Chinese collectors' passion for Picasso skews global art market

Pablo Picasso has become the Louis Vuitton of the Chinese art world, as collectors pay sky rocketing sums for the 20th-century icon's louder, later works, writes Patrick Lecomte

If the art market is any indication of tastes, the millions of dollars spent by Chinese collectors on Pablo Picasso's paintings stand as a beacon that marks the love affair China is having with the 20th-century Spanish painter.

At a Christie's auction in New York in 2013, Dalian Wanda Group, a real estate and entertainment conglomerate, bought a Picasso painting from 1950 titled Claude et Paloma for US$28.2 million. It had been estimated the work would sell for between US$9 million and US$12 million. Following the sale, Guo Qiangxiang, who is in charge of the company's art collection, told the media: "This painting is Picasso's masterpiece, completed in his prime, so to pay US$28.2 million for the artwork … I think that it's decently priced, and I'm very satisfied with it."

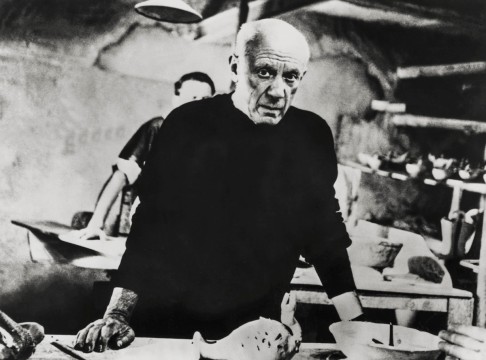

The purchase is one of many examples of the growing interest of increasingly sophisticated Chinese art lovers in the artist, who died in 1973, aged 91. So, what is it about Picasso that gets the Chinese excited?

The first Picasso artwork to publicly reach the mainland's shores was of a bird - a pigeon, often portrayed as a dove, that graced postage stamps issued by the People's Republic of China in August 1950. Two years later, a couple of Picasso's doves were exhibited behind the praesidium of the Asian and Pacific Peace Conference, held in Beijing. By then, through personal friendships - French communist writer Louis Aragon used one of Picasso's pigeons to illustrate the World Congress of Advocates of Peace in Paris, in 1949 - and international politics - because the artist identified himself as a communist his work was embraced by red leaders - the artist's birds had become a highly popular part of cold war iconography. They would become familiar motifs at National Day parades in Tiananmen Square.

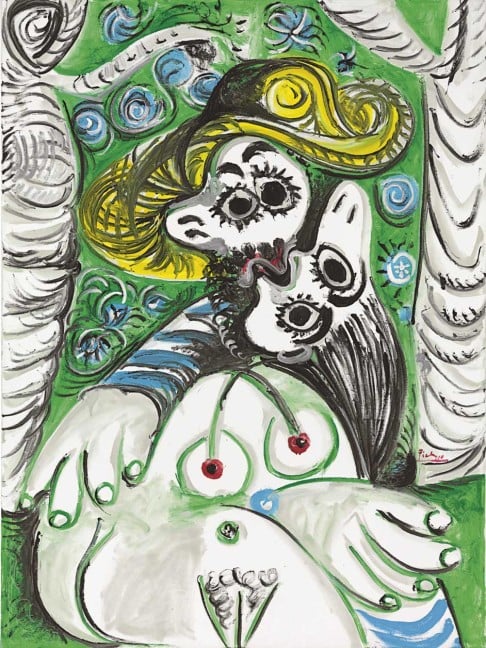

However, Picasso wasn't to truly "arrive" in China until 1996, when, following the initiation of Deng Xiaoping's open-door policy, two German collectors and art patrons, Peter Ludwig and his wife, Irene, donated 89 paintings worth US$27 million to the China National Museum of Fine Arts, in Beijing. The donation included three paintings and one ink drawing by Picasso, notably works from the painter's last period (1960s-70s), which was characterised by large-format and colourful paintings of quirky musketeers and naked female figures.

In 2003, in an act of art diplomacy, then French president Jacques Chirac opened a Beijing exhibition of 25 Picasso paintings the French state had received from the painter's heirs in payment of estate duties two decades earlier. Since then, numerous exhibitions have showcased Picasso's artwork in China, including a three-month exhibition, in 2011, of 48 paintings, prints and sculptures from Paris' Musée Picasso at the China pavilion at the former site of the Shanghai World Expo.

Over the past 12 months, Picasso's art has attracted crowds all over the country: masterpiece etchings from the 1930s Vollard Suite collection in Beijing; ceramics in Zibo, Shandong province; paintings in Nanjing and Wuhan. Even the online community has joined the fray: a Picasso print dated 1963 was offered on Taobao in May. No other Western artist has had such exposure.

Picasso's pedigree seems to fit perfectly with modern Chinese history. Although a strong supporter of communism, Picasso never avoided the market and, along with his dealers, became extremely wealthy by selling his works from early in his career. His life was anything but the 19th-century cliché of a starving artist struggling to make ends meet. Because of that, narratives about Picasso during his lifetime, or what sociologists call the "process of mythologisation", revolved around his creativity and wealth - somebody is as rich as Rockefeller; a painting is as valuable as a Picasso.

The association of Picasso with wealth seems to have gone a long way in Chinese popular culture. For instance, in a blockbuster mainland television series aired last year titled Scarlet Heart 2 ( Bubu Jingxin), one could not help noticing a Picasso painting, most probably from the 1940s, exhibited like a trophy over the uber-rich tycoon's mantlepiece in an otherwise totally Chinese luxurious interior. So has Picasso become to art what Louis Vuitton is to luxury goods; a status symbol associated with the rich and famous but aimed at the masses? In this case, it is probably more than label snobbery.

Discovering new forms of art can be disconcerting. Picasso's signature, akin to a brand, reassures Chinese who may be confronting foreign art for the first time that they are dealing with the quintessence of 20th-century Western creativity. After all, as Christie's put it in a catalogue aimed at Chinese collectors, "Picasso was the father of modern art in Europe and his influence remains strong throughout the world."

For market players, China's newly acquired taste for Picasso is a boon. The artist's unrelenting creativity led him to produce thousands of works during his lifetime - an estimated 50,000 over 75 years - and create a variety of artwork that is now accessible to a wide range of collectors, from paintings sought after by the very rich to non-signed, printed works worth a few hundred dollars. Demand from China is likely to make them all worth more.

International auction houses eager to expand in the mainland are not immune from this craze. Every art auction organised by Christie's in Shanghai over the past two years has offered a Picasso painting for sale. To promote Picasso to their rich mainland clients, auction houses organise private events and exhibitions that often draw on far-fetched "correspondences", or cultural connections, to position Picasso's works within reference frameworks familiar to their target market (such as the wu xing, or the five elements, common in Chinese culture). As mentioned by one Chinese participant in Christie's first mainland auction, Shanghai in 2013, "I am not interested in all Western works, only in those which strongly influenced Chinese art."

Using Chinese references may well be a cultural fudge, but it seems effective. Notably, in September 2013, two months before the New York auction, Christie's exhibited in Shanghai works from the Jan Krugier Collection, of which the painting bought by Dalian Wanda Group was originally part.

Curiously, the Picasso paintings wealthy Chinese seem to prefer tend to be from the artist's last creative era (1960s onwards), which has been consistently judged by Western collectors and art experts as being less desirable than periods such as that which encompassed cubism, an early-20th century avant-garde movement pioneered by the Spaniard. Large and loud, these later paintings make a bold statement on any wall.

As a result of Chinese demand, some late Picasso paintings have recorded astoundingly high returns in recent years as shrewd Western collectors and art dealers cash in by selling their art. For example, in 2010, Christie's London sold for US$18 million a 1969, brashly painted, sexually explicit canvas called Le baiser, ("The kiss"), which had been purchased for US$4.2 million by an American businessman in 2003.

Taste is a matter of personal preference and cannot be judged. However, Chinese buyers are inflating prices and effecting the selection of works for sale in the global market. And there is a risk in that.

In terms of investment value, there may be better ways for Chinese collectors to diversify their wealth than by paying record prices for Picasso paintings that appeal mostly to other Chinese buyers. Why not consider a blue period painting of the early 1900s instead? That could prove a better investment in the long run.

The beauty of Picasso is that there is no shortage of styles to choose from. Alternatively, there are Matisse, Kandinsky and many other pillars of modern Western art to consider.