Hong Kong district history: Yau Ma Tei, frenetic 24/7 urban centre that’s unlike anywhere else in the city

A neighbourhood seething with energy by day and night, Yau Ma Tei has resisted gentrification and remains after dark the haunt of hawkers, street performers and prostitutes, as it has been for decades

The news came on the 16th of April: insurgents were planning an attack on Yau Ma Tei. The plan was to load up two junks with guns and men, then sneak them up to the shore under the cover of darkness. From there, the men would sink a police boat, attack the Yau Ma Tei Police Station and fire at the buildings along the shore.

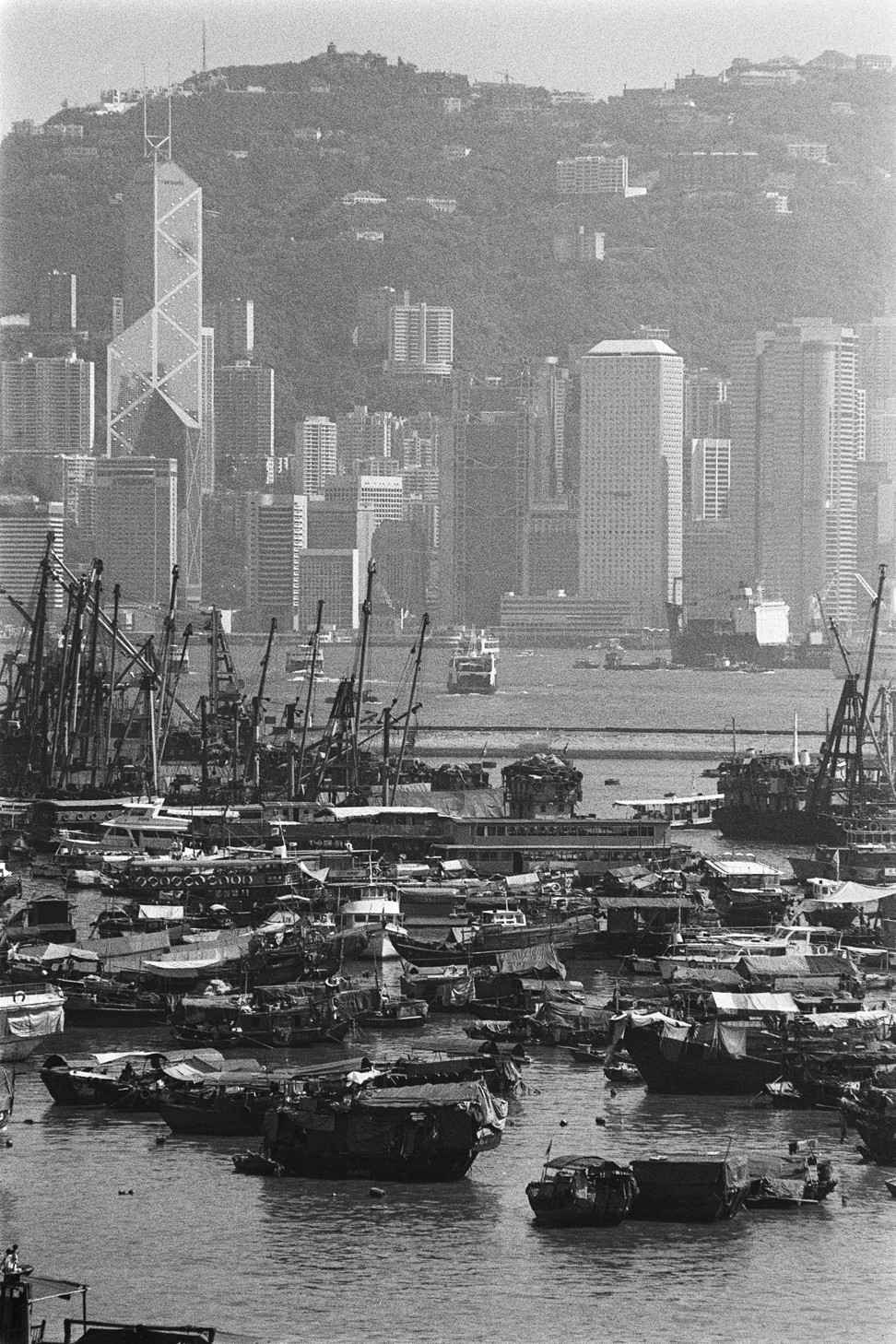

“This was a daring plan, but one which could well have succeeded – cargo junks in large numbers came into Yau Ma Tei at every hour of the day and night, and there were no controls on them,” writes historian Patrick Hase in The Six Day War of 1899: Hong Kong in The Age of Imperialism.

Alarmed, the governor sent 100 men from the Hong Kong Volunteer Corps to defend the neighbourhood. The night passed without incident. The insurgents – New Territories villagers who were resisting the imposition of British rule in 1898 – had decided to abort their attack.

Yau Ma Tei has changed so much since then it can be hard to wrap your mind around this episode. The shoreline has moved a kilometre to the west to accommodate railway lines, motorways and a “spaghetti junction” interchange.

But the police station is still there, albeit a slightly newer version built in 1922 one block to the west, at the corner of Canton Road and Public Square Street. Today it stands empty – the police have moved yet again – waiting for the next chapter in its life.

There’s nowhere in Hong Kong quite like Yau Ma Tei. It seethes with energy at all hours of the day.

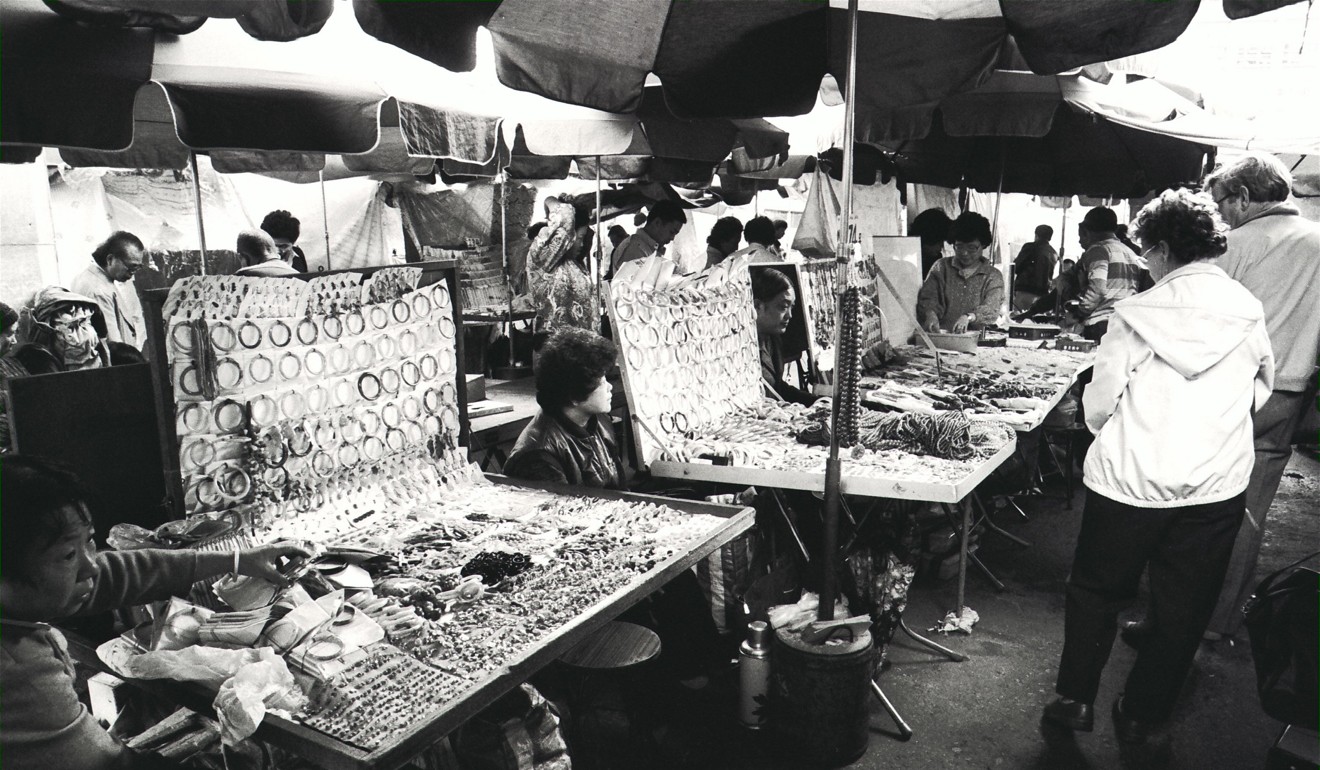

When the vegetable hawkers, jade vendors and chopping board manufacturers close for the day, they are replaced by claypot rice cooks, street prostitutes, warbling karaoke singers and tattooed, bare-chested workers in the Gwo Laan fruit market.

And though Yau Ma Tei is a central neighbourhood, sandwiched between the tourist haunts of Tsim Sha Tsui and the shopping arcades of Mong Kok, it has somehow resisted the redevelopment and gentrification that has made other Hong Kong neighbourhoods feel increasingly similar.

Yau Ma Tei was once defined by a rough landscape of sharp hills and steep ravines. Early Cantonese-speaking inhabitants were joined in the late Ming dynasty by Hakka migrants who quarried granite, made charcoal and worked as blacksmiths or barbers in Cantonese villages.

Unlike the rocky shore found in many other parts of Kowloon, Yau Ma Tei’s shoreline was a soft crescent of sand, which attracted Teochew boatpeople known as Hoklos, who lived just offshore.

A historical account published in The China Review in 1880 describes them as “specially addicted to smuggling and piracy” and “dreaded on account of their ferocious and daring deeds”.

Early settlement of Yau Ma Tei was concentrated in a lush river valley known as Kwun Chung, which covered the area to the south of present-day Jordan Road. This is where Qing dynasty official Lin Tse-hu built a fort in the early 19th century to fend off British advances on Kowloon – which it did successfully, at least until 1860, when a faraway treaty ceded the peninsula to Britain in perpetuity.

Half a century later, the fort and the hill on which it stood were both razed to build a typhoon shelter along the Yau Ma Tei shore.

Kowloon developed quickly in the first two decades of colonial rule. Yau Ma Tei was the focus for much of this new development, thanks to its accessible shoreline, and most of the early landowners were members of Hong Kong’s large Portuguese community, who served as middlemen between the Chinese and the British.

Two businessmen named Delfino Noronha and Marcos Calisto do Rozario built a house on a five-acre beachfront site in the early 1870s, with trees imported from Australia and pineapple trees tended to by Noronha, who was a keen horticulturist.

Noronha soon established a ferry service between Yau Ma Tei and Central, the predecessor to the Hongkong and Yaumati Ferry Company, which still exists today.

The police station was built along the shore in 1873 and the street on which it stood was named Station Street. A postcard from 1910 shows a particularly bucolic scene, with the pitched-roof police outpost hidden behind a grove of palms and other trees; in the foreground, men dressed in loose Tang suits walk barefoot along the beach.

As Yau Ma Tei developed, it drew more Chinese residents from surrounding villages. The area’s focus shifted from Kwun Chung upshore to the area around the police station, to the point where the local Tin Hau Temple was relocated to Station Street in 1876.

By 1880, there was a match factory, a preserved ginger factory and a “considerable Chinese junk trade” in Yau Ma Tei, according to the 1900 book European Settlements in the Far East.

The push and pull of the tides defined life in Yau Ma Tei. In fact, its name likely refers to the oil and hemp used by fisherman and Tanka boatpeople to repair their vessels. But the sea was also a world apart from the settlement onshore.

After the typhoon shelter opened in 1915, thousands of Tanka created a floating village of sampans that served as restaurants, markets, brothels, casinos and opium dens.

When criminals from Yau Ma Tei began escaping from police by hiding inside hawkers’ sampans, police banned hawking in the typhoon shelter after 9pm, eliciting protests from the boatpeople. They eventually reached a compromise: the markets would close at midnight.

Things weren’t any more orderly inland. Station Street – renamed Shanghai Street in 1909 – had become the heart of a thriving commercial district. After dark, hawkers flocked to Temple Street, which had become a night market after the second world war.

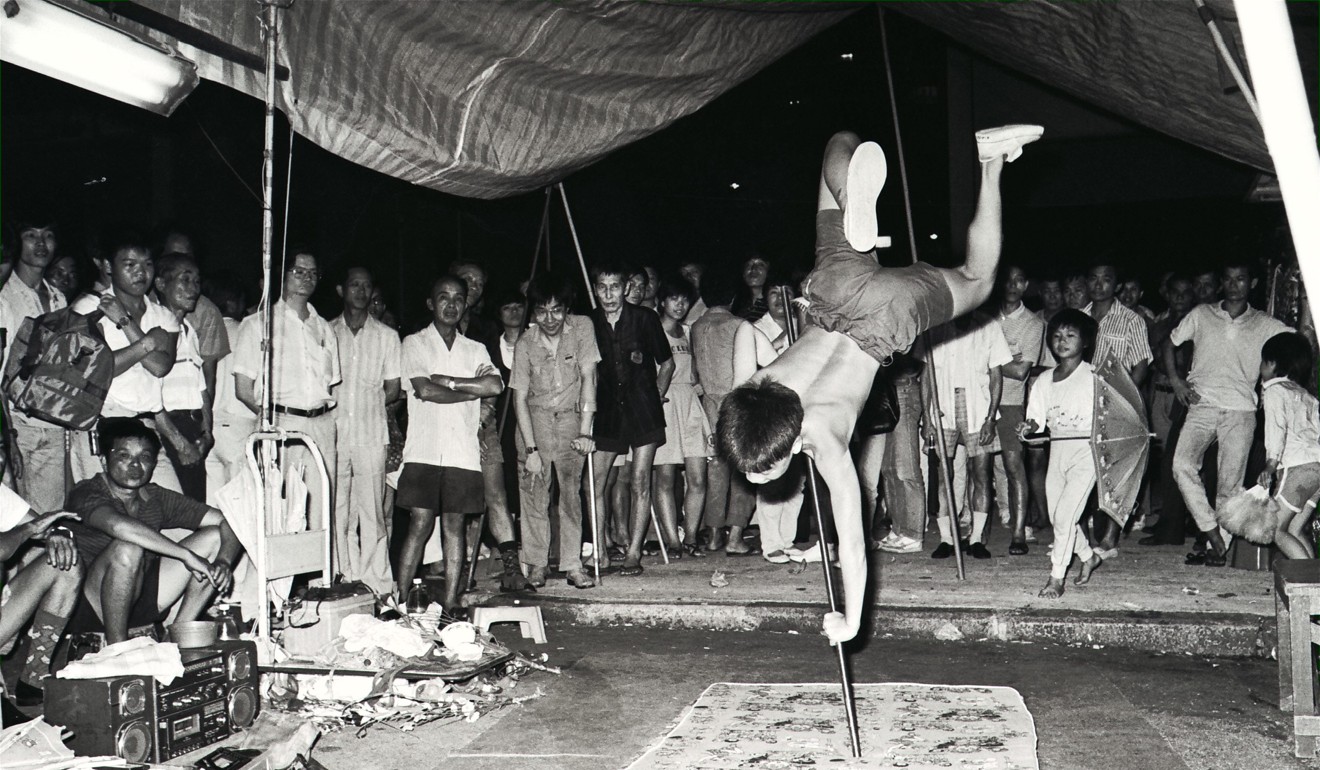

“Temple Street was full of weird stalls performing teeth extraction, snake dances, fortune telling by a bird and so on,” recalled Chan Kwong-yu, owner of the Tai On Coffee and Tea Shop, who shared his life story with the HK Memory oral history project.

Women gathered to sell dessert soup they had made at home and a hawker was famous for his HK$1 pieces of fried chicken. “People suspected it was made with dead chickens from the poultry market on Jordan Road,” said Chan.

In 1975, the Post ran a feature about Temple Street – referring to it as “Sin Street”, a place where Kowloon’s working class came to entertain themselves after dark. Reporter Neil Perera described the scene in front of the Tin Hau Temple.

“As dusk settles on the square, canopied by brooding banyan trees, the area comes alive with gaiety,” he wrote. “A three-piece band positioned at the entrance to the temple blares away until late at night. A few feet away, more people gather around a temporary food stall, savouring bowls of steaming hot noodles, while others cluster around a television set perched on a wooden structure.

“In the midst of it all, and mingling freely with the populace, are the pimps, thugs, drug pushers, pickpockets and devious characters of every description.”

The police station stood watch nearby – but not necessarily as a beacon of protection. Until the 1970s, Hong Kong’s police force was notoriously corrupt, and constables who patrolled Yau Ma Tei demanded all kinds of favours. Dai pai dong workers delivered them lunch and dinner with no expectation of being paid.

Many news clips relating to the station in the early 20th century speak to a tumultuous relationship between the police and the citizenry. On the evening of March 17, 1922, an “angry mob” attacked the police station after an Indian constable was accused of stealing fruit from a hawker and beating him when confronted.

In 1929, a labourer was arrested after plastering the station with anti-colonial propaganda.

Things changed after the 1970s, when a corruption crackdown ended the culture of bribes and favours. Now the police station awaits a new use, far from the shore on which it once stood. But the Temple Street market lives on, as do the hawkers, the street performers and the pimps – reminders of how, for all the ways it has changed, Yau Ma Tei’s essential character remains intact.