Taking care of ‘family’: how small tourism businesses in Bali, Phuket and Nepal are lending a helping hand amid the Covid-19 pandemic, from paying medical bills to distributing food

- A sherpa’s big plans to revive tourism in his Nepalese hometown stalled amid the pandemic, but he’s created paid work for neighbours and funded medical care

- In Bali, a hotelier couple kept staff on the payroll despite their resort’s closure, while in Phuket businesses joined forces to distribute food to the needy

Almost everyone has felt the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on their lives in one way or another. Some of us bemoan dining and travel restrictions, but those in developing countries that were heavily dependent on tourism are in more dire straits.

Even as a trickle of tourists begins to return, many in their destinations are in debt or going hungry. While big hospitality brands have made it part of their corporate social responsibility and public relations to help their staff – and in some cases, local communities – owners of small tourism-related businesses have been doing the same, only without the fanfare.

Solukhumbu, Nepal

When the pandemic hit, Ang Tshering Lama’s first priority was to keep paying his staff. Fortunately, many future guests of his lodge – Happy House, in Phaplu, Solukhumbu, in eastern Nepal, which has played host to legendary mountaineers such as Italy’s Count Guido Monzino and New Zealand’s Sir Edmund Hillary – didn’t cancel their bookings and allowed Ang to keep the deposits to give his staff partial salaries. Throughout the pandemic, the 32-year-old has not drawn a salary for himself.

To escape political turmoil in Nepal, Ang’s family sought asylum in the United States in 2001. He returned in 2014 with the aim of bringing tourism back to the Phaplu Valley – a stop on the Everest trail before Lukla Airport was opened, in 1964 – with Beyul Experiences, an expedition company he founded, and Happy House, which his grandfather built in 1971. For the refurbishment of the latter, Ang borrowed money.

“Before the pandemic, I was hoping to repay the loan within two years,” says Ang, who adds that Happy House was doing well when it reopened in 2018. The following year, the lodge made it into Condé Nast Traveler’s Gold List.

Before the borders closed Ang, a keen biker, had wanted to train youths in Solukhumbu to be mountain-bike guides, to give them an alternative to jobs as porters on climbs up Everest or construction workers overseas.

When tourists stopped coming, he threw himself into the construction of a pump track – a circuit of rollers and banked turns for cyclists – on land belonging to a great uncle, with money raised with the Himalayan Trust and from auctioning stays at Happy House.

The new track caught the attention of the local government, which enlisted Ang to build a mountain biking trail partially funded by the United Nations Development Programme. For this project, about 30 locals were hired.

“We cannot ask them to volunteer as they haven’t had income for two years now,” says Ang, who works on a voluntary basis himself.

Another project Ang helped raise funds for and operate was a pop-up medical camp in eastern Nepal’s Sankhuwasabha district.

Knowing that many villagers would not have had access to a proper hospital, a group of medical staff, including the retired Mingmar Sherpa, the first Sherpa doctor to become director general of health for Nepal, journeyed to remote Chichila village, to set up the camp. Over three days in November 2020, 417 people who had not received medical attention for many months turned up.

Raju Ghimire, 40, of Paphlu, has been another beneficiary of Ang’s largesse. As the country readied for the Visit Nepal 2020 promotion campaign, Ghimire – like many others – invested in a small business venture to capitalise on the expected influx of visitors; the 1.2 million who came in 2019 had raised hopes that the target for 2020, 2 million, would be attainable.

Others bought or established tea-houses, while Ghimire bought a car and set himself up as a self-employed driver.

When his mother was admitted to hospital with Covid-19 in May, the family’s savings were used to pay part of the medical bills. For the remainder, they took out a loan. Ghimire also has a loan on his car, which he is servicing at an annual rate of 13 per cent.

Nepal’s interest rates for personal loans are infamously high – Ghimire is also paying 24 per cent on the loan taken out for his mother’s medical care – and then there are the monthly repayments. His family of seven, including three children between the ages of five and 12, and his parents, live a hand-to-mouth existence on the little he has left after paying his bills.

Their outgoings would be all the greater if Ang hadn’t given a Ghimire – an old acquaintance – money towards the medical bills.

Asked if he is worried about the future of his own businesses, Ang refers to Tibetan Buddhism’s Wheel of Life: “Nothing is permanent.”

Bali, Indonesia

In Bali the pre-pandemic crowds have gone, as have “75 per cent of the businesses”, according to Singaporean Sean Lee, an entrepreneur who helped turn Seminyak’s Jalan Petitenget into a hip enclave with the now-defunct Hu’u Bar 20 years ago.

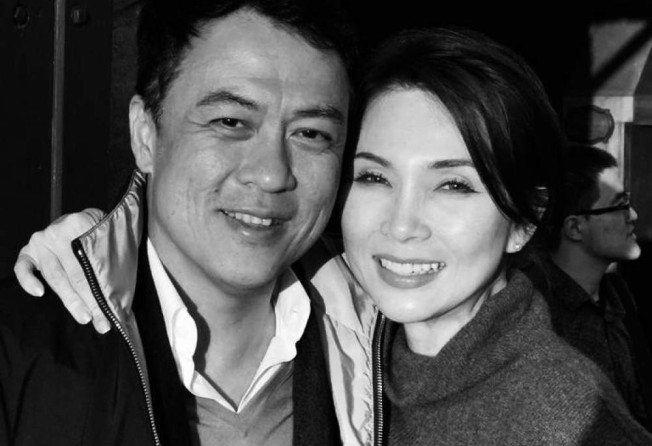

Luxury beach resort Soori Bali is not among those that shut, but its Singapore-based owners haven’t been able to visit since early 2020. Nevertheless, architect Chan Soo Khian and Ling Fu, a handbag designer, have continued to take care of the 190 staff they employ, as well as the other 3,000 or so people who call the village of Kelating, which surrounds their resort, home.

Soori Bali, 30km (18.6 miles) to the northwest of Kuta, was closed from March to December 2020 but all staff kept their jobs, the Soori Relief Fund having been set up to pay partial salaries.

“While staff like security, and those who are deployed to build the prototype of Tenda [Chan’s sustainable model for accommodation, being built on land around Soori Bali] are working, many of the staff are not,” says Greg Hoehn, the resort’s general manager, citing low occupancy even after reopening.

Not that the other staff haven’t been given tasks to fulfil; under the owners’ direction, they have set up the Soori Green Council to organise regular clean-ups of Kelating beach by the villagers. Collected rubbish is exchanged for rice.

Of the recent reopening of Bali’s airport to international flights from certain countries, Hoehn says: “It is a small step in the right direction – the current signs are definitely more optimistic than a couple of months ago – but it will take much longer for the tourism industry to recover. While talking to my peers in Bali, we all agree that in order to help the local community, tourism must return.”

In the meantime, beyond Kelating, Soori Bali supports the Yayasan Gayatri Widya Mandala orphanage with donations of cash and food, and for the resort owners there is no question that they should keep helping the people of the village. As far as Chan is concerned, he is simply taking care of “family”.

Phuket, Thailand

Under the glare of the afternoon sun, Patong beach is a golden expanse – a picture of serenity and a far cry from how locals remember it in peak season. Just 18 months ago, it was buzzing with sunbathing tourists and hawkers peddling souvenirs and massages. Now, you’ll “see only one shop out of a thousand open”, says Australian Andrea Edwards, a resident of Phuket since 2017.

It was on one of Phuket’s empty streets that Shaun Stenning, owner of 5 Star Marine, a provider of VIP speedboat transfers, and his staff found Surat Saengmani, 86, who had been living beneath a tarpaulin for six weeks after his family abandoned him and left Phuket to fend for themselves.

“He was in a bad shape,” says Stenning, an Australian who has been living in Phuket for 15 years. In just two months – June and July 2020 – about 50,000 of the out-of-towners who made up much of the island’s population left Phuket, says Stenning. “They had no work, and therefore no food.”

Unlike Bali and Solukhumbu, where the locals can at least plant crops, the people of Phuket have neither the skills nor the arable land to grow enough of their own food. As early as March 2020, Stenning was buying supplies and distributing them with his staff.

With the shelters all full, Surat Saengmani is still on the streets, but he is at least now being served cooked food.

With 90 per cent of Phuket’s economy dependent on tourism, the need for relief is great. And among those suffering the most are the many foreign construction workers who have been living in makeshift tin-shed villages since the pandemic struck.

Wanting to pull resources together to help as many people as possible, Edwards rallied everyone she knew who had been feeding the needy on their own, including Stenning. Umbrella organisation One Phuket was established in January.

One Phuket’s main activity is to distribute Life Bags, each of which contains essentials such as rice, tinned sardines and cooking oil, and should last a family of four for four days.

The list of people who have helped (or rallied their staff to help) with buying, packing and distributing the Life Bags runs into the hundreds, says Edwards, and includes Scott Toon, the managing director of The Pavilions Hotels and Resorts (owned by Hong Kong-based lawyer Gordon Oldham) and Nando Borralho, owner of martial-arts studio Sutai Muay Thai.

On the ground, operations are led by one of Stenning’s local staff, who prefers to be known as Khun Zeera, and the Australian estimates that by early October, 360,000 Life Bags had been distributed.

With demand having spread beyond Phuket to outlying islands such as Koh Lipe and Coconut Island, where Super Life Bags – containing larger quantities, designed to last weeks – are distributed, and a full recovery is not expected any time soon despite the reopening of Thai borders to vaccinated travellers, it seems likely many more Life Bags will be needed yet.