What to see in Nanjing, and why now is an appropriate time to explore China’s former capital

The Chinese capital under the Ming dynasty, and after the 1912 revolution, Nanjing has a rich heritage to explore, a moving monument to 1937 Japanese massacre, and tranquil, tree-lined streets for relaxation

This year marks both the 80th anniversary of the Nanking massacre and the 175th anniversary of the Treaty of Nanking, which formally ceded Hong Kong Island to Britain. This historical city on the Yangtze River is about a couple of hours away from Hong Kong, and easily accessible via inexpensive flights, so it’s an apt time to plan a trip to the former capital of China and sample its cultural treats.

Now known as Nanjing, the city’s rich heritage stretches back long before the opium wars. It was first known as Nanking when Zhu Yuanzhang, the first emperor of the Ming dynasty, selected the city as China’s capital in 1367 and ordered the construction of 35km of city walls to protect him and his subjects.

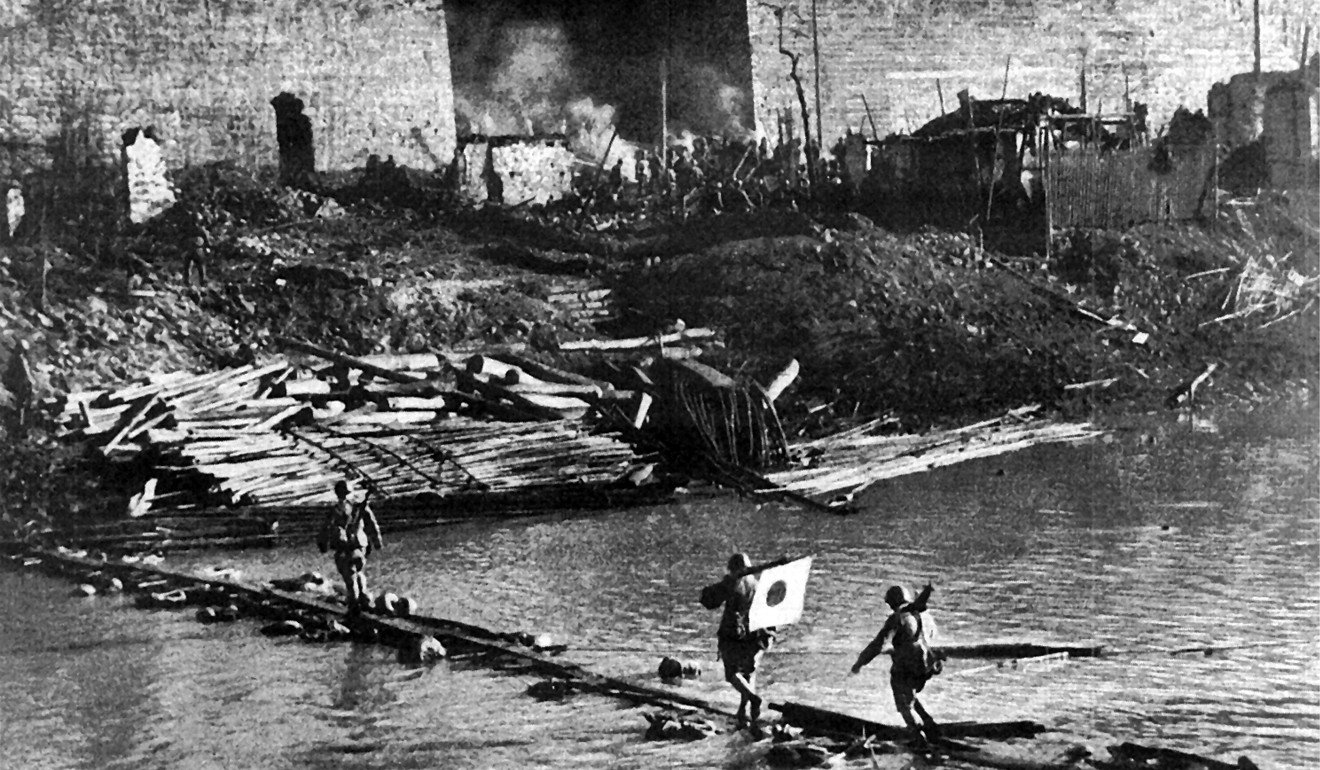

When Chiang Kai-shek established his capital in Nanking in 1927 there followed 10 years of relative stability and prosperity in China, known as the “Nanking decade”. It was abruptly terminated by the Sino-Japanese war, which inflicted a ghastly human toll on China and on Nanking in particular. Between mid-December 1937 and the end of January 1938, some 300,000 residents died and many more were subject to atrocities at the hands of the occupying Imperial Japanese Army.

Given its political significance, it’s delightfully understated. Visitors can see Chiang’s office on the second floor of the Zichao Building, but it’s preferable to wander around aimlessly and enjoy the boating pools, carp ponds, pagodas, halls, stone boats and bamboo gardens and take a rest in the shade of ancient trees.

The grey villas were originally residences for senior government officials and they have been adapted for tourism and leisure.

To sit in the tranquil shade of tall trees in the middle of a busy city and gather your thoughts while sipping a cold drink at the May craft beer and coffee shop is extremely refreshing. There is also a nightclub, Thai massage centre, coffee shops and several Western-style restaurants.

At one establishment, called James Bar (1912 Downtown, Nanjing), guests are requested to place a pin in a map of the world mounted on the wall of the bar to indicate their hometown. Mine was the only one placed in Hong Kong.

The hotel is private and has an opulent air, but the public can wander about under the maple trees and immerse themselves in 1930s republican China, as long as they don’t disturb the guests. Project manager Laughing Tu says the hotel is new but the 26 suites and rooms are already fully booked most weekends and the hotel has won a Unesco award.

There is no bar, but the two high-end restaurants (one Chinese and one French) are both open to non-residents.

The temple has been destroyed and rebuilt several times (most recently in 1984) and the scenic area is on the banks of the Qinhuai River. Boat trips are popular with selfie-obsessed tourists but don’t tend to stray far from the banks.

The temple area is also a perfect location to sample local cuisine from market stalls and the many restaurants. Neither English nor Cantonese is spoken anywhere outside the large Western-style hotels, so this can be an error-prone process of pointing and smiling for those who don’t speak Putonghua. Fortunately, it’s so cheap the occasional culinary mishap (mistaking raw duck tongue on a stick for satay in my case) does not break the bank.

Getting there

China Eastern, Cathay Dragon and Hong Kong Airlines all offer direct flights from Hong Kong to Nanjing, which take two hours and 20 minutes. Once there, the heritage sites of Nanjing are reached via a modern metro system and a cheap and strictly regulated taxi service. If you prefer walking, the major streets are lined with mature trees, much as they were in the Ming dynasty.