Why you need to listen to your grumbling appendix, even after years of putting up with it

- If you have endured bouts of abdominal pain over the years, you may suffer from what some doctors call chronic appendicitis

- Because of a lack of classic symptoms, medical opinion is divided on whether it exists, and how it should be treated

The pain first hit when I was a teenager: an unrelenting grinding in my lower abdomen, as if my internal gears were gummed up. A fleeting thought crossed my mind – could it be my appendix? – but I dismissed it, since I felt fine the next day.

Throughout my young adulthood, the grinding pain recurred every few weeks or so. When it hit, I’d clench my jaw and curl up in the fetal position, but within a few hours, the attack would pass. I wasn’t concerned enough to have a doctor check me out since things receded quickly.

But then in my early 30s, I had what seemed like just another bout of this pain, but this time, it didn’t go away. I headed to the hospital, where I learned that my appendix was about to rupture.

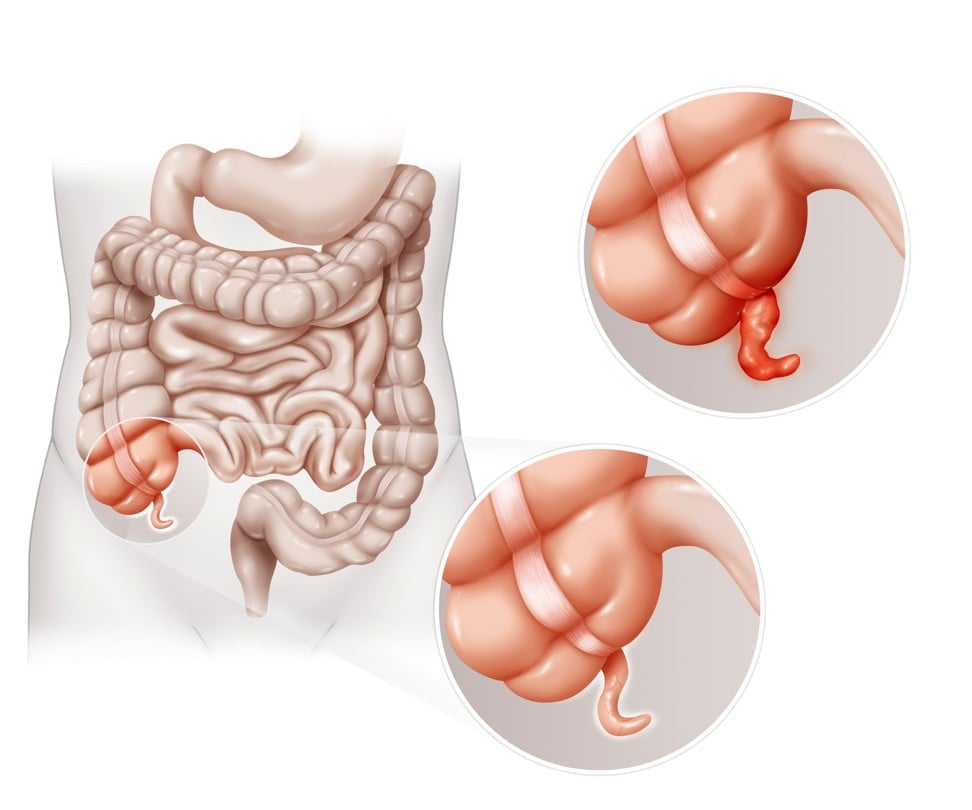

The appendectomy performed on me revealed the likely origins of the mysterious pain that had plagued me for more than half my life. Appendicitis, it turns out, isn’t always acute. Some people can limp along for years with appendix-related pain from some sort of inflammation or obstruction – a condition known as chronic appendicitis.

Debate has long raged among physicians about whether the condition dubbed “grumbling appendix” is real.

“Chronic appendicitis can be controversial and is often misdiagnosed,” writes radiologist David Kim of the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Specialists used to consider chronic appendicitis “like the Monster of Loch Ness – something that was out there, but no one had seen it properly,” says Ran Goldman, a paediatric emergency doctor at the University of British Columbia and the BC Children’s Hospital, who has co-written a study on chronic appendicitis in children.

But while controversy about the diagnosis still simmers, the consensus has moved somewhat toward acceptance of chronic appendicitis as a medical phenomenon.

In the community of gastrointestinal experts, “People are recognising more and more that there is an entity like this,” Goldman says.

A case report last year in Annals of Medicine and Surgery describes a patient whose 18 years of symptoms resolved as soon as his appendix was taken out. And a 2015 paper argues that clinical cases from the past two decades support the theory that chronic appendicitis, while rare, does exist.

Part of the mystery stems from how difficult it is to diagnose.

The signs of acute appendicitis are fairly clear-cut: pain in the lower right part of the abdomen, loss of appetite and low-grade fever.

But with chronic appendicitis, not all of these symptoms may be present, and even when they are, they may clear up for a while. A white blood cell count, often elevated in acute appendicitis, may come back normal.

What’s more, symptoms of chronic appendicitis can overlap with signs of more common gastrointestinal conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), Crohn’s disease or even cancer.

(I assumed for years that I had IBS, which causes abdominal pain and diarrhoea, though the label didn’t quite fit; I never needed Imodium.)

To arrive at a possible diagnosis of chronic appendicitis, clinicians first need to take a detailed history, says Jennifer Goldstein, an internist at Pennsylvania State University’s Milton S. Hershey Medical Centre. Recurrent, intermittent pain in the area of the appendix might tip her off – “a patient who’s saying, ‘Why does this keep happening? I don’t have an answer.’ ” The pain might last for a few hours or days and then go away.

But a medical history by itself is not enough, Goldstein says. In recent years, specialists have relied on high-resolution imaging technologies such as ultrasound and computed tomography (CAT) scans to detect the often subtle signs of chronic appendicitis when a history and physical exam yield no clear answers.

“Imaging probably should be done on patients that have recurrent abdominal pain,” Goldman says. Ultrasound, he added, is a good first step because it is less invasive than a CAT scan, which uses radiation.

Since chronic appendicitis is so rare, most imaging studies of people with abdominal pain will show a normal appendix – not the inflammation or blockage often seen in acute appendicitis. Certain findings do suggest ongoing issues with the appendix – a thickening of the organ’s wall, for instance, or a cyst on the appendix that is filled with mucus.

If I’d had an ultrasound or CAT scan done when I was a teen, notes University of Manchester gastroenterologist Peter Whorwell, it’s possible doctors might have seen one of those things and would have picked up on my appendix issue much earlier.

When doctors suspect chronic appendicitis, they face a difficult decision: Should they wait and see whether the pain clears up on its own – or should they go forward with an appendectomy, even though the situation is not yet life-threatening? Specialists say their judgment depends on the specifics of a given case. Sometimes, doctors may prescribe antibiotics to avoid having to perform surgery, which always carries risk. But follow-up exams are crucial in any case.

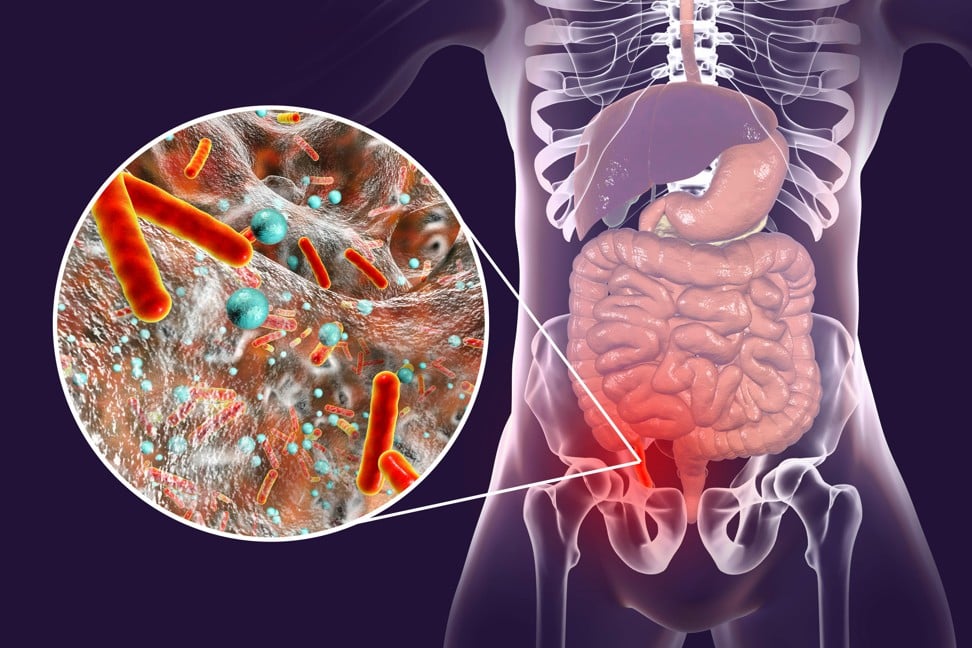

“Some cases resolve,” Goldman says. “Others become so acute that there is no question the patient needs to go to the operating room.” An inflamed appendix that bursts can be life-threatening because it ejects bacteria into the abdomen, spreading infection.

Clear signs of infection or swelling on a CAT scan, along with significant ongoing pain, may convince doctors to go ahead with surgery.

“An appendectomy is a tried and true operation,” says gastroenterologist Seth Crockett of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a spokesman for the American Gastroenterological Association. “Most surgeons are comfortable doing it, and it’s been around forever.”

Still, few doctors choose this option lightly.

“The default approach is, if an appendix is inflamed, you take it out,” Whorwell says. But some of his patients have had serious post-operative pain after having abdominal organs removed – especially patients with IBS, who often have high pain sensitivity. So Whorwell opts for a conservative approach, advising patients not to have an appendectomy unless there’s a compelling reason for it. He may re-evaluate later on if their pain persists or gets worse. If Whorwell had seen me as a teenager and my scans showed nothing definite, he says, “I’d have told you to hold on to your appendix.”

At the time, I probably would have agreed with him. The pain bothered me only for a few days a month at most. Besides, I didn’t even know for sure whether my appendix was the cause.

But in the end, I’m glad my symptoms progressed enough to land me in the accident and emergency department. After I had my appendectomy, I was gobsmacked and overjoyed to find my recurrent pain was gone for good, nearly 20 years after it began.

The Washington Post