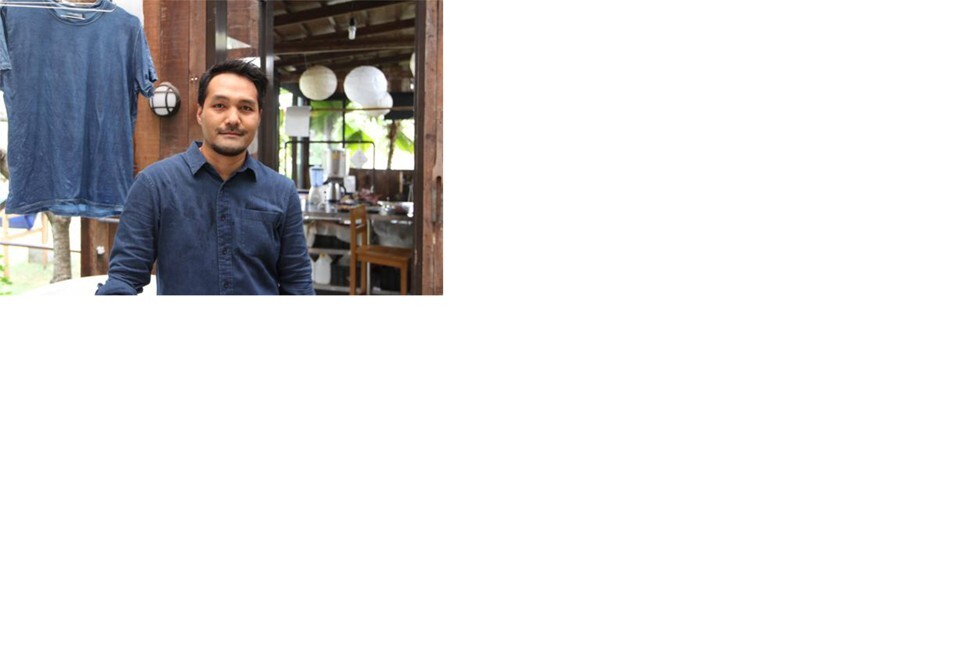

Muni Osman runs Munimalism, a dye and design studio based in Sepang, Malaysia, that produces apparel and accessories dyed with ingredients found in the Malaysian countryside. His immersion into the world of natural dyes came completely by chance.

“My first encounter with natural dyes was during an architectural project trip to Bali,” he says. “I had visited one of the spectacular bamboo villas in Green Village, which they had decorated with traditional handloom Sumba textiles, and I was immediately drawn to the colours’ rustic beauty and faded tones.

“Having previously worked as an interior designer where I was surrounded by plenty of fabrics, seeing natural dyes was a refreshing change. The colours were raw, imperfect but honest.”

The visit sparked something in Osman that sent him on a mission to learn the intricacies of natural dyes.

“The process was long and required huge commitment. It took me a few years of mastering the art, including making multiple trips to different parts of Indonesia.

“The decision to develop a brand was an organic one. And more importantly, upon learning the process, I saw it as a potential for the fashion industry to operate in a much leaner and cleaner way.”

Now Osman heads up a proudly Malaysian offering, creating cotton and bamboo apparel and accessories in an appealing rainbow of colours derived from local ingredients such as mango leaves, sappanwood, mangosteen fruit skins, rambutan skins, turmeric and coconut husks.

Each item is hand-dyed and the process is meticulously documented; buy a T-shirt and you’ll learn all about its composition, what ingredients the dye was derived from, even how many times it was dipped in said dye. Munimalism is stocked in stores and five-star resorts across Malaysia, where its wares sell out very quickly.

Of course, natural dyes are not a concept exclusive to Malaysia, or even Southeast Asia (although there is evidence that many of the most popular natural dye ingredients, like cinnamon, were imported from Malaysia over a thousand years ago). Natural dyes were, after all, the first kind of dye, before synthetic dyes became ubiquitous in the 1900s.

But where synthetic dyes are easy and often instant, natural dyes require a depth of patience and knowledge. It’s a common misconception that the colours produced by natural dyes are muted and insipid; have you ever accidentally stained a kitchen towel bright yellow with an unknowing smear of turmeric?

What natural dyes offer is a charming spectrum of tones and shades that depend on a multitude of different factors. It’s this uniqueness and individuality that has drawn in makers and brands across the world. Look at Rudy Jude’s organic, naturally dyed basics in clear tones of claret, mustard and fawns. Or Australian-Indonesian brand Rupahaus’ collection of breezy resortwear, hand-dyed and handwoven using traditional Indonesian techniques.

Someone who well understands the charm of natural dyes is Ummi Junid, the designer behind Dunia Motif, a project that champions batik and natural dye. Like Osman, Junid’s first foray into natural dyes happened by chance, while researching different forms of batik.

“The quest for the past of batik led me to discover that in the 19th century, batik was made using natural dye derived from local plants,” Junid says. “The first natural colour I’ve ever seen in my life, which made me fall in love with it, was the indigo blue dye.”

Junid subsequently travelled to Pekalongan, Indonesia and adopted her own indigo seed. “Since then, I have been growing and harvesting my indigofera tinctoria plant, growing my love for natural dye discovery step by step. Today, I can easily tell what plants and flowers produce natural colour, and guide those who are interested in producing natural dye from their garden and home kitchen.”

Junid also completed a master’s degree in textile design, focusing on natural dyes and the sustainable processes around it.

“Half of my learning process involves visiting people and listening to their experience of natural dye. I was pleased to have met natural dyers around the world – via online webinars – during the pandemic season earlier this year,” she says.

“These online meet-ups encouraged me to dive deeper into different ways of natural dye creation, such as rust dyeing, collecting colours from mushrooms [mycelium], and learning about the pigments from lichen and algae.”

Junid practises what she preaches, creating dyes from her kitchen waste, and reviving second-hand and thrift-shop purchases. She has also published a wealth of knowledge and guidance on the Dunia Motif website, where people can find how-to guides about making natural dye from their home kitchens.

Instead of waiting on the big companies to do better, she’s doing it herself.

“We are in desperate need of a whole change of fashion. Sustainable fashion can be implemented on a larger scale by looking at holistic solutions. The revolution is not going to be born from the makers. We all have to play our role. Wash our clothes differently. Repair or upcycle. Reuse or re-dye your old fabric instead of throwing it away. Consider the impact of the material they are made of. Consider the supply chain and who produced them,” she says.

“And the best thing to make fashion more sustainable is to slow down our consumption. We have all been casual about our clothes. It’s time to get dressed with intention.”