As happy as Larry

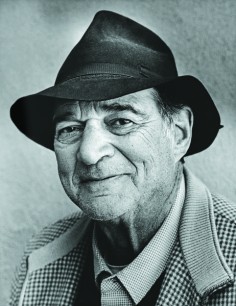

The American artist behind the 'Light and Red' exhibition now showing in Central speaks to Fionnuala McHugh about rage, age and hallucinations.

Larry Bell - painter, sculptor, long-distance driver, dog lover and 1960s icon - was in Hong Kong recently. Usually he divides his time between his studios in Venice, California, and Taos, in New Mexico, but he'd come here for the opening of his exhibition titled "Light and Red". His work is being shown at White Cube, which seems appropriate because if there's any shape with which Bell is associated, it's a cube.

For years, he created boxes out of glass. If you look at them now, you eventually reach a point where you can't quite decide if he's trying to express the beauty of containment or if he's signalling a desperate urge to escape. In 2011, as part of the 54th Venice Biennale, six of his 1960s cubes were set on six pedestals in one of the gilded rooms of the Palazzo Contarini Degli Scrigni. The photographs of the installation capture a wonderfully translucent zoo of caged light.

That exhibition was titled "Venice in Venice: Glow & Reflection - Venice California Art from 1960 to the Present", and showed the work of a group of young, experimental Californian artists who hung out together in Los Angeles under a sky so perfect it had, 50 years earlier, attracted what used to be called the moving-picture industry.

And the bronze stick-man outside Langham Place, in Mong Kok, which weighs an un-spindly 2,700kg, that's by Bell. It's No26 in a group of 27 works from his "Sumer" series.

The figures grew out of some electronic doodling on his Mac in 1993, which he initially sent to long-time friend, architect Frank Gehry, who wanted ideas for a client's house. The series takes its name from the Sumerians, who lived about 7,000 years ago in Mesopotamia, the cradle of human civilisation, and it has been interpreted as a commentary on "the post-human condition". There may be those who wonder if this cultural reference in Mong Kok on a busy Saturday afternoon is, rather like the glass boxes, sending out a mixed message.

At any rate, it was the architect of Langham Place who called the figure Happy Man. Bell's namecard has a whole row of them stick-dancing, stick-bending, stick-arms-akimbo.

IN A BACKROOM IN White Cube, in Central, early on the evening of the Mid-Autumn Festival, as the city prepares itself to focus on (moon) light, Bell - rather heavier than he was when a pal, the actor Dennis Hopper, took photos of him nattily dressed in striped trousers and corresponding shoes half a century ago - is craggily handsome in a red gingham shirt.

He's now 74. Is he a Happy Man?

"I can't tell sh** without these," he says, holding out the two hearing-aids, like a pair of pink broad beans, he's just removed from his ears to be admired. "Sometimes they work, sometimes they get plugged up with wax."

Bell bears an ironic name. When he was 46, he was told by a consultant that he'd had profound hearing loss his entire life. He'd only made the appointment because someone in Los Angeles, who collected his work, had slammed her cutlery on the table at a smart dinner-party and shouted, in frustration, "Larry, get your damn ears checked!"

The doctor professed additional amazement that he didn't stutter.

"When he said that, it was like an electric shock going through me," Bell recalls. "Because when I was growing up, I couldn't get a sentence out."

How could he possibly go through more than four decades without someone noticing?

He shrugs. "I asked my mother that, before she passed. She said she didn't know. My parents … the teachers … maybe they thought I was retarded. In those days, they didn't have those sort of tests at school."

Once diagnosed, he was fitted with hearing aids. "At first I thought I was Superman. I could hear the birds in the trees, I could hear the tyres on the streets - that hissing sound you don't hear anymore. All kinds of things.

"And then I had a strange experience when I started having these … hallucinations, memories I had of myself as a child, usually being punished by my parents for things I was told not to do that I didn't know not to do, or doing poorly at school. I'd have these black rages while I was driving and I'd find myself 50 miles past where I was supposed to be, holding the wheel, white-knuckled. I thought I was going crazy."

Professionally, he says, with an unconscious echo of the consultant, that time had "a profound effect". He went back to the doctor, who told him that such anger "was not uncommon". He wouldn't do another series of cubes for eight years. Listening to his recollections of that rage, you realise how boxed-in he must have been. All those transparent walls …

Which doesn't mean he was a hermit. One of the reasons he eventually moved to Taos was to remove himself from the myriad diversions, not all of them healthy (or legal), that 60s and 70s Los Angeles offered.

A brief insight into his social life, and into musical standards of the era, is that he, Gehry and the artist Ed Ruscha once formed a band in which Bell played the guitar, Ruscha a kazoo and Gehry a bell (from a bicycle).

"I didn't feel isolated from the studio activities of working artists," he explains later. "I've never had a problem communicating about that."

But the work needed to speak loudest of all. His original ambition was to be an animator. He'd been born in Chicago but his father, who sold insurance, moved the family to California when he was six. He drew cartoons at school and then went to Chouinard Art Institute, considered so predictable a path to Walt Disney Studios it was known as "the mouse house". (Chuck "Looney Tunes" Jones was also a former student.)

Unfortunately, Bell failed to fulfil class assignments and sat drawing squares and rectangles. Soon, the only frames he was working with per second were in the framing shop where he got a job.

He rented a studio a block away from the ocean in Venice and painted. His output began to morph. At first, he incorporated mirrored surfaces in his two-dimensional creations. Then he made little "constructions" with bits of leftover glass and wooden boxes, playing around with reflection and dimension. He started to coat the insides of the glass with a thin, metallic film. It was part of the zeitgeist, in that community of beach-boy artists who loved their cars, to be fascinated by surface polish; so many of them were applying auto enamels, lacquers, resin and acrylics to their work that, in the end, they would be known collectively as the Finish Fetish movement. (It may have been a time of breaking down barriers but human nature likes its labels.)

The Vietnam war was in the process of being lost; he was drafted but managed to get himself rejected by the board. The army medics seem to have missed his hearing problem, too. Suzanne Herskovic Ponder, Bell's partner for the past few years, who's cheerfully sitting in on the interview, says, "He's got a funny story about that" but Bell simply says, "I'm unfit for employment of any kind - if I went into the army, everyone should sell their defence bonds."

In 1962, he had his first show at Los Angeles' influential Ferus Gallery. Shortly afterwards, three men in suits knocked on his door. Bell - in a response which may be familiar to some of Hong Kong's creative residents - was convinced they were building inspectors and, as he wasn't supposed to be living in his studio, hid. Eventually, after peering through a crack in the window, he invited the trio in, misheard the introductions, and only when the visit was well-established did he realise he was hosting artist Marcel Duchamp.

First of all, what was he wearing? "Oh, I was pretty well turned-out," Bell says, comfortably. "Duchamp was a pretty slick guy himself, a very conservative dresser. Formal. He was sitting in his parlour, smoking a cigar. He did it very eloquently. Very elegantly. He smoked it like this."

Bell borrows a pen, places it between the little finger and ring finger of his left hand, makes puffing gestures.

"I was 25, he was 73, 74. [Actually, Duchamp was 78.] It wasn't a big room, about the size of this one" - a glance around White Cube's back office - "but there was a Brancusi, a de Chirico, a Magritte. I couldn't take my eyes off the Brancusi and he paid no attention to it. I thought, 'I'm in a room with a guy who thinks being with a Brancusi is nothing.' Brancusi was my great hero, everything he did was so simple."

Teeny, Duchamp's second wife (who was American and had been married to Matisse's son, Pierre), brought in some food. The dazzled Bell, on the launching pad of his career, sat while Duchamp - who would die three years later - talked about a show he was planning of his early work. "I said, 'Really, how early?' And he said, 'Oh, I was four or six.'"

Now the slim-hipped, fashion-plate dude he was is almost as old as Duchamp on that afternoon in 1965. As if reading my mind, Bell says, unprompted, "I'm not jealous of my age then. I like myself more now than I did when I was younger." Why? He pauses. "I'm celebrating my 54th year of employment. I've managed to do my thing all of this time. I don't feel any value in my trip other than working … I'm nothing but what I do."

The reason he was in New York that year was to exhibit his work at Pace gallery. The show was a success: a West Coast statement of artistic arrival intended to be heard along the East Coast. At the time, Bell was paying to have his glass-coating process done in Los Angeles by a company he'd found in the phone book, but someone suggested that he start doing it himself; so he bought the necessary equipment second-hand in New York (it was huge enough to be nicknamed The Tank), plus an instruction manual titled Vacuum Deposition of Thin Films, and based himself in the city for the next few years.

In an interview in Hunter Drohojowska-Philp's book Rebels in Paradise: The Los Angeles Art Scene and the 1960s, Bell is quoted as saying, "I made more money when I was 25 than my dad made in his whole life. I was totally unprepared … It gave me a nervous breakdown by the time I was 30 and turned me into an alcoholic."

"There were hard times financially," he admits now.

He was married (he'd met his wife, Gloria, at a Duchamp opening at the Pasadena Art Museum) but the money was flowing through his fingers and he was adrift. Success made him feel simultaneously guilty about those artists left behind in Los Angeles and baffled by those artists he met in New York. He returned to California and then, in 1972, to New Mexico. In deliberately-enforced isolation, the work - the muse, he calls it - kept him going.

His son, Oliver, is a videographer, and nowadays, of course, the whole world can watch short films of his studio on Vimeo. "I don't believe in intellect," Bell says firmly. "It has to be hands-on."

In the clips, Bell and his assistants (he has five) move around wearing white face-masks: the vacuum process requires that the glass be spotlessly clean. There's an iconic note to that, too. Hopper told him that the masked look he wore, to devastating effect, in his role as Frank Booth in the film Blue Velvet was partly inspired by Bell.

Time for Bell's close-up.

"Squish your hair, Larry," says Herskovic Ponder before he goes off to be photographed, adding, fondly, "These artists are such hippies." (Bell's sign-off to his emails is, indeed, Peace and Love.) Decades ago, Bell had been a customer at her parents' photography store in Los Angeles, which had a stellar clientele; other customers bringing in their snaps for printing, in those pre-digital, pre-selfie days, had included Elvis Presley, Marlon Brando and Tony Curtis.

They met again several years ago, by which time Bell was divorced, had re-rented his former studio in Venice - "After 30 years, I needed a scene where there was some action", he says - and was commuting there from Taos.

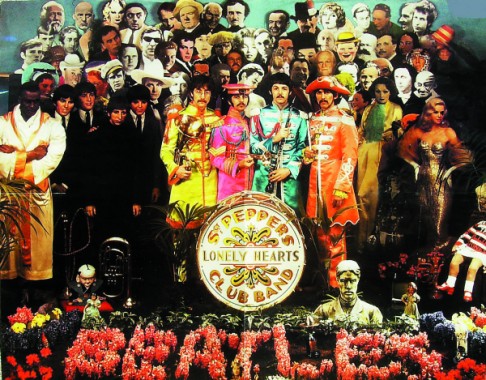

This is his third show with White Cube. At the London opening, last October, Sir Peter Blake - the British artist who co-designed the "Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band" cover with his now-ex-wife - came to say hello, and to show him photographs of how the image was created. In an early montage, Adolf Hitler (one of John Lennon's choices) was standing to the right of Bell until wiser counsels prevailed. In the end, Bell was placed between Tyrone Power, the actor, and David Livingstone, the missionary explorer to whom Henry Stanley addressed his famously presumptive remark.

On the gallery's walls are a series of scarlet-bordered collages he created on paper he had made in Japan. The red is the loudest red he could find. He was, he says, playing with the idea of strength. He points out the design of the glass boxes: they're a little deeper at the top than the bottom to make them less reflective so what you see isn't just surface light but the texture within. Downstairs, his "Light Knot" sculptures, made from polyester film, float calmly in space, as if they carry no weight at all. Those glass boxes have been specially designed, too; they're wider at the top than the bottom, "to change the feeling of the container". It is, he says contentedly, "a very good show".

He always does the 1,000-mile journey between his Venice and Taos studios by car; he's clocked up 400,000 miles in his Chevrolet Suburban. Until a month ago, when the coughing got too bad, Bell - like Duchamp - was a cigar-smoker and the only constant companion who would tolerate the auto-fug was Pinky, his bulldog. That's when he does his meditating, when Pinky and he are on a road trip. He switches off the radio, takes out his hearing-aids and drives with his thoughts through the happy, silent night.

Larry Bell's "Light and Red" exhibition will run at White Cube, 50 Connaught Road, Central, tel: 2592 2000, until November 15.