Why Hong Kong has the Fujianese to thank for sweetcorn

Sweetcorn’s roots stretch back to Central America, writes Jason Wordie

Now in season at wet markets, sweetcorn has recently become a more popular – and thus widely available – vegetable. Small holdings in the New Territories increasingly farm it; sweetcorn’s vertical growth ensures a good return for the amount of ground the crop needs – even more so with modern heavy-yield hybrid varieties.

But the local product only accounts for a small amount of the sweetcorn consumed here; as with most other vegetables, much of Hong Kong’s market supplies come from the mainland.

Sweetcorn and maize were introduced to China from Central America, via the Spanish colony of the Philippines and the Portuguese outpost of Macau.

From there, they spread to the rest of maritime Asia. Other “new world” foods were also pioneered; probably the most important such crop being the yam. Yams grow well in poor soil and their roots and leaves helped quell hunger, famine and consequent social unrest. Tomatoes were also introduced, as were guavas, papayas and aubergines.

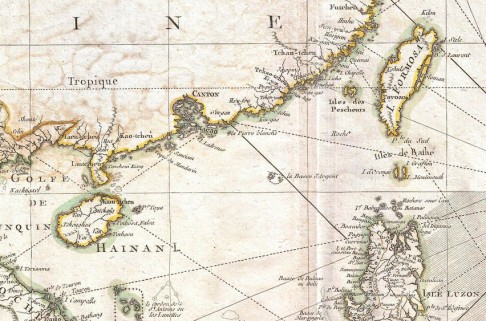

The Fujian ports of Amoy (Xiamen) and Foochow (Fuzhou) had close trading links with Luzon, the largest island in the Philippines, as did Formosa (Taiwan). Little-remembered today (mainly for political reasons), Spanish links to Taiwan pre-date any significant ethnic Chinese colonisation of that island.

Manila, in particular, had close ties with Amoy and Foochow, and many Chinese families had extended branches in both locations, and still do. Chinese migrants often intermarried locally and today’s sizeable Filipino-mestizo community (which comprises much of the Philippines’ political and economic elite) has a substantial Chinese heritage.

Chinese men in Southeast Asia usually sent their sons from local wives to China for education and Sinicisation, if they could afford to do so. Daughters stayed behind and were married off.

Geographical proximity with the Philippines made Amoy a popular destination for this. Many people there today have distinctly Southeast Asian features; gentle questioning often swiftly reveals such heritage.

In the wake of Indonesia’s independence, in 1945, many Indonesian-Chinese with Fujianese ancestry migrated to mainland China. After failing to settle in their culturally foreign ancestral homeland, and with no possibility of a permanent return to Indonesia, they moved to Hong Kong from the 1960s.

North Point developed a sizeable community of these people and became known as Fukien Jai – “Little Fujian”. Tsuen Wan and Tsing Yi also have significant populations of these arrivals. In recent years, more Fujians have settled in Hong Kong, making this group the second-largest sub-ethnic contingent among mainland migrants.

A deliberate dilution of Hong Kong/Cantonese identity can be discerned in this emigration, with shades of the wholesale Han Chinese settlement patterns in troubled/troublesome Xinjiang and Tibet, where the original inhabitants are now outnumbered ethnically, culturally and linguistically by migrants.

An enhanced availability of sweetcorn is one side-benefit of this further wave of mainlandisation, and the resident Fujianese population provide a ready market. A delicious sweetcorn drink can be made from the vegetable: kernels are taken off the cob, quickly boiled, and passed through a juicer. This new “local” favourite originated in Fujian.

In Hong Kong, sweetcorn is commonly eaten boiled, steamed on the cob; but in Fujian, it is more commonly roasted over charcoal, as it is in Central America, from where it first came centuries ago.