Failing Grade: Hong Kong Students Can't Stop Paying Cram Kings

Private tutors aren’t just about exams—they’re about a multi-billion-dollar need to keep our kids learning.

Tiffany Yip and Vivian Lee are just like any other 16-year-old girls—except they’re shooting for a spot at a top university. After class ends at the prestigious Maryknoll Convent School, they both go off to cram school. This costs Tiffany $3,000 a month and Vivian up to $5,000. They both see a private tutor, too—another $1,600 every month. Tiffany, who’s talented with music, also takes piano and flute lessons.

Over the next six months, Tiffany will spend $38,400 and Vivian $39,600 on cram schools and extracurricular learning. A full academic year at the city’s most coveted college, The University of Hong Kong, costs only slightly more: $42,100.

Cram schools are big business in Hong Kong—typically an hour at one of these mass-tutorial centers costs $100. And it costs more for the “celebrity tutors,” whose faces we see on billboards and buses. One celebrity tutor, who spoke to HK Magazine on the grounds of anonymity, says that it costs her students $400 to $500 an hour to supplement their English education. But she’s seriously considering a rate hike—after all, she’s been charging the same for three years. Other subjects can run anywhere from $300 to $700.

Read More: Ken Ng Is the King of Cram Schools and Celebrity Tutors

The majority of Hong Kong’s students are paying. A 2012 survey by the Hong Kong Federation of Youth Groups found that more than three-fourths of its student respondents attended a cram school.

“This isn’t a clever way to nurture young talents—we should try to get away from depending on private tutoring,” says education lawmaker Ip Kin-yuen. “This dependency isn’t a good sign.”

But it doesn’t look like that dependency’s changing anytime soon.

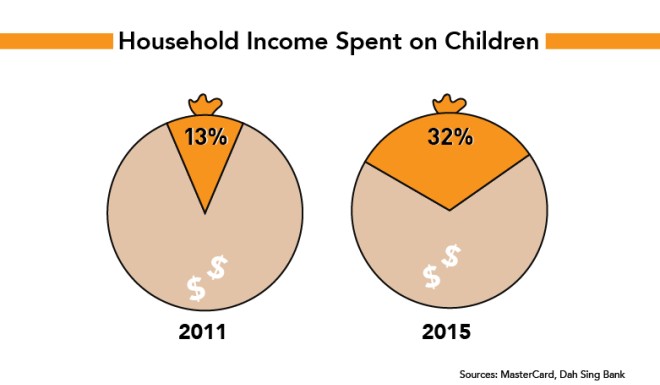

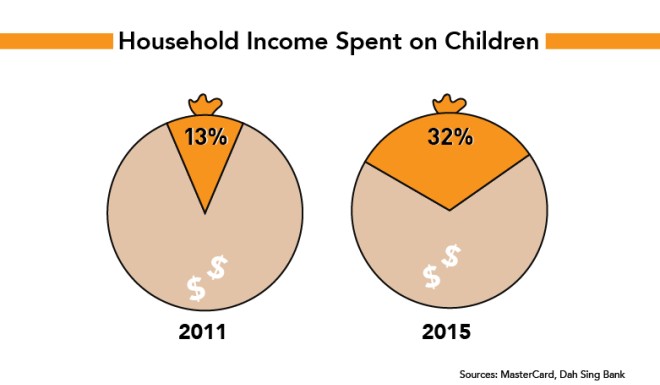

A MasterCard consumer purchasing survey found that in 2015, families spent up to 30 percent of their household income on their children’s education—that includes tuition and extracurricular activities. A survey by Dah Sing Bank last year puts that number slightly higher, at 32 percent. The MasterCard survey shows extracurricular “enrichment classes”—non-cram school lessons—accounted for a large portion of this spending. The most popular classes were music, academic subjects, sports, languages and art.

Only eight percent of parents said that they send their children to extracurricular activities like this because their kids enjoy it.

In Hong Kong, the average working household made $30,000 a month at the end of 2015—that’s not very much if you’ve got a kid to get into university. Say that family has one child and spends 30 percent of their income on private education costs: They lose $9,000 and are left with $21,000 to support a family of three each month.

“The main problem is we’re artificially making entrance to university extremely competitive,” says legislator Fernando Cheung Chiu-hung, a member of the government’s Panel on Education. “Eighteen percent of our youth can get a subsidized university placement and we could easily double that—we’re leaving no space for children and we’re taking away a lot of room for innovation.”

Cheung, also the vice-chairman of the Labour Party, sees little purpose in sinking so much money into Hong Kong’s cram culture.

“This isn’t learning,” he says. “Our children are pushed into a system where they have to go through exercise after exercise, extracurricular activities, exam preparation and all that. Even when kids take up activities in arts and sports, they’re just there to be competitive and put one more thing on their resumes.”