Why 700 million in China are waiting for glasses, and how to fix the problem – a Hong Kong philanthropist’s vision

A lack of eye doctors in China, particularly in rural areas, and the increasing time spent staring at phone and computer screens, has left half the population suffering from bad sight. A charity sees solutions in its experience in Rwanda

Nearly half the people in China – an estimated 720 million – have uncorrected sight problems because they cannot get eye examinations, a recent study found. Ninety per cent of them just need a pair of glasses, its authors found. It was a problem that hampered the country’s social and economic development, they concluded.

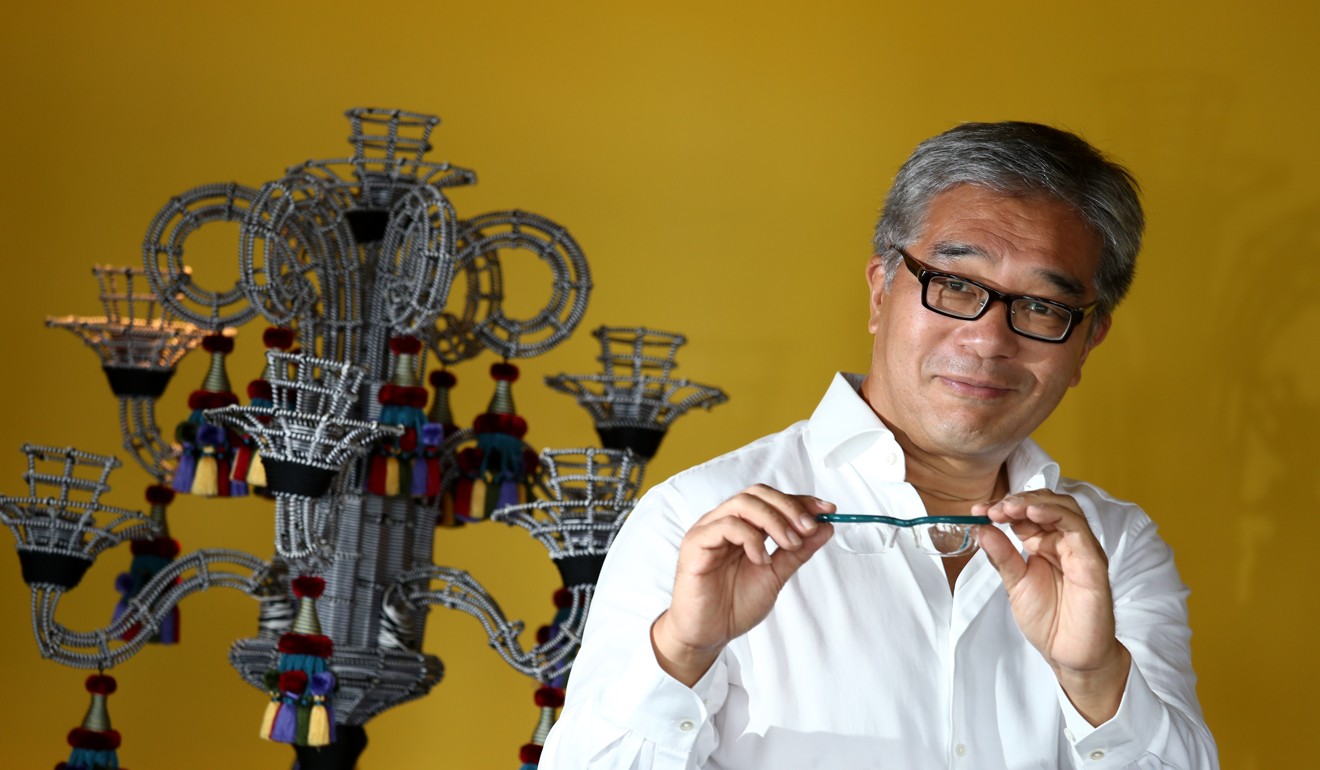

The report was released last week by Clearly, a charity founded in 2016 by Hong Kong philanthropist James Chen.

Chen says two of the biggest reasons for the large number of people with uncorrected sight problems were the lack of specialist eye doctors, particularly in rural areas, and the increasing amount of time spent staring at computer and smartphone screens.

“Poor vision is the largest unaddressed disability in China,” says Chen, who led the research. “And the solution is simple – and invented centuries ago: glasses.”

Eyesight problems affect people all over the world, but especially those in developing countries. An estimated 2.5 billion people, or a third of the world’s population, need glasses but do not have any, according to Clearly. The estimate is based on analysis of data from more than 20 studies conducted in various countries.

China accounts for the biggest share of people with uncorrected eyesight problems, followed by India (477 million), Nigeria (95 million), and Indonesia (90 million), it says.

“[The sight problem is] linked to poverty elimination, access to quality work, a good education, gender equality, and a couple other [of the] Sustainable Development Goals [set out by the United Nations],” Chen says. “None of these can be achieved unless people have corrected eyesight.”

The impact can be felt in straightforward ways, such as the road traffic accident rate, he says. According to the World Health Organisation, more than 1.3 million people die each year from injuries they suffer in traffic accidents, and 90 per cent of them happen in low- and middle-income countries.

“If most people in the developing world do not have sight correction, then it is obvious to us that someone with poor vision is more likely to be involved in a road traffic accident,” Chen says.

He is launching research trials in six countries over the next three years to ascertain the causal links between poor vision and problems of social development, including road traffic deaths.

Most of those in need of prescription glasses in China suffer from myopia, or short-sightedness, which affects more than 45 per cent of primary school pupils and 86 per cent of university students, government figures from 2014 show.

“Asian kids tend to be driven to study all the time, so they don’t have enough outdoor time,” Chen says. “The proliferation of screen devices and the longer time kids spend on screens also contribute to poorer vision.”

Chen’s study shows 300 million of the 720 million people in China who lack corrective eyewear live in the countryside, which runs contrary to the popular perception that the myopia epidemic is confined to urban areas.

Although China has more than 28,000 ophthalmologists, 70 per cent of them are based in big cities and only 4,000 are qualified to conduct eye surgery, according to the China Medical Association. High distribution costs keep sales of glasses in rural areas down, even though China produces about 70 per cent of the world’s spectacle frames.

Chen says one of the most effective solutions would be to enable more health care workers and even schoolteachers to conduct basic eye examinations.

He founded a charity, Vision for a Nation, to tackle the same problem in Rwanda, East Africa, in collaboration with the government there in 2011. It grew into a national system to provide affordable eye care services to all citizens. More than two million of Rwanda’s 12 million people have had eye tests so far.

“The key to the success in Rwanda was developing a training protocol to train nurses in three days so they have enough knowledge to give a basic eye test,” Chen says.

An eye test can determine whether a patient has a serious eye disease that needs to be treated at hospital or is just in need of a pair of glasses.

The Chinese government started a five-year national action plan in 2016 to improve public services and awareness of eye health. But Chen is doubtful the plan will cover the 280 million migrant workers who are not entitled to health care benefits in the cities they live in because of the household registration system.

He hopes business leaders, policymakers, and the non-profit sector will work together to address the problem.

“While vision is a health issue, its connection to productivity, poverty, and education means that people need to think [about] it differently, allocate more resources and prioritise this issue,” Chen says, “because the pay-off is so huge.”