Chinese Typewriters Exist, and Tom Mullaney Wants to Save Them

Yes, they exist. Yes, they're awesome—and they could be coming to Hong Kong

Stanford University professor Tom Mullaney is on a mission to rescue the the Chinese typewriter from the scrap heap. Over the past decade he's built a collection of the underrated machines, and now he's launched a Kickstarter project to bring his collection to museums around the world—Hong Kong included.

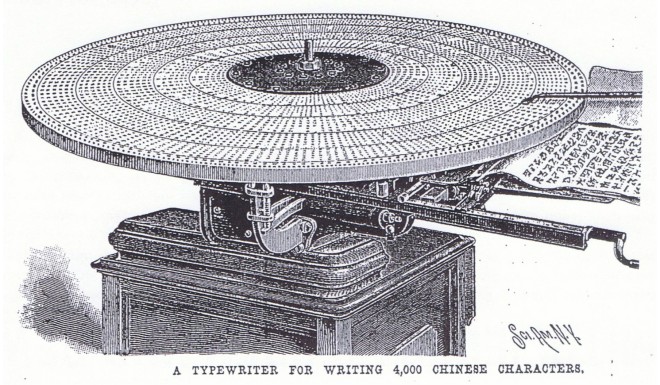

What inspired you to study Chinese typewriters? The Chinese typewriter flies in the face of more than 100 years of conventional wisdom, and so does the history of modern Chinese information technology. When we look at Chinese IT and the Chinese language now, we see a world that many in 1900 considered impossible: A vibrant, modern IT world based on Chinese characters, which are one of the fastest, most widespread, and successful languages of the digital age. This would shock the many people who, for the past two centuries, assumed that such an outcome was conceivable only if China got rid of character-based writing and went the route of wholesale alphabetization. The answer to this outcome can be found by studying the most “seemingly impossible” information technology of all: The Chinese typewriter, an object many thought it would be impossible to build.

So what does the success of the Chinese typewriter mean? I think it calls for a rewrite of the entire history of IT as we know it. In sharp contrast to the popular idea that “winners write history,” in the case of modern Chinese language reform, it is the losers of history who have managed to command the greatest attention of scholars: Historical figures like the famous writer Lu Xun, or co-founder of the CCP Chen Duxiu, who were famous for advocating the abolishment of Chinese characters.

By contrast, we know virtually nothing about the “winners” in this story: The brilliant engineers, linguists, entrepreneurs, and everyday individuals who actually built China’s contemporary information environment. Unlike their celebrated and well-known abolitionist counterparts, the actual builders and users of the modern-day Chinese information infrastructure—now the largest IT market in the world—never appear on undergraduate course syllabi about China. Indeed, they were often anonymous even in their own times. My hope is to tell the story of China’s real iconoclasts.

Why exhibit now? There are literally hundreds of museums dedicated to the history of the Western typewriter and to Western IT, but there is not a single museum dedicated to the Chinese typewriter, or to the history of modern Chinese and East Asian information technology. So, when researching the history of Chinese IT, I had no choice but to build an archive from scratch. This past January, the opening of the “proto-exhibit” at Stanford University was wonderful and very encouraging. The event was full of conversation and curiosity: Despite all of the distortions and misrepresentations of Chinese information technology in pop culture, people are very open and eager to learn about this fascinating chapter in the history of language and technology.

With the “Save the Chinese Typewriter” campaign I just launched on Kickstarter, the goal is to prepare this collection for a “world voyage,” bringing it to museums around the world over the course of five years. In particular, the goal is to make this collection viewable: Not just in major, metropolitan museums with larger budgets, but also smaller community museums that would put this one-of-a-kind collection in front of school children and local communities. I truly believe that the world needs a museum of Chinese typewriting and Chinese IT!

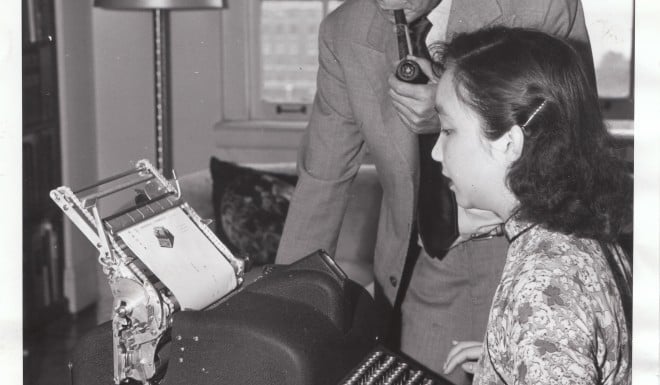

Which piece from your collection are you most proud of, and why? My favorite Chinese typewriter in the collection is still the first one I ever received. The machine came from a Chinese-American Christian church in San Francisco, where it had been used for years to compose the weekly church bulletin. The church was going to throw it away, but someone saved the typewriter until the right person came along.

It felt very good to help save this machine, and to give it a new home. The machine is now on exhibit at Stanford University as part of the proto-exhibit, and will travel with the exhibition around the world. It is a “Double Pigeon” Chinese typewriter produced in mainland China by Shanghai Calculator and Typewriter during China’s Maoist period.

Does the Chinese typewriter get the credit it deserves today? Collecting Chinese and Japanese typewriters has all been an exciting process, no doubt, but also a revealing one: If these had been rare Western typewriters, individuals looking to give away antique typewriters would have enjoyed a wide array of museums where they could have donated these rare artifacts. But because there are no such museums of Chinese typewriting, or modern East Asian information technology, each of these donors had to search far and wide to find a home for these machines.

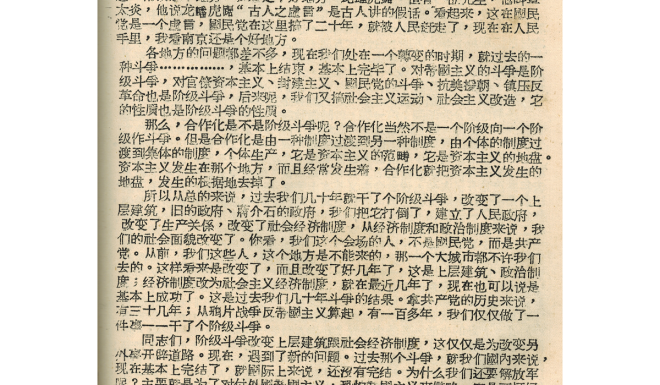

Pick a side: Simplified or Traditional Chinese characters? My heart still sides with Traditional Chinese characters. In part, this is because I’ve become emotionally invested in them after hours and hours of study. My preference is also because of their inherent aesthetic beauty. My exposure to simplified characters was a “baptism by fire.” I still remember, as a junior in college, first arriving in Beijing for my study-abroad year, and being plunged into a world of simplified characters that I had never studied before. As I meandered through the Beijing streets during my free time, looking at street signs and advertisements, I kept trying to match the simplified characters I saw with the traditional ones in my memory. I still remember vividly the day that I first recognized “电” as the simplified version of “電” (“electricity”). I felt like I had cracked the Mayan Code or something, and let out a big “Ohhhhhhh” of epiphany! Silly, I know, but it’s just one of the many joys of all language-learning, and learning Chinese in particular.