Blind women trained to find breast cancer lumps by feel are better than doctors at the task

- They are called medical tactile examiners, or MTEs, and they work in India, Mexico, Colombia, and Austria, using their sense of touch to find breast nodules

- The women spend much longer than doctors on examinations, and can find smaller lumps; in India their detection rate is 100 per cent so far

Dressed in a pink uniform, Hasiba Rani starts her first consultation of the day at CK Birla Hospital for Women in Gurgaon outside the Indian capital, New Delhi. After noting the patient’s medical history, she spends 30 minutes on a physical examination. Rani is “looking” for lumps or nodules in the patient’s breasts, only she cannot see. She is blind, and relies on her sense of touch.

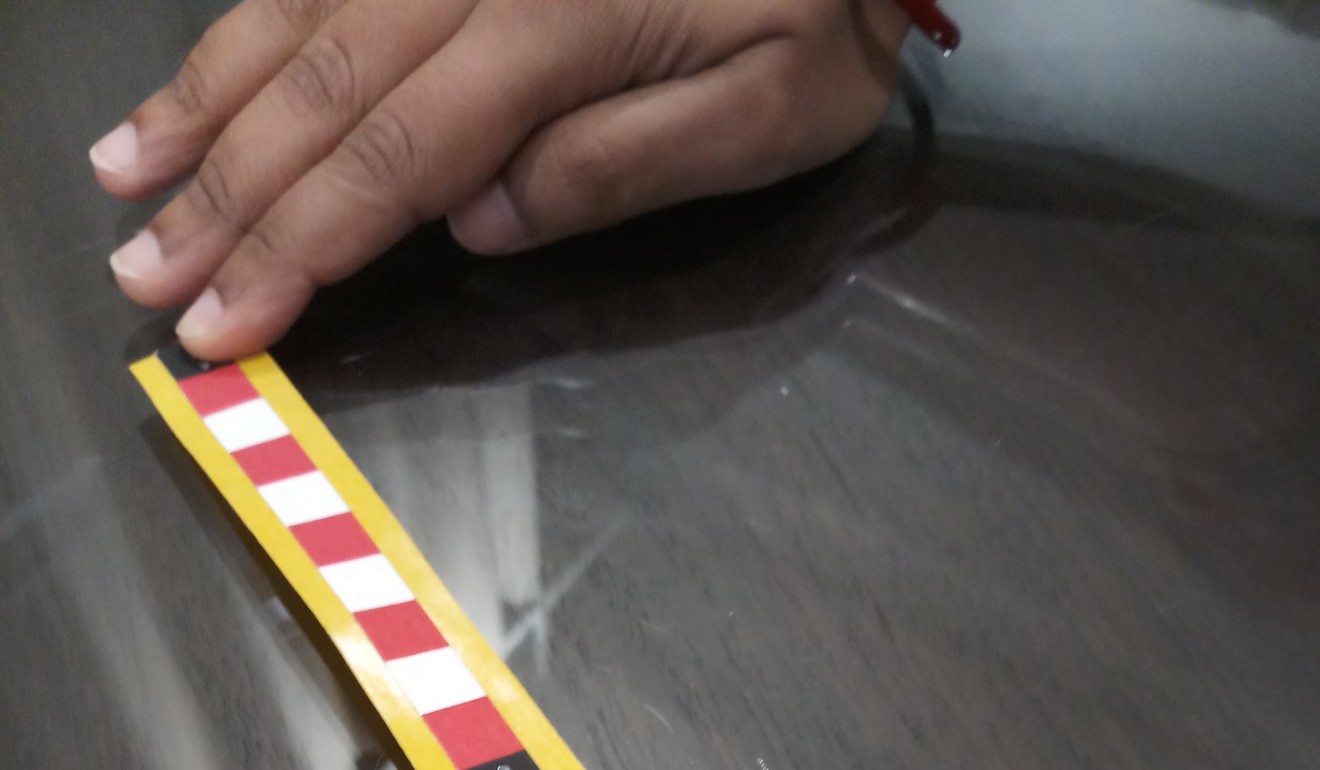

Starting with the lymph nodes in the neck, she moves down to the collar bone, underarms, and every single centimetre of the breasts. She is guided by adhesive strips marked in Braille to ensure she leaves no part untouched and to help her report to the doctor, if she finds a lump, its exact location.

Rani, 25, has a serene demeanour, a soft voice, and a quiet confidence. She is one of seven blind Indian women who have been trained as medical tactile examiners, or MTEs, a role created for women who are blind and have extra sensitivity in their fingertips, either from having learned Braille or simply from having developed a greater sense of touch to cope with their loss of vision.

This sensitivity is being harnessed for the early detection of abnormalities which could be indicative of breast cancer. Globally, more than two million women are diagnosed with breast cancer each year, according to the World Health Organisation. According to a 2018 report by the Indian Council for Medical Research, 50 per cent of breast cancer patients visit a doctor only when their cancer is at stage three, and 15-20 per cent when it is at stage four, the highest stage, owing to the low level of screening.

If women are physically examined by a doctor, palpation usually lasts a couple of minutes at most. Doctors are too busy. In a flash of insight in 2006, gynaecologist Dr Frank Hoffman, based in Duisburg, Germany, wondered if a blind woman could do a more thorough job than doctors of detecting small lumps – crucial to catching breast cancer early.

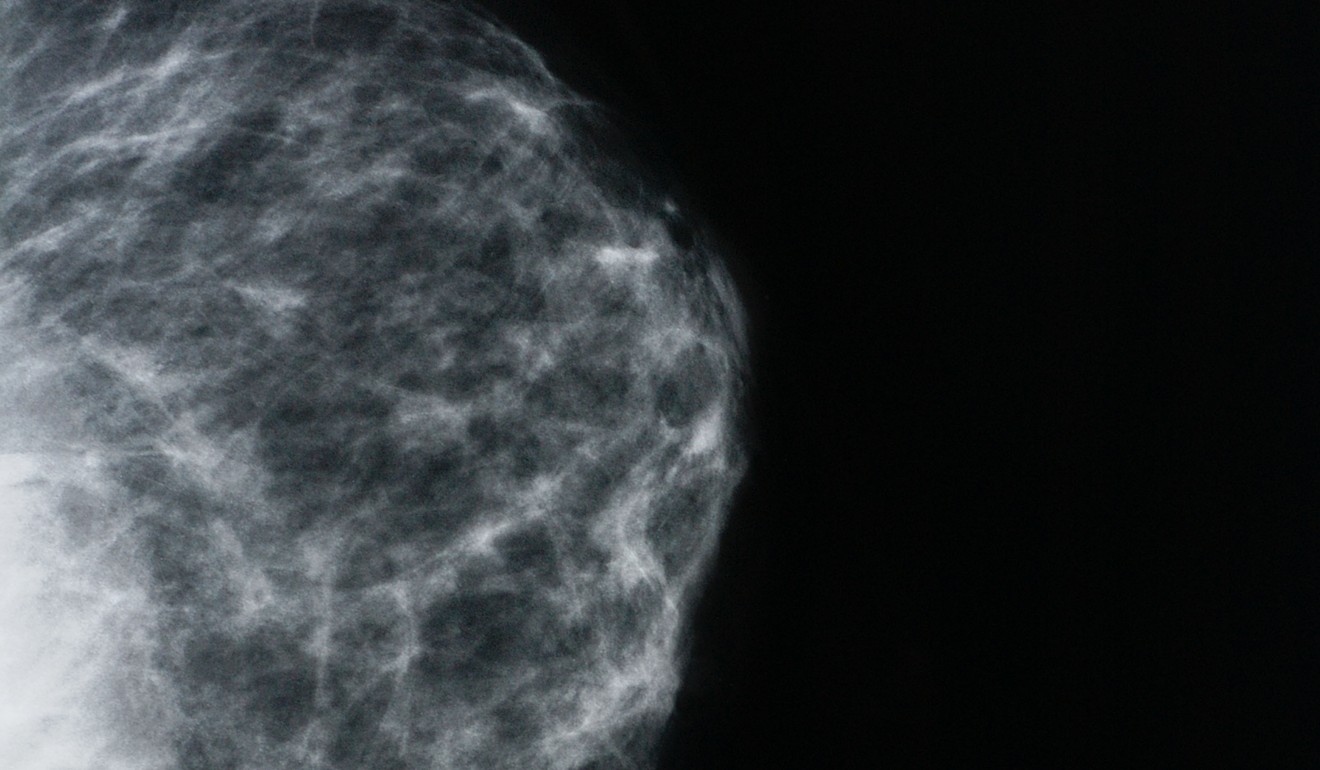

Doctors usually find tumours of between 1cm and 2cm in diameter. Hoffman found that blind examiners could detect lumps of between 6mm and 8mm in diameter. The idea was worth exploring because cases of breast cancer in younger women are growing, but mammogram screening is provided only to women aged 50 or over in most countries; in India it is 45 and above. Younger women, though at risk, were effectively being left unscreened.

In India, says Dr Mandeep Malhotra, breast cancer and oncoplasty expert at CK Birla Hospital, the peak age for breast cancer is falling. “It varies across India but, for example, in the northeast it peaks at 35, in Delhi it is 45 – so we need to start screening women around 10 or more years before the current global guidelines of 45-50,” he says.

Hoffmann founded an organisation, Discovering Hands, and devised a course in 2010 to train blind women to become MTEs. Around 17 work in Germany. Others work in Austria, Colombia, and Mexico.

Drug maker Bayer India has worked with the National Association for the Blind (NAB) in New Delhi to identify suitable women and pay for them to undergo an intensive, nine-month MTE training course. Blind women trained in Germany conduct the classes.

The first batch of seven MTEs in India are working at Fortis Hospital, a national chain, Medanta Hospital, also in Gurgaon, and at Birla Hospital. Between them they have performed more than 500 examinations since October 2018. Of these, 57 were reported to doctors as suspicious and all 57 were later confirmed as positive. A further six MTEs will complete training this month and will be placed for internships in hospitals.

For Rani, the training has turned her disability into a gift and a means to independence. She began losing her eyesight from retinitis as a teenager. By the time she graduated from college, she had no sight left at all. The next four years were spent deep in depression: her dream of becoming a doctor was extinguished.

With her parents’ support, she took up teaching computer skills to blind children at the NAB. When she heard of the Bayer training, she applied and passed the touch screening test to qualify. Candidates need to be able to learn medical terms, have soft skills, know computers, possess some English and have both an acutely developed sense of touch and good memory retention because, not being able to take notes during training, they must be able to memorise a lot of information, which is helped by recordings of lectures.

Rani’s job allows her to live as a lodger with a family. “A blind person always feels dependent on others as though they have nothing to offer. Although my dream of being a doctor was destroyed by my blindness, with this job, I am also, in a way, helping to save lives,” she said.

The patient Rani examined that morning, 46-year-old housewife Seema Sondhi, had been tense as she had not had a check-up in some time. Rani’s examination revealed no abnormalities. “It was the most detailed examination I have ever had. It put my mind at rest. I don’t need a biopsy and for that I’m grateful to Rani,” said Sondhi.

For the purpose of this article, Rani gave me an examination. It was far and away more thorough than the fleeting palpation you get from most gynaecologists. So advanced is her sensory awareness that, at one point, when I unconsciously moved the position of my arm a fraction, Rani, even though her hand was not even touching my body at that point, sensed my movement and made me return my arm to its original position.

For Neha Suri too, becoming an MTE has given her a purpose and financial independence. She went blind from retinitis before her husband died of bone cancer in 2016 at the age of 43, leaving her to raise her son alone. She works part-time, commuting by train for three hours between her home in Rudrapur and Fortis Hospital.

“My family is very loving, but I wanted to be independent after my husband’s death. After seeing the way he suffered, this training was ideal for me because I wanted to help women avoid cancer. I was very nervous at first. I was frightened of missing a lump. But I am confident now. I see about 20 patients a month,” she said.

For Bayer, training MTEs is a way to help blind women live a life of dignity and boost the early breast cancer detection rate. “A physical examination is particularly important here because Indian women have dense breast tissue. About 30 per cent of women are not amenable to mammograms due to this high density. The MTEs are given special training for dense tissue,” says Suhas Joshi, the head of corporate social responsibility for Bayer South Asia.

Although my dream of being a doctor was destroyed by my blindness, with this job, I am also, in a way, helping to save lives

Malhotra echoes this view, saying that mammograms are more effective on American and European women than on Indian women. Since the breast tissue is dense, it means offering mammograms to younger women may not necessarily help to detect cancerous cells.

“In fact, studies at the Tata Memorial Cancer Hospital in Mumbai have shown that mammogram screening has not led to better survival rates,” he said.

His other point is that India does not have the resources to install millions of mammogram machines, ultrasound machines, and MRI equipment. But it has millions of blind women, some of whom can be trained to detect abnormalities.

If an MTE finds something suspicious, a doctor verifies it and interprets it, to decide how to proceed, usually with an ultrasound or mammogram. German research findings on MTEs’ diagnostic accuracy were published in January in the medical journal Breast Care. It said the accuracy of MTE examinations on patients who had not had prior surgery was similar to that achieved through a clinical examination.

In the next three years Bayer plans to have trained 21 MTEs, who will have examined 45,000 women. Later the programme will be extended to other cities in India. Meanwhile, to spread awareness of the MTE screening, the company plans to offer examinations at special camps.

For Malhotra, who is passionate about the role that MTEs can play, it is not a question of either/or. Doctors and patients need mammograms and all the other technology that is used to detect breast cancer.

“Technology is vital but has limitations. The human touch is vital but has limitations. MTEs cannot replace technology. They can complement technology. That’s the key,” he says.