‘How can you be raped?’ Doctor’s words to transgender in India an example of the ‘transphobia’ that stops many getting health care

Health staff show ignorance, hatred or fear of patients who are transgender, despite it being officially recognised as India’s third gender. Many self-medicate rather than seeking health care, and suicide rates are high

Eleven years ago, Sohini Boral, a 29-year-old transgender woman, visited a government-run hospital in the eastern Indian city of Kolkata for consultation for a persistent fever. When she joined the women’s queue to buy a token, she was pushed away. The men, too, did not allow her to stand with them.

“I was 17, and had just started expressing my femininity by keeping my hair long and wearing women’s clothes and nail polish,” recalls Boral, who now works as a strategic information assistant at Amitie Trust, a network set up to improve the lives of sexual minorities, in Serampore, some 30km (18 miles) from Kolkata.

When she entered the doctor’s room, he unabashedly ran his eyes up and down her body and asked, “Why are you dressed like this?”

“I like to see myself in this get-up,” she told him.

“OK, sit for a while. Let’s talk about this. I want to know more about you. We could get to your fever later,” he said.

“And his very next question was, ‘What kind of genitals do you have?’” Boral says.

“That was enough. I left his room, shocked and traumatised by his behaviour,” she says. Boral never went to a hospital again in the next six years she was in Kolkata. She self-medicated for fever, stomach pain and allergies.

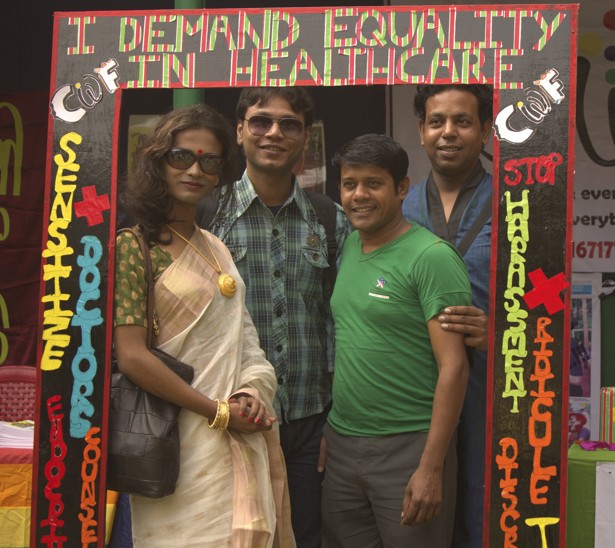

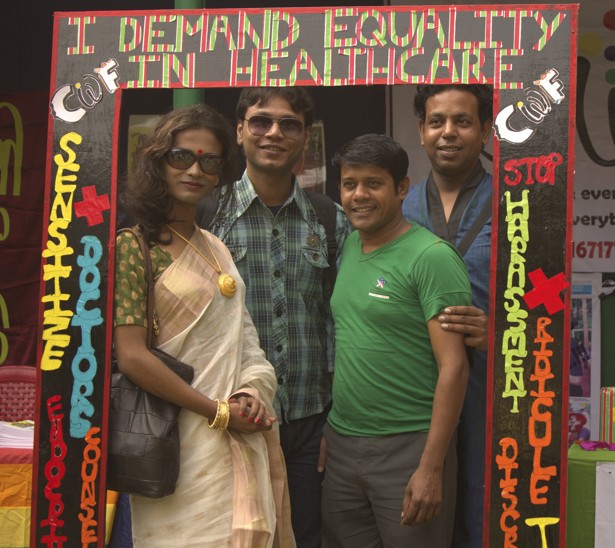

Transgender was recognised as the third gender by India’s Supreme Court four years ago. But like a lot of the reported 500,000 transgender people in India, Boral has experienced “transphobia” – extreme fear or hatred of transgender people – from various quarters, and especially health care workers. Insensitivity towards people who are non-binary (meaning they do not fully identify with being either male or female) and lack of understanding of gender dysphoria (the feeling of being emotionally and psychologically opposite to one’s biological sex) leads doctors and other hospital staff to ridicule them and sometimes even refuse treatment and care.

The Kolkata-based Civilian Welfare Foundation (CWF) works on transgender issues. In an unpublished study, the charity found that a transgender woman called Saikat died after a train accident because of a lack of timely care at a hospital that could not decide whether to admit her to a male or female ward.

This kind of confusion is quite common in Indian hospitals, as they do not have separate wards for transgender people.

Instead of treating me [for gang rape], the doctors were showing my body parts to trainees, saying this is how genitalia looks after castration

Abhina Aher is a Delhi-based transgender woman and the associate director of sexuality and gender rights at the India HIV/Aids Alliance. She says that people from her community admitted to hospital have often been asked to sleep near the toilets, as neither men nor women want them in their wards.

“They lie there unattended, without anyone to look after them, as most have been abandoned by their families. Peers from the community do not have the time to support them. The nurses are reluctant to touch them,” Aher says.

In 2012, when Amruta Soni, a transgender advocacy officer at the Vihaan Project in Patna, which runs care centres for HIV sufferers, arrived at a government hospital after being gang-raped, she wasn’t given emergency treatment.

“Instead of treating me, the doctors were showing my body parts to trainees, saying this is how genitalia looks after castration, and this is how a breast enhanced through hormonal treatment appears,” Soni says.

Later that year, when she contracted HIV, her counsellor at the antiretroviral therapy (ART) centre advised her against seeking treatment. ART helps infected individuals live a longer and healthier life.

“The counsellor told me not to waste my time, as I was likely to die within six months. Such is the stigma towards my community.”

Shuvojit Moulik, the founder of CWF, recalls the ignorance of a doctor when dealing with a transgender rape case. “When he attended to Tanushree, a transgender woman, after she had been gang raped, he asked: ‘How can you be raped’?”

Moulik says that, because it costs a lot of money to consult a doctor, transgender people in India use over-the-counter hormone pills indiscriminately, despite the severe harm these can cause.

For the entire 2009, I was being treated for what they called ‘madness’. I was kept in a mental asylum and given electric shocks

In the absence of good jobs, or medical insurance to cover expenses, many of those desperate for a sex change borrow money, beg or do sex work to pay hospital bills. Mumbai-based Dr Parag Telang, one of the handful of surgeons who conduct sex reassignment surgery (SRS) in India, sees many such patients.

He performs at least two sex reassignment operations and around 10 breast augmentations for transgender people every month.

One of the reasons transgender people in India face discrimination and ridicule is the lack of regular jobs in which they can be their transgender selves. Aher says this has made transgender people reluctant to look after their own health.

“The stress of day-to-day subsistence, self-guilt, self-hatred and sorrows associated with lovers and family members have become reasons behind increased alcohol consumption and use of recreational drugs,” Aher says.

In a study of 300 Indian transgender women, 37 per cent were found to consume alcohol at least once a week. “Mental-health issues are huge among the transgender community,” Aher says. According to a 2016 study, the suicide rate among transgender people is about 31 per cent, and 50 per cent have attempted suicide at least once before their 20th birthday.

There is also the burden of reparative, or conversion, therapy. Boral’s colleague, transgender woman Maya Das, 29, was taken to psychiatrists to “turn her into a straight man”.

“For the entire 2009, I was being treated for what they called ‘madness’,” she says. “I was kept in a mental asylum and given electric shocks.” During the period, Das says she bloated to double her size, her hair fell out until she went bald, and depression kept her awake at night.

Her liver was badly affected by the strong medicines and after nine years she is still recovering from the side effects of the “therapy”.

The government has sought ways to make health care accessible for the transgender community.

The Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill, which was introduced to parliament in 2016 to formalise the Supreme Court judgment of 2014 that recognised transgender as a third gender, proposed punishing with six months to two years’ imprisonment anyone who harmed the physical or mental health of a transgender person.

The bill also covers matters such as the provision of government services for hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and sex reassignment surgery, medical insurance, and a review of the medical curriculum for doctors and medical research. After almost two years, however, the bill is yet to be finalised in parliament.

As people see more of us, they will know that we’re like them. We eat, sleep and fall sick in just the same way

The bill is one thing, says Aher, but “sensitisation of doctors and medical staff [to] the socio-economic issues of the community is equally important to deal with transphobia”.

Boral and Moulik emphasise the importance of transgender people being visible in society. “The government hospital I now visit in Serampore has a robust influx of transgender people by virtue of HIV intervention programmes run by nearby NGOs,” Boral says. That means there is no more gawking from onlookers as she experienced in Kolkata.

“As people see more of us, they will know that we’re like them. We eat, sleep and fall sick in just the same way,” she says.

Last year, the southern Indian state of Kerala announced that all its government hospitals would provide free outpatient clinics exclusively for transgender people.

The first one was set up at the Government Medical College in Kottayam in June last year. It provides free services, an environment free of bias, and a safe space to seek advice from physicians, plastic surgeons, endocrinologists, dermatologists and psychiatrists without being sniggered at or asked personal and unethical questions.

More than a year after it opened, Dr Sue Ann Zachariah, the coordinating medical officer and doctor in charge at the clinic, says she has seen a large change in the attitudes of staff and patients at the hospital. “No one stares or points fingers at transgender persons now,” she says.

Sixty people have registered at the pilot clinic so far. Is that anywhere near enough given there are nearly two million people living in the district?

“It isn’t,” Zachariah says. “But there is no point in having more clinics unless we can fulfil the requirement of HRT and SRS, which is what they come for. Once our doctors are trained for that next year, the government will probably look at setting up more.”

Dancing queens

Fourteen years ago, Abhina Aher founded India’s first transgender-led dance troupe in Mumbai with the hope of changing stereotypes about the transgender community. She thought that having a collective of professional dancers covering classical, contemporary and folk dance would dispel the misconception that transgender women in India only perform vulgar dances wearing gaudy make-up.

The troupe’s members cherish the inclusive approach and the strong familial support the troupe offers.

“When we started, almost 30 per cent of our members were living with the HIV infection,” Aher says. But a lot of them were unwilling to pursue treatment for fear of reprisal upon disclosure of their condition.

Once the senior members of the collective began talking to their fellow dancers about healthy living and the treatment options available, the ones with HIV felt more in control of their situation. Seeing others living and managing their condition gave them hope that HIV did not always mean death.

“We constantly talk about good health and medical treatment being a human right, and convince them that they are an important part of society and need to take care of their health,” Aher says.

Dance has helped the group’s members deal with their insecurities, reducing alcoholism and mental health problems.

“They know that even if the entire world abandons them on learning of their HIV status, their Dancing Queens family won’t.”

The jobs they have landed via connections made through Dancing Queens have helped support their treatment. And free-flowing conversations on dealing with stigma and discrimination have made their colleagues more aware of the problems they face.

“At Dancing Queens we like to believe that much of the transphobia stems from ignorance, not hatred,” Aher says.