Korean New Wave cinema: how Shiri, Christmas in August and other movie hits put South Korea on the world map

- Before the Korean New Wave exploded into life, South Korea’s moviegoers were happy to watch Hollywood films in cinemas and follow American stars

- The box office success of Shiri in 1999 changed all that, and spawned blockbusters like Silmido, Friend and Taegukgi

The Korean New Wave started a boom in domestic cinema during the late 1990s and early 2000s. It was partly instigated by the phenomenal success of the action thriller Shiri at the local box office in 1999.

Before the New Wave, South Korea did not have a home-grown commercial cinema of note, and viewers preferred to watch Hollywood films in cinemas and follow American stars.

The box office success of Shiri, which was released in 1999, opened the way for a blossoming of commercial films, and introduced the term “Korean blockbuster”, which came to describe big-budget – for Korea – crowd-pleasing movies like Silmido, Friend and Taegukgi, films which quickly smashed box office records in the country.

Audiences who had generally been indifferent to Korean films turned out in force to see such movies, and they were supported by critical acclaim. Korean films became lucrative as a result, and investment poured in. This boosted the careers of a group of directors including Park Chan-wook, E J-yong and Kim Ki-duk, some of whom had already seen success in the late 1990s, and led to the production of a wide range of films that spanned genres.

The film boom meant that talent was needed in front of the cameras, and this led to the establishment of a star system, with stars like Choi Min-sik not only matching, but replacing, US stars as fan favourites. In terms of adulation, the movie stars of the period were a precursor of today’s K-pop stars.

The effects of the New Wave were felt in the art-house sector as well as the commercial sector. A peculiar characteristic of Korean New Wave films was that some were commercial enough to play in cinemas at home but interesting enough to intrigue the foreign art-house audiences at film festivals.

Korean art house films had provoked quiet interest at festivals since the early 1990s, with the works of filmmakers like Park Kwang-su (To the Starry Island) and the country’s towering directorial genius, Im Kwon-taek (Sopyonje and around a hundred others), but they were generally regarded as marginal entries.

Commercially oriented films like E J-Yong’s An Affair had also pleased audiences at specialised Asian film festivals like Italy’s Udine Far East Film Festival.

But in the 2000s, Korean films became the “in thing” at international festivals, and achieved high-profile showings at major festivals like Cannes and Venice.

The success of the Korean New Wave primed international audiences for hallyu, the pop-cultural phenomenon that saw Korean television shows and musical acts become popular at first in Asia, and then all over the world.

What was so special about Shiri?

A quick answer to that would be the box office. Shiri, directed by Jacky Kang Je-gyu, was produced on a budget of around US$5 million but took US$26 million at the box office. Six million people in South Korea went to see it, with 2.4 million of those coming from Seoul. It topped the year-end charts as Korea’s highest-ever grossing film at the time.

In terms of plot, story and direction, Shiri – a mixture of espionage, romance and action – was little more than a competently staged action film. But it touched a chord with Korean viewers.

Korean audiences loved the fact Shiri looked as slick as an American film, and its accomplishments, both in technical and box success terms, evoked a sense of national pride. Koreans suddenly felt that their films could compete with those from the US, and proud audiences flocked to show their support.

Shiri ’s story revolves around an undercover North Korean agent who falls in love with the South Korean agent who is trying to capture her.

The movie was groundbreaking in the way that it depicted a North Korean communist as a sensitive human being – a romantic lead, no less, albeit a murderous one. North Koreans had previously been depicted as evil communist stereotypes in South Korean popular culture.

Released during the time of the South’s Sunshine Policy, Shiri played into an optimism that a rapport could be achieved between the South and the North, an idea that was taken further and clarified in Park Chan-wook’s Joint Security Area.

What other New Wave films are important?

Korea had produced a number of lower-budget commercial films like the romantic The Contact before Shiri. These films, which were generally well received at home, paved the way for the post-Shiri surge. A small coterie of international critics, notably Variety’s Asian film expert Derek Elley, had already begun to comment on the slick and professional qualities such films displayed, and had written about them in the Western press.

Critics at home and abroad were quick to identify a new style of Korean film, noting strong commercial appeal and the directors’ propensity to mix genres – for instance, combining horror with a high school drama, or gangsters with comedy. The films also made use of tight narrative structures reminiscent of American movies, even though they were uniquely Korean in content and attitude.

Below are some of the New Wave films that created waves.

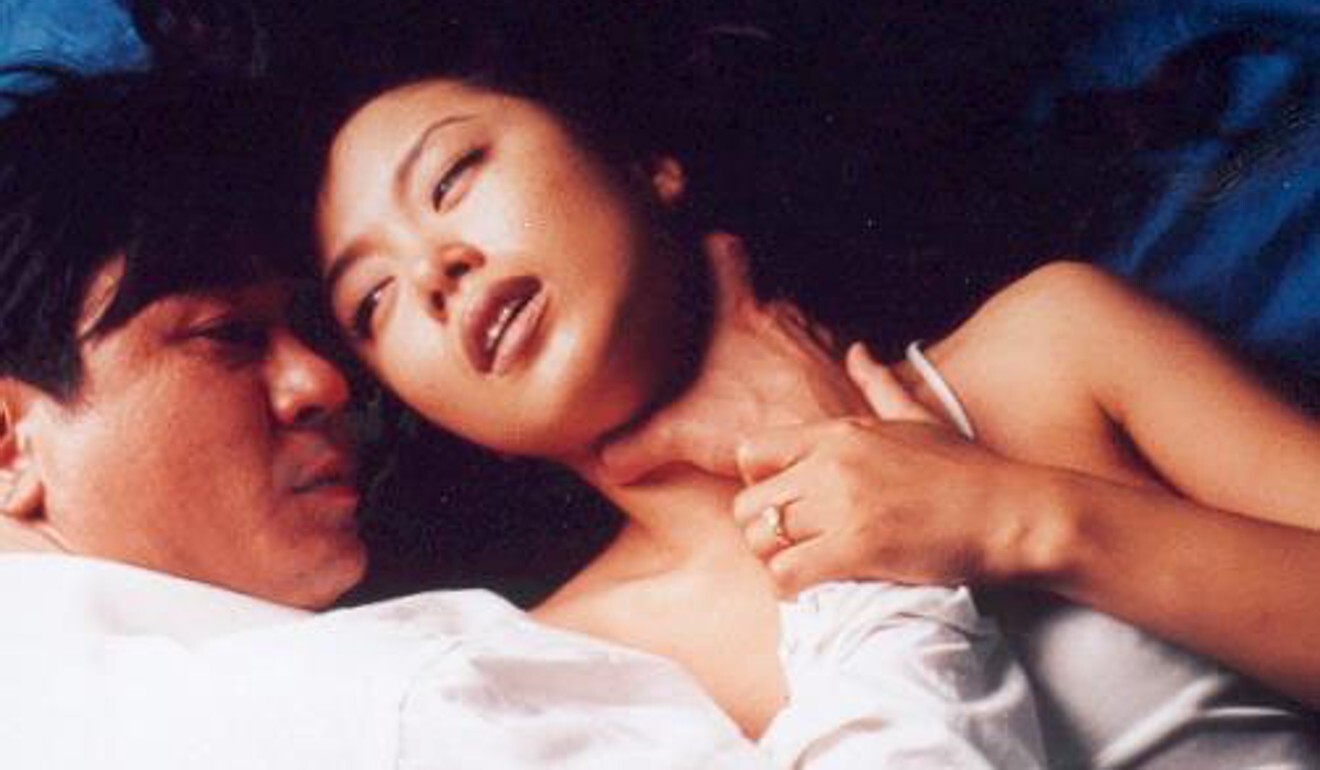

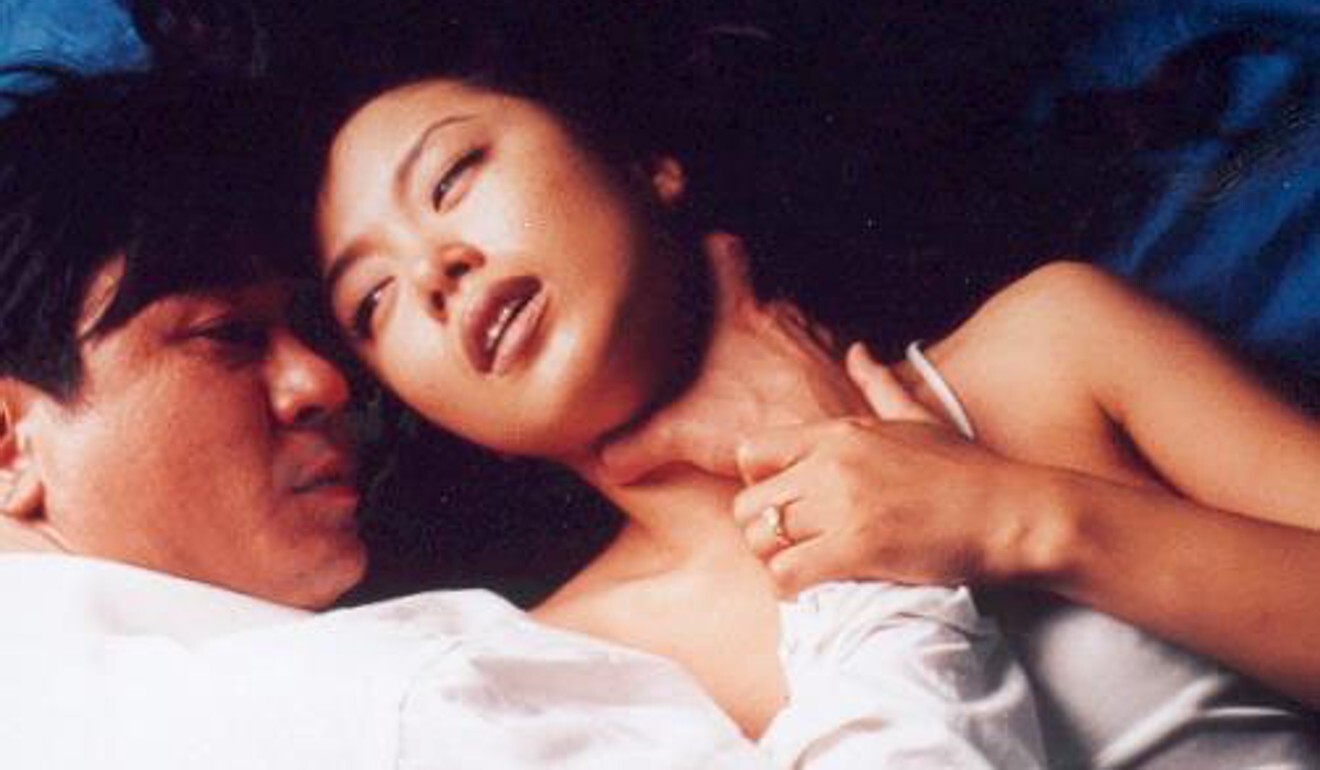

An Affair (1998)

Falling somewhere between a doomed romance in the manner of Douglas Sirk and a weepy television drama, An Affair marked the debut of director E J-Yong and the breakthrough of leading man Lee Jung-jae.

Veteran actress Lee Mi-sook plays a woman who falls in love with her younger sister’s dishy fiancé. The way the woman courageously takes control of her own destiny struck a chord with female viewers at home.

Christmas in August (1998)

Director Hur Jin-ho stood slightly outside the nascent New Wave scene, and this touching – and, of course, tragic – romance was considered a bit different at the time. Full of sensitivity, and compared to Francois Truffaut films by critics, it has been an enduringly popular film and has gained a cult-like following. The movie set actor Han Suk-kyu on the road to becoming a big star.

Peppermint Candy (1999)

Perhaps the best work by novelist-turned director Lee Chang-dong, this unrelenting drama shows how peer pressure and indoctrination can pervert even the most sensitive soul. The acting by Sol Kyung-gu and Lee’s direction are superb. One of the best Korean films of the 1990s.

Happy End (1999)

Brutal violence played a part in many Korean New Wave films, and it provided the twist in this movie by Jung Ji-woo, which begins as a typical romance before heading into psychodrama territory.

Lies (1999)

Art-house director Jang Sung-woo’s story about a sadomasochistic relationship between an older man and a young girl fails on all levels, but its racy subject matter still made it a talking point among critics and audiences when it premiered at the Busan International Film Festival.

The director was praised for challenging conservative sexual norms, showing the risk-taking approach of some of the New Wavers.

Il Mare (2000)

A cute romance seemingly influenced by the work of Japanese director Shunji Iwai, Il Mare tells of two lovers who communicate across time via letters posted in an old postbox. Tragedy ensues, of course.

The movie brought actress and former model Jun Ji-hyun to the attention of movie audiences, and shows the tone of the lighter efforts of the New Wave. It was popular enough to spawn a Hollywood remake.

Joint Security Area (2000)

Park Chan-wook’s film deals with the friendship that arises between two South Korean border guards and their counterparts in North Korea.

A well-judged drama that develops into a fully-fledged tragedy, the movie dared to say that, beneath the politics, communist citizens from the North weren’t any different to those from the South. Another box-office smash in Korea.

Friend (2001)

This big-budget gangster/coming-of-age drama owed a debt to Hong Kong gangster films, yakuza films, and Martin Scorsese’s work, and its potent mixture of harsh violence and sentimentality are common characteristics of the Korean New Wave.

By the time Friend was released, audiences were judging Korean films as “well made”, something that reflected the public’s feelings about Korean-made products in general.

My Sassy Girl (2001)

Jun Ji-hyun, in her breakout film, plays a gutsy young girl who puts an admirer in the shape of Chae Tae-hyun through his paces in a romantic comedy which pushes all the right buttons. The character’s independent spirit played well with female audiences.

Sympathy for Mr Vengeance (2002)

Uncompromising to the point of nastiness, this unpleasant sortie through some warped minds wasn’t much liked in Korea due to the excessive violence.

Director Park Chan-wook refined the revenge theme for his masterpiece Oldboy here. New Wave actress Bae Doona gives a typically idiosyncratic performance.

Taegukgi (2004)

Jacky Kang Je-gyu’s blockbusting follow up to Shiri showed how the New Wave directors used the Korean war as a backdrop for spectacular entertainment rather than political propaganda, appealing to a younger generation of viewers who had not lived through it.

Viewers also admired the high-class production values.

How did the films become so successful internationally?

Cinematic new waves must be genuine outpourings of talent to succeed and sustain themselves, and that was certainly true of the Korean New Wave. But matters were helped internationally by a skilful publicity organisation in the form of the Korean Film Council (KOFIC) and a powerful way of disseminating information, in the form of the newly established Busan (then called Pusan) International Film Festival.

KOFIC acted as a one-stop shop for those interested in Korean films at festivals, and instead of just focusing on foreign distributors, it actively courted international film critics.

Busan quickly became the venue to promote Korean films, and foreign critics were treated like royalty in its first years – they were provided with their own personal full-time guides to the city and given unlimited access to the filmmakers.

The openness and efficiency of the two organisations played a major part in disseminating news of the new cinematic wave abroad. The rest, as they say, is history.

Want more articles like this? Follow SCMP Film on Facebook