Hong Kong's Mentally Ill Suffocated by Stigma and Red Tape

Community mental health centers are caught in a broken system—they’ve got the government's money, but not its space.

At an office tucked away in a shopping mall a stone’s throw away from the mainland, 12 social workers cram themselves into what looks like a 24-hour call center. The door has no sign and gray cubicles suffocate a narrow space.

But this is no threadbare non-profit organization. It’s a government-funded team responsible for supporting the mental health of some 300,000 residents of Hong Kong’s North District, covering areas including Sheung Shui, Fanling and villages around the border.

Because the shopping mall where the team's office is located is zoned for industrial use, like many shopping malls in Hong Kong, government-funded counseling services are not allowed. The government's Land Use Department strictly prohibits it. Instead, the social workers meet “service users”—that’s the official term for people with mental illness who make use of the center’s resources—in public spaces, or sometimes they borrow rooms tiny community centers may offer.

But mostly, counseling happens at the local McDonald’s.

The service users most often won’t speak to social workers at home, in fear of being judged by their family members. Without a dedicated space for them, the grease-laden corner of a crowded burger joint is their preferred choice.

Speaking anonymously, one social worker describes the difficult waltz of offering counseling in Hong Kong. In a cramped McDonald’s, she has to find a corner without other customers—and then must sit with her back facing others, to hide the service user. When a service user begins to cry or becomes visibly upset, they get self-conscious and have to move to another table. Sometimes, this happens more than once during a meeting. It’s an everyday struggle to keep their identity and their issues a secret, smack in the middle of the public. And this happens up to five times a day.

The search for a permanent space to provide outpatient support has been ongoing for five years, and there’s no end in sight. “Some of our staff gets frustrated and tired—although there’s hope, they’re curious if there’s really hope,” says Christine Cheuk So-shan, who helms the office.

Center Struggles

Cheuk’s office in North District is one of 24 Integrated Community Centers for Mental Wellness (ICCMWs). Starting from a pilot project in Tin Shui Wai in 2010 and with funding from the Social Welfare Department, an NGO called the Mental Health Association operates centers across Kowloon East and the New Territories.

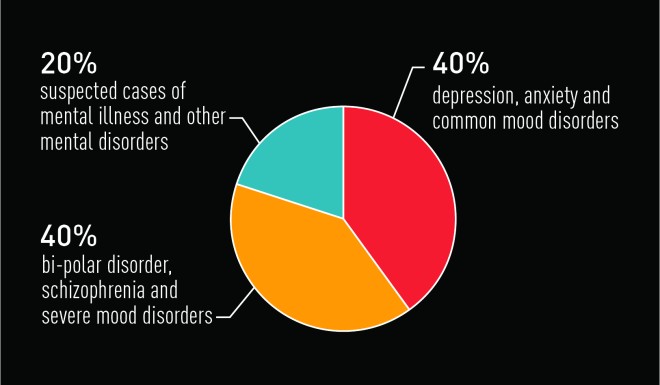

They provide the kind of care that can help those suffering from mental illness to eventually transition back to living in the community. The ICCMWs are set up to offer services to those aged 15 and above who have either been discharged from inpatient psychiatric care or those who may have suspected mental illnesses. The centers are meant to be a one-stop, accessible community support space for voluntary outpatients to recover from mental illness, whether that takes the form of using the gym and internet, meeting with occupational therapists or even just building a network of peers.

For that reason, the ICCMWs are almost always set up in public housing estates.

Surprisingly, money’s not a problem. Cheuk is quick to dismiss the idea that her mental health center is strapped for cash. She says the center has enough financial support from the government and it keeps increasing every year. And these social workers—who work under the Social Welfare Department—are on the same enviable pay scale as the government’s civil servants.

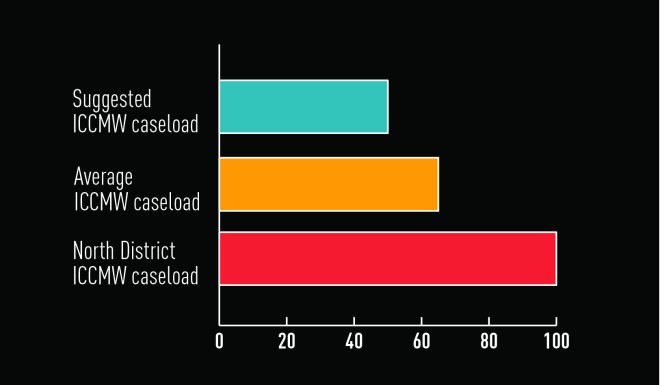

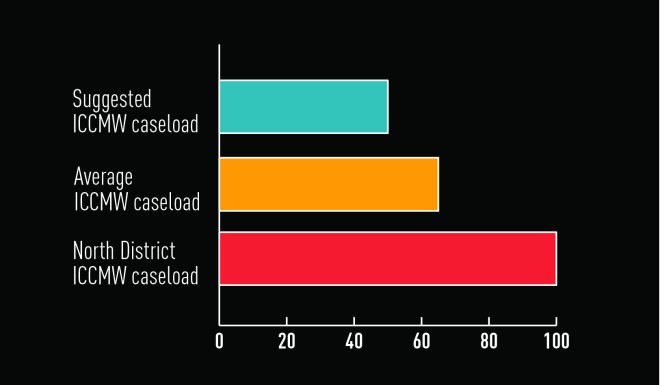

But it’s hard to keep staff because the job is just so hard. A social worker in the North District can have up to 100 cases at any one time—and sometimes it can take an hour to travel to meet someone because of the district’s sprawling size compared with the rest of the compact city. The North District’s caseload is unusually high, too—average caseload across all the districts is 60 to 70 cases for each social worker at a time. The Mental Health Association says a case worker should be dealing with a maximum of 50 cases at a time.

Cheuk says the turnover rate is high and thanks to the stress, the staff leaves about every three months. The team is currently seven short. “The area is so scattered—there are 110 villages in the North District,” says Cheuk. “How can we promote mental health with our manpower?”

Spatial Awareness

The scramble to help service users anywhere they can, from fast-food chains to public parks, isn’t just the case for Cheuk’s people. At the ICCMW in Kwun Tong, occupational therapist Tammy Chan Yuk-tung shares her desk with a colleague and struggles to find enough room to work. Because the center where Chan works is undersized and swamped as it is, she tries to meet service users mostly in nearby sports centers.

She says that while the government is giving the ICCMWs more resources, it’s still failing to give them the most important thing: more space.

The staff in Kwun Tong numbers more than 20, even though the center is designed for 12. The activity rooms and interview rooms are constantly overbooked. “But we’re lucky, indeed, to have a space,” Chan says.

The space—at Lok Wah Estate—is roughly 280 square meters. The contract for government funding says that each center should be some 465 square meters.

“I can’t think of a center that’s 465 square meters right now,” says Ching Chi-kong, the Mental Health Association’s assistant director of service and education.

Five of the 24 centers haven’t been able to secure space in public housing estates: One in Eastern District uses an office in a commercial center and another in Sha Tin works out of a halfway house. In Kowloon City and Tsuen Wan, the ICCMWs use commercial offices to serve the districts, and it’s the same story for North District. All of these spaces are considered temporary, but there’s no telling how long these centers will have to wait for permanent space in a housing estate. In Tsuen Wan, they’ve given up trying.

The lack of a space to network and build connections with the community works contrary to the ICCMWs’ purpose. The intent of voluntary outpatient care is to reintegrate those with mental illnesses into their communities, to be the launch point for living independently. Informal networks are vital so that service users can eventually leave the ICCMWs and support each other without social workers around them.

How can recovery be achieved, then, without space—and why is it so hard to secure in despite the necessity?

Read More: How Stressed Out Is Hong Kong?

Competition Anxiety

“The space issue comes down to competition,” says Dan Yu Kin-sun, the chief officer of service for the ICCMWs. “We’re competing for limited space with services for the elderly, autistic, education and more.”

And the process of setting up shop is anything but easy. In North District, the ICCMW requested to change the use of a space zoned for education—but was denied. And there’s no prospect of a space opening up in public housing anytime soon—there’s already a desperate lack of public housing in North District.

In Kwun Tong, the center’s undersized space was originally a kindergarten—and it wasn’t easy to get. “We had to ask the district councilor, and then we had to have a meeting with residents of the public housing estate where we wanted to operate,” says Yu. “It’s only without opposition at that point in the process that we could get permission to operate.”

The ICCMWs have a budget limited by the government and can only pay up to $45 per square meter of space for a center, the concessionary rate offered by the Housing Authority to non-profits. That’s a dramatically low price for space in land-hungry Hong Kong.

“Service users in these areas without a space can’t even drop in to watch TV or for a birthday party,” says the Mental Health Association’s Ching.

When HK Magazine asked the Social Welfare Department why the ICCMW in Kwun Tong is smaller than the size agreed upon by the government contract, a spokesperson responded: “In order to meet the shortfall of the operating area, the Social Welfare Department has already reserved a premise of around 600 square meters in a redevelopment project in Kwun Tong for service re-provisioning of this ICCMW.”

And when HK Magazine asked if the ICCMWs are understaffed, the spokesperson said: “Under the Lump Sum Grant Subvention System, ICCMWs have the flexibility to deploy the subvention in arranging suitable staffing to ensure service quality to meet service needs.”

Read More: Hong Kong Psychiatrists Still in Low Numbers, Overworked

Difficult Districts

Finding room to breathe isn’t the only challenge facing Cheuk’s ICCMW: North District is a uniquely difficult place to be a social worker. It has a high population of migrants from the mainland, who are prone to experience mood disorders when adjusting to Hong Kong. There are also many villagers living in the district, who have yet to discard the negative stigma attached to mental illness in traditional Chinese society.

“Paramedical professionals are not willing to commit themselves to this sector: It can be quite dangerous,” Cheuk says.

Cheuk recalls an extreme case where a 27-year-old woman had been subjected to regular exorcisms by her mother since she was 11, and forced to drink a potion while incense was burned. Her family thought her body has been taken over by a ghost. In fact, she had severe schizophrenia that went untreated for 16 years.

What makes North District’s prickly relationship with mental illness even more complicated is a widely publicized murder in January 2012, in which a psychiatric patient living in a housing estate in Sheung Shui stabbed a security guard to death. The incident sparked enough paranoia in local residents that they asked Cheuk and the ICCMW to publicize a list of its service users. The ICCMW’s stance was that any breach of confidentiality would be inhumane.

Read More: Leung Choi-ling's Social Enterprise for Mental Illnesses Faces Its End

Stigma Warriors

The battle against the stigma of mental illness is rarely well received in Hong Kong. Those with mental illnesses are a fringe community, largely ignored, sometimes hated and feared.

At the end of last year, Eric Chen Yu-hai, the president of the Hong Kong College of Psychiatrists, decried the Legislative Council for their “inappropriate remarks” towards people with mental illness. “Discriminatory behaviors severely undermine our patients’ self-image, prevent them from seeking proper care and limit their participation in society,” Chen wrote in a letter to Health Secretary Ko Wing-man.

This pervasive discrimination in Hong Kong is why the ICCMWs have a second purpose: to spearhead public education programs. Like most other things, public education doesn’t come easy for the mental health centers. One of the stipulations for government funding requires that each ICCMW organize 450 to 500 public education programs every year—that works out to two per day, in addition to social workers’ existing caseloads. Locating a venue, staffing the program and even finding participants hurls the ICCMWs—particularly those operating without a permanent space—into yet another everyday struggle to stay afloat.

“But we’re flexible,” says Cheuk. “We’re social workers.”

In 2012, the ICCMWs won a rare victory with the support of Cantopop singer and actor Fiona Sit Hoi-kei, who signed on as a mental health ambassador and shared her own story of recovering from depression. The Mental Health Association’s Ching Chi-kong says celebrities like Sit can trigger a pivotal change in the public’s perception of common mental disorders—they can view it more positively and see that recovery is possible.

“It also helps the public understand that someone they know, like Fiona Sit, can develop mental illness,” he says.

A Brighter Side

Is there a solution underpinning the struggle? To overcome stigmatization for the long haul, the Mental Health Association along with the ICCMWs is urging the Hong Kong government to integrate mental health education into the primary and secondary school syllabuses.

With luck, the next generation won’t perceive those with mental illnesses so negatively—and also, they will come to understand better their own challenges with mental illnesses, rather than just ignore the problem.

Better yet, not all communities are working against the ICCMWs. In Tai Po, neither the public nor local leaders were opposed to the district’s mental health center—the community there was happy to have their first easily accessible counseling service. This kind of grassroots acceptance is what the project needs to finally gain wings after an arduous years-long stumble.

With some luck, McDonald’s might go back to just serving up burgers once again.