Zhoushan, the Chinese island that was very nearly Hong Kong, hasn’t forgotten the opium war

Six months before the British flag was planted in Hong Kong during the first opium war, British forces took Zhoushan. While few in the West remember the details of that conflict in eastern China, Zhoushan hasn’t forgotten

When British diplomat Sir George Staunton arrived in Zhoushan (or Chusan as it was known in the West) aboard warship HMS Lion in 1793, he warmly described the island’s main harbour town of Dinghai as comparable to Venice.

He was not alone in his admiration. The East India Company had first tried to establish a British trading base in Zhoushan in 1700, and for the next 150 years, the British eagerly continued the effort, long before anyone considered the merits of Hong Kong.

Today, as my bus speeds past the smog-shrouded forest of chimneys and cooling towers that make up Ningbo’s industrialised eastern suburbs, en route to modern-day Zhoushan, it is difficult to share their enthusiasm.

“Dinghai nowadays is becoming more a city of shopping malls and skyscrapers – no Hong Kong, certainly, but no boondocks either,” says Liam D’Arcy-Brown, author of Chusan, a detailed history of European interest in the island published in 2012. Brown has kindly offered some guidance for the trip.

As the smog clears and the city of Dinghai comes into view in weak sunshine, it is easier to understand the attraction. The town’s picturesque harbour offered British ships a well-protected deep-water anchorage, and an easily defended settlement in proximity to key trading centres in the Yangtze valley for much-coveted tea, porcelain and silk.

Today, the harbour is studded with dozens of modern merchant ships and narrow river boats, which cluster around the sleepy civil passenger terminal. It is hard to imagine that during the 1840s there were some 5,000 Europeans living in this area.

“There’s very little evidence of the British presence left, sadly,” Brown says. There are, however, still a few traces if you look carefully enough.

On July 5, 1840, during the first opium war, HMS Wellesley launched its first devastating broadside into this waterfront area of Dinghai, having issued a cursory ultimatum to General Zhang Chaofa. The battle lasted little more seven minutes as residents fled for neighbouring Ningbo.

Troops under the command of Captain Charles Elliot landed and scaled a nearby rocky mount, which they called Joss House Hill.

Where a white People’s Liberation Army (PLA) coastguard station now stands, British forces celebrated obtaining their first possession in China, more than six months before the flag was raised at Possession Point on Hong Kong Island – the area where British forces took formal possession of Hong Kong.

As Brown explains in his book, when British Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston learned that Captain Elliot later withdrew from Zhoushan and agreed with the Qing authorities to swap the island for Hong Kong, he was livid. Elliot was promptly replaced by Sir Henry Pottinger, who ordered the military re-occupation of Zhoushan in September that year.

The details of the opium war in eastern China are largely forgotten in the West but not, it seems, in Zhoushan, where there is an immaculately maintained Opium War Ruins Park commemorating its impact on the city.

The park is on the picturesque wooded slopes of Xiaozhu Mountain to the west of the old port. In 1841 this area was a battlefield, a defending Chinese force of some 5,800 troops having dug themselves in. After six days of fighting the British 49th Regiment of Foot, also known as the Hertfordshires, were victorious, and pitched its tents; the area became known as 49th Hill.

Within the park, by the side of the granite steps that ascend the hill, the graves of some of the Chinese troops who died in the fighting have been restored and dot the bluebell-strewn slopes.

The three Chinese generals – Ge Yunfei, Wang Xipeng and Zheng Guohong – who died are commemorated in a memorial hall nearby. The spot where General Zheng fell in battle is marked near the gates of an old Buddhist temple complex.

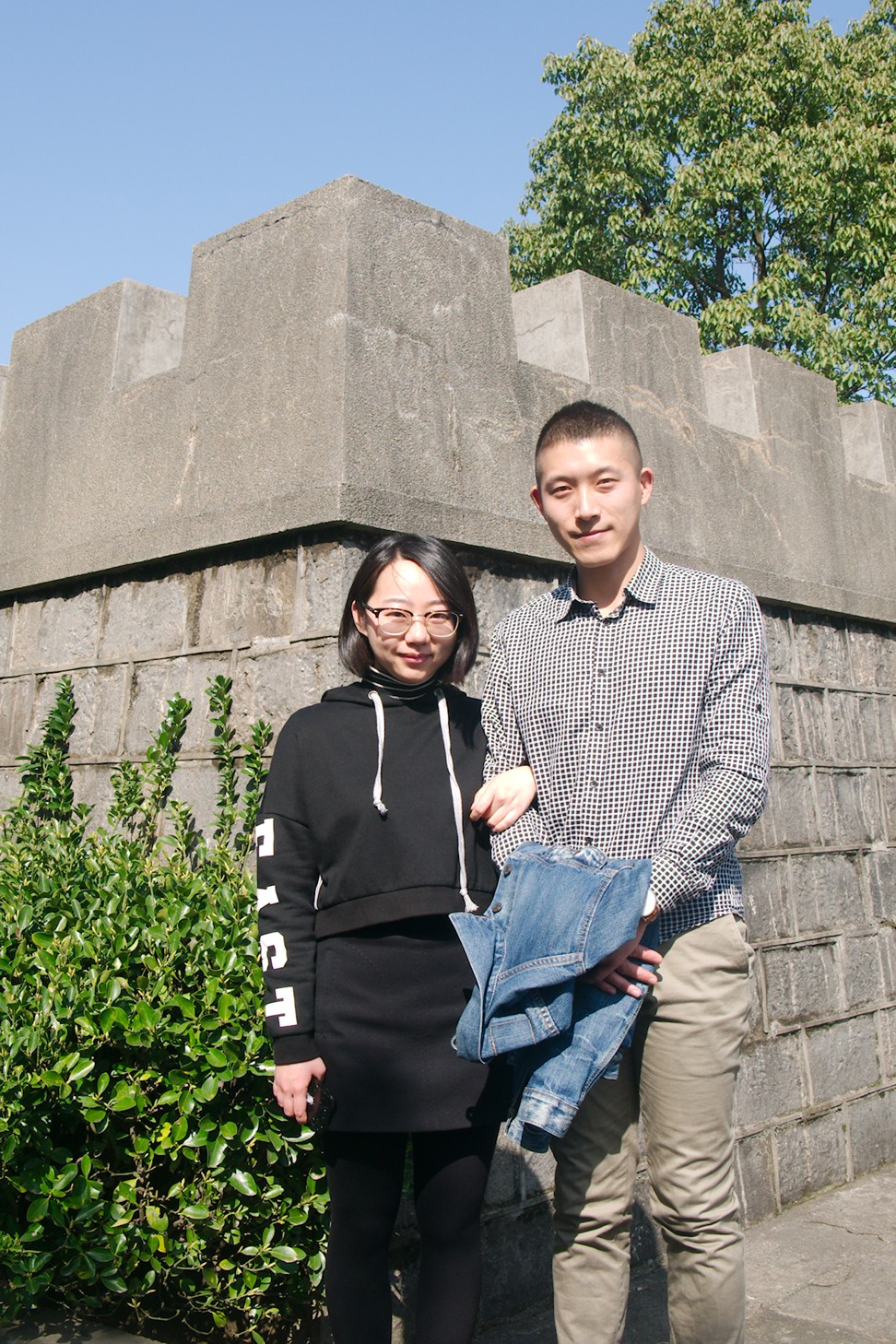

“There are one million people in Zhoushan and every one of them knows about the opium war,” says local businessman Han Xue when asked about the history of Zhoushan as he walks with his wife through the park.

Han asks where I am from and if I know anything about what he refers to as the drugs war. However, when I explain my British ancestry, and ask him about the historical link between Zhoushan and Hong Kong, he offers no further comment.

“Forgetting history means betrayal,” warns a panel at the park’s small museum, near the summit of the hill. Among the exhibits and drawings on display are some British cannons and the uniform of a 19th-century British army officer. At the museum’s entrance, a group of local schoolboys read about Zhoushan’s bloody history.

“What is your feeling when entering the Dinghai ancient battlefield ruins of opium war or standing in front of the anti-British soldier memorial tombs?” asks the panel. It then explains that this is where the first gunfire of the opium war occurred in 1840, an event that marked “the start of modern Chinese history”.

The schoolboys greet me in stilted English, but despite my attempts to question them in both English and Mandarin, they too shake their heads blankly at any reference to Hong Kong.

The terrace outside the museum offers a wonderful panorama over the spring blossom to the harbour below. Given the history lesson available inside, perhaps it is no accident that there is now a PLA naval base in the western harbour, where a ghostly grey frigate is berthed.

It is a delightful stroll along the peaceful, tree-shaded paths of the park on a sunny spring day. But walking east, back to the town centre, it is evident that the waterfront area has experienced a different fate from that of Hong Kong.

There is a noticeable absence of high-rise blocks of luxury flats, international banking headquarters or opulent shopping malls. Traditional shop houses sell nothing more glamorous than shackles, steel wire rope and industrial batteries, and the aroma of noodles, dumplings and samsa (a hot pastry envelope containing lamb and vegetables) emanates from the popular Xinjiang restaurants.

If Britain had not handed Zhoushan back to China and withdrawn its troops in July 1846, it might have been a very different scene. The island was retained only as a guarantor of Chinese compliance with the terms of the Treaty of Nanjing.

Many, like Benjamin Waterhouse – the agent for the British trading company Jardine Matheson on the island – lobbied the British government that if maintained as a free port, “nothing could prevent Chusan from becoming an emporium of the first magnitude”. Britain, however, kept its word and returned it.

The old city was about 1.5 kilometres inland – where the modern city centre now stands – but the old walls have long since been demolished, and the site of the old southern gate is now occupied by a Kentucky Fried Chicken outlet. A few old streets remain, and visitors can walk along the banks of the canals which enthused Staunton in the 18th century. They have not been manicured like the heritage districts of Ningbo and remain scruffy and authentic.

The steps that ascend Joss House Hill behind the old port are no longer accessible, but there is a concrete road which runs up from the western side near a row of seafood restaurants.

In front of an old stone wall is a curious stone monument with an inscription in Chinese. It is a monument to the British 55th Regiment, dedicated to the 430 soldiers of that regiment who died in Zhoushan between 1841 and 1844.

Only a handful of the regiment survived to tell the tale, and the stone was originally erected in the British cemetery to the west of the hill, which is now a construction site. The monument is the only surviving British funerary monument in China outside Hong Kong or Macau, Brown says.

The footprint of Imperial Britain, which made such a huge impact on Hong Kong, can still be traced on Britain’s first Chinese island. Locally, however, it is not a cause for much celebration.

Getting there: Hong Kong Express and Cathay Dragon offer direct flights to Ningbo (about 2 hours and 15 minutes from Hong Kong). An express bus service (about one hour) runs every 10 minutes from Ningbo South bus station to Zhoushan.