Playing for little brother

As Sputnik 1 blasted into orbit, Soviet violinist David Oistrakh stepped off a plane in Beijing. His now reissued music would have a lasting impact in China, finds Oliver Chou

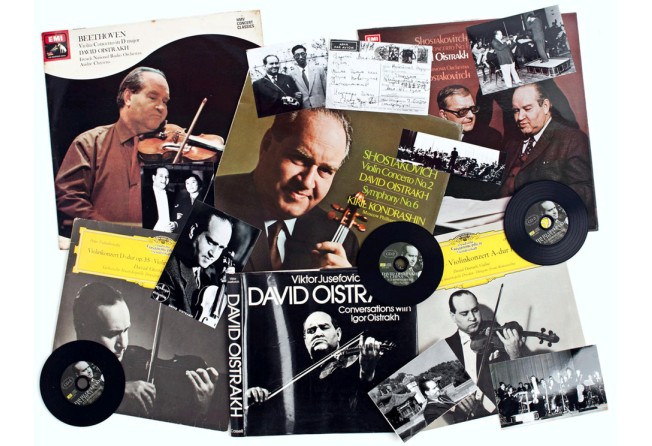

Clockwise from top: David Oistrakh with Mao Yukuan; a postcard from Oistrakh to Mao; rehearsing with Li Delun and the Central Philharmonic Orchestra (CPO); playing with the CPO; Oistrakh at the Winter Palace. All photos courtesy of Li Delun and Mao Yukuan

A missing page from the workbook of one of the greatest violinists of all time has come to light after gathering dust in a Chinese archive for more than half a century.

David Oistrakh was a hugely sought-after classical music legend during his lifetime, and even after his untimely death in 1974, recordings of the Soviet violinist, along with memorabilia devoted to him, have been collected eagerly.

"His technical mastery was complete, his tone warm and powerful, and his approach a perfect fusion of virtuosity and musicianship," is how The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians sums Oistrakh up.

With the Cold War as a backdrop, each of Oistrakh's performances outside the Soviet Union was a sensation. After having toured France and Britain, he made his debut in the United States in 1955, introducing Shostakovich's Violin Concerto No1, which was written for and dedicated to Oistrakh. At a time when Senator Joseph McCarthy was looking for Reds under every American's bed, the usually ideologically hostile US media praised the Odessa-born violinist's elegant, classical temperament. Fritz Kreisler, then 80 and himself regarded as one of the greatest violinists of all time, rose to his feet to hail Oistrakh during thunderous applause at Carnegie Hall.

While Oistrakh's tours to the West, including Japan, have been well documented, his visit to China in 1957 has been all but forgotten, as had the live recordings the nascent China Records made of his performances in Beijing and Shanghai. The trip goes unmentioned by The New Grove Dictionary, and even on the official website of Oistrakh's charity foundation,

Last month, the state record company's Shanghai branch re-issued Oistrakh's China takes, in a four-CD boxset, which die-hard fans had been awaiting for decades. There are very few copies of the original eight vinyl-record set in existence, thanks to the Sino-Soviet rift in the 60s followed by the decade-long Cultural Revolution, periods during which the records were destroyed; in less than ten years, the slogan "Learn from the Soviet big brother" of the 50s had been amended to "Down with the Soviet revisionist."

The set, titled David Oistrakh in China, not only restores three hours and 42 minutes of the master's silken sound, but also revisits a time when musical and political ties between the communist neighbours reached a crescendo.

The goings-on in Beijing in 1957 might have escaped the most meticulous of present-day chroniclers, but they have not been forgotten by those who were there with the maestro.

"His arrival was like a thunderbolt to us," says Mao Yukuan, Oistrakh's interpreter, who now lives in Tuen Mun, Hong Kong. "There had been Oistrakh fever since his recordings on vinyl arrived at the Central Conservatory of Music in 1950. We teenage students used to revere other great violinists, such as Fritz Kreisler and Jascha Heifetz. But Oistrakh opened us to a new sound.

"There was a violin professor visiting from East Germany, and he held a lecture on comparing Heifetz and Oistrakh, and their recordings of the Beethoven concerto were played. Most of us voted for Oistrakh's as the better version," Mao says.

Mao, now 81, has suffered from glaucoma and can now hardly see a thing, but his memory of the late Soviet master remains crystal clear.

"I was 25 at the time, exactly the same age as his son, Igor, a great violinist in his own right. I was then with the Central Conservatory's translation section, and was assigned to be Oistrakh's interpreter throughout the entire tour [of 19 days], plus write his profile in all the house programmes. So from day one, at the airport, every morning at breakfast time to bed time and, the biggest privilege of all, at all his practice sessions, I was with him.

"I came to know the secret of his great musicianship, which came from his great personality," Mao says.

On October 4, 1957, the day Oistrakh arrived in Beijing, the Soviet Union launched the satellite Sputnik 1, signalling the beginning of the space race. The euphoria in the socialist camp, including China, was not shared by Oistrakh, however, who had landed in the pouring rain at Beijing airport with his piano accompanist, Vladimir Yampolsky.

"The plane they were on was a Tupolev-104. After Beijing, it crashed on its way back. The news got Oistrakh rather upset," Mao recalls.

The master recovered well enough to carry out his official duties, part of cultural festivities to celebrate the 40th anniversary of Russia's October Revolution, and would play Mozart and Beethoven concertos, each with a different orchestra, in Beijing, a Tchaikovsky concerto with the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra and two programmes with Yampolsky.

Also in Beijing was Oistrakh's compatriot Sviatoslav Richter, a well-known pianist, and his mezzo-soprano wife, Nina Dorliak. Richter's China tour took place three years before he first visited the US. In 1960, America welcomed him with great fanfare.

With two top Soviet musicians performing in the Chinese capital, the October National Day of 1957 marked the zenith of Sino-Soviet relations.

"We called them big brother, so it's just natural that we as young musicians learned from them in classical music," says Fan Shengkuan, then a leading violinist of the Central Philharmonic Orchestra in Beijing, now 80 and still living in the capital. "But when we learned that it was Oistrakh who was coming to perform with us, we were absolutely blown away.

"We were then a very young orchestra, and our performing level was less than that of a student band. But Oistrakh was very patient with us, coaching us during rehearsals like a master-class. He would play a passage and ask us to do the same. His advice was always cordial and never condescending. He was a great man," Fan says.

"Despite his genius, he practised very hard, up to the last minute before the performance. We could hear him in the hallway, and were impressed with his striving for excellence. The way he played was absolute beauty, with flawless intonation and pure clarity. No one I have heard has come close to Oistrakh, not even [Itzhak] Perlman, [Isaac] Stern or [Yehudi] Menuhin," Fan says.

Zhu Xinren, who was in the second violin section at the time and was later the orchestra's party secretary, says there are no words to describe the excitement he felt to be playing with Oistrakh.

"He was the first world-class musician we had ever performed with, and it was also the first time we heard the sound of the Stradivarius violin. He brought with him not one but two," says Zhu, who is also 80 and still living in Beijing. "He loved his Strad, and would clean it with a cloth thoroughly after each rehearsal. We all surrounded him and watched him wipe the wood spotless, over and over again. Can you imagine, a master doing the cleaning all by himself right in front of us!"

Fan and Zhu are delighted at the China Records rerelease, which contains the Mozart's Fifth Violin Concerto they performed with Oistrakh. Neither had heard the recording before.

"We were then very young, and had not gone through the Cultural Revolution. When Isaac Stern played with us in 1979, we were still healing from the wound of the decade-long ordeal. So the Oistrakh recording will certainly bring back a lot of memories," Zhu says.

Mao got to know the more personal side of Oistrakh. "He shared with me a lot of jokes during our travels, which took us from Beijing to Tianjin and Shanghai, and back to Beijing. Once I greeted him at his room in Qianmen Hotel in Beijing and noticed he looked tired. 'I was invaded by Genghis Khan last night,' he told me. What happened was, a Mongolian performing troupe was also staying at Qianmen, and its conductor, an enthusiastic chess player, knew Oistrakh, a master in chess, was in the hotel, and they played to the early hours.

"On another occasion, I found him listening to jazz music on Voice of America, and that shocked me to the guts, as my Soviet big brother was enjoying what we referred to as 'decadent and poisonous bourgeois music' on an enemy station. So I asked him why he listened to jazz, and he answered, with a smile, 'It's no big deal.' That reply from my role model hit me like a rod," Mao says.

Aside from the usual tourist sites such as the Winter Palace and the Heavenly Temple, Mao took Oistrakh to a traditional medicine session, knowing the master's heart condition (Oistrakh died of a heart attack during a concert tour in Amsterdam in 1974).

"He wrote in a letter later that the prescribed herbal medicine didn't seem to work on him. The letter, handwritten and stamped by Oistrakh personally, was one of a few he sent me after he left. He even sent me a New Year's postcard, which he said he would, and he kept his promise despite a super-busy schedule.

"It never stops amazing me that a world-class maestro would bother to hand-write a four-page letter, plus send an autographed photograph, to a small potato like me," Mao says.

Mao certainly remained a small potato in the eyes of his own government. Less than a week after the Sputnik launch, Oistrakh performed for a private audience at the Soviet embassy. It was an unprecedented event in the history of the Chinese Communist Party; the entire Politburo, led by its chairman, Mao Zedong, congregated for a recital by a world-class violinist.

Mao Zedong was there but Mao Yukuan was not. "Oistrakh was very displeased that I was left out at the embassy recital, although there was nothing he could do about it. It was just the reality in China."

As for the performance, "After finishing his long programme, Oistrakh played a Chinese encore, Rondo, by Ma Sicong [the director of the Central Conservatory], which he never performed before or after," says Dr Victor Yuzefovich, a US-based musicologist who knew Oistrakh and whose son, Igor Yuzefovich, is the incumbent concertmaster of the Hong Kong Philharmonic.

"Oistrakh was at his peak then, musically," says Yuzefovich, the author of David Oistrakh - Conversations with Igor Oistrakh. "Just two years earlier, in 1955, he had premiered Shostakovich's First Violin Concerto in Leningrad and had a brilliant debut in America. His then and subsequent tours in America would always serve as breakthroughs in the relations between the two countries, greatly complicated by the Cold War."

The exclusion Mao Yukuan suffered at the Soviet embassy was not a one-off. Oistrakh performed five times, including at the embassy, in Beijing in 1957. "There was one concert when Marshal Chen Yi [the then mayor of Shanghai] came," Mao says. "Afterwards he went backstage to greet Oistrakh. His bodyguards pushed me out as if I were an assassin. The master was not happy. So when [chairman of the State Planning Commission] Li Fuchun, another big shot, came after another concert, Oistrakh held on to my hand so that we couldn't be separated, and the greetings ensued," Mao says.

Mao remembers Li, then a vice-premier, expressed his appreciation for Oistrakh's encore piece, Debussy's Claire de Lune.

"It was unusual to hear Debussy's music in China at that time because the French impressionist school was the official demarcation line that was drawn between classical and modern music. The latter, of course, meant decadence, according to official standards at the time."

A major work in the programme that has never been released, even in the original set, was Cesar Franck's Violin Sonata in A Major. But Yang Baozhi, who as a fresh violin graduate sat in the front row at the Oistrakh recital at the Central Conservatory, remembers listening to it as though it was played yesterday.

"Without a title or theme, the Franck sonata was not a welcome piece according to the official socialist realism then. No teacher would teach it, and the score I had was bought in Hong Kong," recalls Yang, who now teaches and composes from his Sha Tin home.

Unfamiliarity, led to embarrassment at this performance. After the stormy ending of the second of four movements, the audience clapped and two young students, thinking the piece was over, proceeded to the stage to present flowers to the maestro.

"Oistrakh was furious," says Yang, "and stared at those two poor girls, signaling them not to go any further with a stern face. The incident shows the somewhat low level of music appreciation that existed then, even among conservatory students."

Not that Yang was lacking in appreciation: "It was like God playing in front of us. You had to be there to believe.

"His music became my inner peace for the next 20 years," says Yang, who had been branded a "rightist" during the national political campaign of the summer of 1957. He would spend the next two decades in Sichuan province, working as a logistics technician at a song and dance troupe.

Ironically, Yang had received his public criticism in the same hall in which he saw Oistrakh's recital.

"His music transported me to another world, a bliss," Yang says.

Compared with the treatment meted out to conductor Li Guoquan, two decades of exile seems tolerable. As Li led the Central Experimental Opera Orchestra in accompanying Oistrakh in the Beethoven concerto, he could not have imagined what the future had in store for him.

"With Oistrakh's diligence and humility, our respect and affection for him will go on for a long time," Li wrote in the official Beijing Daily newspaper, two days after the Beethoven performance.

It was not to be, however. Before long, Sino-Soviet relations took a nosedive. In 1960, Moscow pulled out all its experts from China. The schism was sealed.

"I lost contact with Oistrakh after his last letter to me, dated October 16 1958," Mao says. "In the autumn of 1960, along with a few thousand individuals from other parts of China who had previously had any contact with Soviet experts, I was summoned to the Friendship Hotel, which was formerly lived in by the Russians.

"There we went through a thorough rectification to self-criticise and expose wrong-doing. We also listened to reports by senior leaders such as Marshal Chen Yi on the latest situation and Soviet revisionism. The exercise was so secretive that even family members were not to be told.

"The whole thing lasted a few months," Mao says. "We all faced the same problem: it had been our job to receive the Russians, an honourable one at that. So there had been no specific guidelines as to what to do and what not to do during the reception. It only became a problem afterwards, due to reasons no one could have foreseen," he says.

For the two conductors who performed with Oistrakh, Li Delun (in the Mozart concerto) and Li Guoquan, however, there was worse to come than closed-door meetings at a hotel to examine their "faults".

Both men suffered from the excesses wreaked by the Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution. Li Delun, a Moscow Conservatory graduate, would become a bicycle technician. Li Guoquan decided to end his life, having had enough of being beaten up and humiliated (including having his head shaved). On August 26, 1966, aged 52, he killed himself near his Beijing home.

For the first time in many years, Li Guoquan and Oistrakh can again be heard performing together. The recording also features Li Jue, the widow of Li Delun, who led the second violin section of the opera orchestra in the Beethoven recording.

"These recordings have an epochal significance," Mao says. "For the first time in China's long history, a world-class master was performing not one or two commercial concerts, but truly sharing his distinguished art with all walks of life, from state leaders to conservatory students. Oistrakh loved Chinese culture and, along with his pianist Yampolsky, filmed most of the sightseeing with their hand-held recorder. It's a pity we did not take it seriously enough to document all the things Oistrakh did and said during his China tour. What I can now remember is just a tiny bit of it."

For Dr Yuzefovich, the resurfacing of recordings long considered lost is an indispensible addition to the legacy of his compatriot.

"I think the release of this set of recordings has a great deal of significance. Mainly because every new release of this great musician is a historical document. But its importance in this case is due to its rarity, in particular - it deals with Oistrakh's one and only tour in China."