Frank Sinatra: the voice for every generation

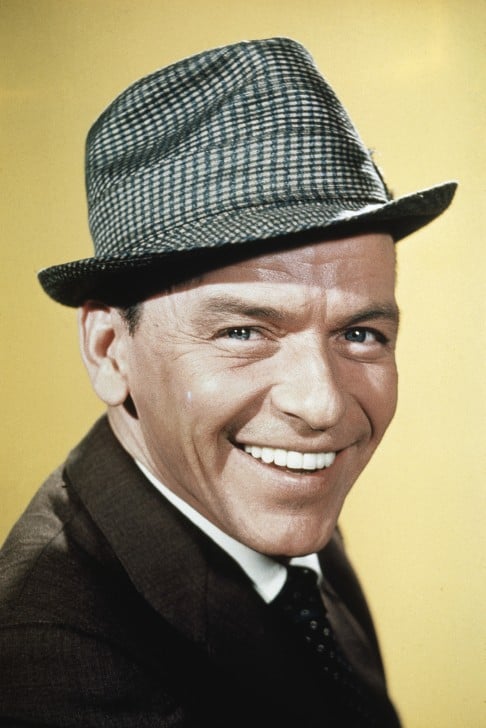

December 12 marks the centenary of Ol’ Blue Eyes, a man who transformed American song. Dan Deluca reflects on how Sinatra continues to speak to each generation anew

The other night, I got a text from a friend who was engaged in a barroom discussion. It was a greatest-concerts-ever debate, and the question was this: what are the three best shows you’ve ever seen?

I knew I’d have to mull that one for a while. I have an answer at the ready for No 1: Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band at the Spectrum in South Philadelphia in December 9, 1980. It was the night after John Lennon was murdered, and also the night after I had seen Springsteen for the first time.

But I’m not going to write about the best shows I’ve seen, and not about Springsteen, either. Instead, the question got me thinking about the shows I wish I could live through all over again, which is something different. That brings me to a different guy from New Jersey, who would have been 100 years old on December 12 if he had turned out to be as truly indomitable in the flesh as his music often made him sound. A guy who, as Springsteen once put it, had “a voice filled with bad attitude, life, beauty, excitement, a nasty sense of freedom, sex, and a sad knowledge of the ways of the world”.

Yes, ladies and gentlemen, The Voice himself: Frank Sinatra.

I don’t think I would put any of the times I saw Sinatra perform live in the best-shows-I-ever-saw category. They were all towards the back end of a storied career. Other competitors for those honours might be The Clash at Bond’s International Casino in New York in 1980, or Nirvana in Philadelphia in 1991.

Besides, I’m really not crazy about the idea of looking back and revelling in great shows of the past. The whole point of going to see live music is built on the stubborn hope that something magical might be on the cards, or, as Sinatra sang on the 1964 album It Might as Well be Swing, in a song written by Cy Coleman and Carolyn Leigh, while accompanied by Count Basie and His Orchestra, under the direction of Quincy Jones: The Best is Yet to Come.

A voice filled with bad attitude, life, beauty, excitement, a nasty sense of freedom, sex, and a sad knowledge of the ways of the world

So when the question came up, I didn’t think of any of those shows I mentioned above. Instead, I immediately flashed on the times my father took my mother and brother and me (and, usually, a larger posse) to see Sinatra in Atlantic City after casino gambling came to town in 1978 – “always sitting right up front”, as my mother recalled the other day – and the Chairman returned to his old stomping grounds to play Resorts International just up the boardwalk from where I grew up in Ventnor.

Those nights – at Resorts, and later the Golden Nugget and the Sands – flashed partly because I’ve been on a Sinatra jag lately, sampling various Ol’ Blue Eyes products flooding the marketplace to capitalise on the centennial of the man who was fond of raising Jack Daniel's with the toast: “May you live to be 100, and may the last voice you hear be mine.”

This year, a box called The Ultimate Sinatra came out that kicks off with the tender 1939 recording All or Nothing at All. That song is also the title of Alex Gibney’s excellent two-part documentary that ran this year on HBO. It’s a tidy summation, and revisiting Sinatra’s recordings with Capitol from the 1950s, particularly those with arranger Nelson Riddle, always makes for a sublime experience.

I’ve also been dipping into The Chairman, the 900-page second volume of James Kaplan’s biography. Not sure I’m going to like it as much as my favourite Sinatra books – Pete Hamill’s slim Why Sinatra Matters (1999) and Will Friedwald’s authoritative Sinatra! The Song is You: A Singer’s Art (1997) – but it seems to be the exhaustively researched, fair-minded bio that Kitty Kelley’s unauthorised His Way certainly was not.

One more box to look forward to, due out November 20, A Voice on Air (1935-1955) collects radio broadcasts from the early stages of his career, reaching back to his beginnings with Harry James and Tommy Dorsey and chronicling the rapid ascent in which the skinny kid from Hoboken sent bobby-soxers into ecstasy in a teenage ritual that would be repeated by fans of everyone from The Beatles to One Direction.

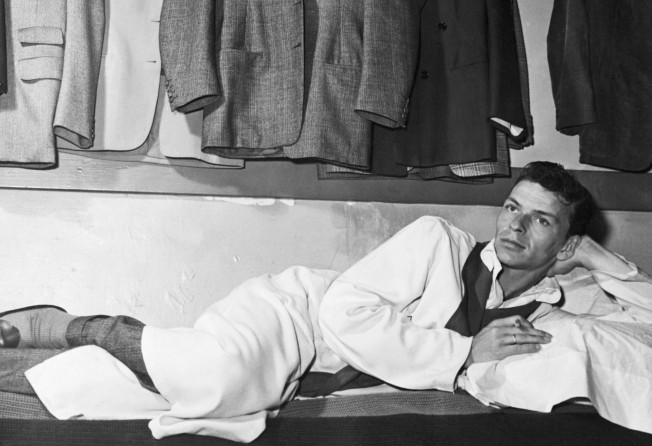

All this stuff keeps Francis Albert Sinatra alive 17 years after his death in 1998. He had been born in 1915 as the only child of a midwife mother and a boxer turn tavern-owner father, who went by the name of Marty O’Brien so he could earn a living in Hoboken’s Irish-only neighbourhood.

The Sinatra family lived on the Italian side of town (neighbourhoods were segregated by ethnicity and race at the turn of the century). According to the Hoboken Museum, Sinatra’s humble beginnings “shaped his early career and imparted a cocky but relatable image, which helped make him an icon”.

“Frank Sinatra was the pinnacle of style and grace,” says Bob Mintzer, a University of Southern California jazz studies professor who’s also a Grammy-winning saxophonist, composer and arranger, and co-founder of the Yellowjackets. “He delivered every song with finesse, control and intense emotion. Every detail was considered, most strikingly the setting for the songs he sang.”

In Philadelphia, radio DJ Sid Mark has hosted a Sinatra-and-only-Sinatra programme on the air without interruption, astonishingly, since 1957. Promos that run during his Sundays with Sinatra show play up the familial eternalness of Sinatra, by turns cocky with the world on a string and soulfully communicating a depth of despair, in the wee small hours of the morning. “Your grandfather listened, your mother listened,” a smooth female radio voice reminds you. “And now you listen.”

I do. And I do partly because my father did before me, and I can’t listen to Sinatra without thinking about him. He was lucky enough to see shows with my mother at the 500 Club, the Skinny D’Amato-owned nightclub back when Atlantic City was riding high.

That’s Life and My Way on the jukebox in dark bars in the afternoon; cruising around in his Chrysler LeBaron with Sinatra at the Sands, the Basie band swinging hard, cranked up on the cassette deck; those are some of my strongest memories of my father.

Sinatra was a master, among other things, of middle-aged male sentimentality. So many of the great saloon songs - Angel Eyes, One for My Baby - are imbued with regret, considering what has been lost while gazing into the bottom of a glass. Sometimes, the singer looks back with a wilful optimism, reassuring himself It Was a Very Good Year, but there’s always darkness lurking.

My dad’s been gone since 1990, almost 25 years now. If I had a musical time machine, I wouldn’t put myself back in some epic four-hour Springsteen show or see any of the acts that were gone before I could catch them, like Jimi Hendrix or Bob Marley. (Howlin’ Wolf would be on the top of that wish list.)

Instead, I’d be back for a second time around at the Superstar Theatre at Resorts, to see Sinatra take the stage with a kick in his step, in a tux, with a big band blaring behind him, opening, as I remember it, with You Make Me Feel So Young. I’d be listening closely, but my attention wouldn’t be fixed on the silver-haired Chairman of the Board. I’d be looking at the smile on my father’s face.

Tribune News Service

His way: celebrate the centenary of Sinatra’s birth with these five classics from Ol’ Blue Eyes

Theme from New York, New York

I've Got You Under My Skin

One For My Baby (One More For The Road)

Something stupid

My Way