From the archives: Occupy insiders give their verdict on the 2014 protests

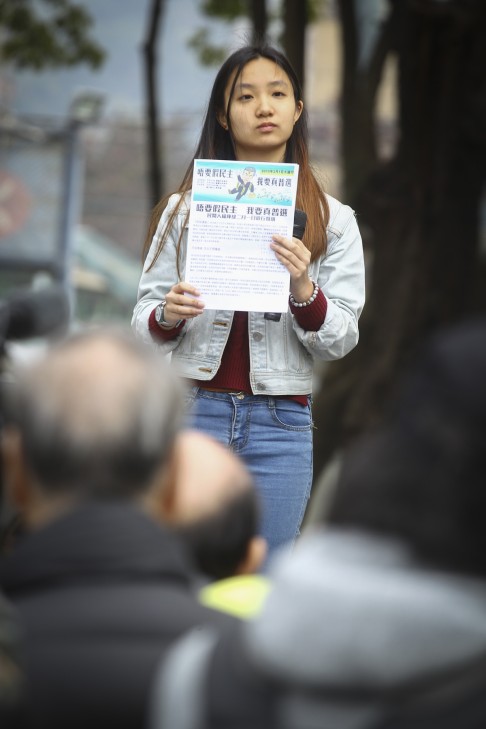

The Occupy movement marked a coming of age for Hong Kong's 'millennials', often referred to as strawberries: self-centred, faint-hearted and easily bruised. In an article originally published in 2015, Mary Hui talks to three women who helped redefine a generation

It was around 10.30pm on a Friday night in Hong Kong. Hundreds of students had gathered outside the government headquarters in Admiralty. That week, starting on Monday, September 22, thousands of students across the city had boycotted their classes to protest against a disappointing political reform proposal put forward by Beijing. Now, the city was waiting to see what would happen next: would the movement fizzle out or would it intensify?

Before the students stood a hastily erected three-metre-high fence; beyond was an open area, dubbed Civic Square by the protesters. This was what they had come to take.

Standing on the front line, Gloria Cheng Yik-lam, 20, saw a small gap in the fence suddenly open. Why is not clear, but Cheng, a member of Scholarism, a youth activist group that had played a leading role in the protests, seized on her chance and pushed forward, forcing the gap open wider, and rushed in. Others followed. Some protesters had already found their way in by scaling the fence.

"I was surrounded by police officers as soon as I entered," says Cheng, a third-year student at Chinese University who had been on protest marches before. Then someone - either a security guard or a policeman - placed a lock hold on her neck. She found it hard to breathe. Behind her, chaos was unfolding as students and the likes of lawmaker "Long Hair" Leung Kwok-hung tried to push their way in and the police used pepper spray to try to keep them out.

Eventually, someone managed to free Cheng, and she bolted. To evade a policewoman, she pretended to faint, crumpling to the ground. Not knowing what to do with her, and perhaps having been called away, the officer left. Cheng got up and ran to the raised circular platform at the centre of the square. There, she sat down and linked arms with about 200 other students as the police looked on.

The students had taken Civic Square.

Evelyn Char Ying-lam, 29, a freelance writer, was having drinks with a friend that evening when she found out Civic Square had been stormed. She rushed to the scene, joining students and others outside Civic Square.

"If [the students] were willing to shoulder such large responsibilities, then we were in no way entitled to shirk away," says Char, when we meet at a fro-yo cafe in Mong Kok, another area that "fell" to the Occupy movement. She considers herself "a typical Hongkonger who is concerned about democracy", having been on many July 1 and June 4 marches.

That night, she and other protesters chanted repeatedly, "Release the students", and, "Students are guiltless". When the police charged to disperse the crowd, they put their hands up, surrounding the officers.

"We tried our best to use our bodies to block them," says Char.

She stayed through the night, watching over the students through the fence.

As the sun rose, Char breathed a sigh of relief: "I thought, finally, the sky is lighting up. We thought, soon, there would be people to take our positions, that we could go home."

The next day, tens of thousands flooded the streets of Hong Kong. For the next 79 days, they would occupy key areas in the largest civil disobedience movement the city has ever seen.

"Without that night, things would not have happened the way they did," says Char. "That was a turning point."

I WAS BORN INHONG KONG and, until 2013, when I left for Princeton University, in the United States, I lived and studied in the city. Over the years, I have heard many a criticism of Hong Kong's students. We have been called by some the "strawberry generation": soft, faint-hearted and easily bruised; stereotyped as quitters, poor communicators and self-centred. In December, I returned to interview some of the young Occupy activists because I wanted to understand the protesters as individuals and how they may be representative of a generation. I wanted to find out how they outplayed the adults, transforming what would have been a small-scale occupation of Central into a citywide "umbrella movement".

From 13,000km away, staring at my laptop screen in my dorm room, I had watched the events unfold at home. It was surreal to see familiar buildings and roads transformed by the crowds that engulfed them. My feelings were a curious mixture of detachment and intimacy, foreignness and familiarity.

My generation has been diagnosed with "Hong Kong kid syndrome", which is known to inflict the "three lows": low emotional intelligence, low resilience and a low level of independence. Employers write guides on how to deal with us. Two labels are also thrown around a lot, often disparagingly: the post-80s - those born in the 1980s - are criticised for having grown up in a greenhouse, being unable to stomach hardships, loving to complain and being irrational, among other things; and the post-90s - those born in the 90s, myself included - are lambasted for lacking a sense of personal responsibility being spoiled by so-called helicopter parents, who perpetually hover around their precious offspring, satisfying their every whim. Post-90s kids have even been known to take their parents to job interviews with them.

Somehow, these same groups had been responsible for starting a civil disobedience movement that captured the world's attention.

"There has always been a tendency to characterise students as immature, as unsophisticated," says Bruce MacFarlane, professor of higher education at the University of Hong Kong. "But, in fact, with what has happened, they have demonstrated the opposite.

"Within this current generation, there is a strong feeling of, if not now, when? If not me, who?"

Pushed on by socioeconomic pressures and a sense of urgency, the students have shown perseverance and courage, and have been unwilling to be discouraged by critics.

ON YOUTUBE, MORE THAN three weeks into the Occupy movement, I watched as student protest leaders and government officials sat down to debate the political future of Hong Kong. It was a stirring sight: five scruffy university students wearing identical black T-shirts emblazoned with the neon-green slogan "Freedom Now" taking on five government officials dressed in suits. The contrast between the two sides was indicative of a broader generational clash that came to a head on the streets of Admiralty, Causeway Bay and Mong Kok.

The officials had been groomed for success under the old Hong Kong system. Chief Secretary Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor grew up in a low-income family, doing homework on a bed because her family couldn't afford a desk. Secretary for Justice Rimsky Yuen Kwok-keung grew up in a public housing estate in Wong Tai Sin, sharing a 200 sq ft flat with his family of eight. For them, the "Hong Kong dream" - the hope that if you worked hard enough, you could make something of yourself - came true.

Now, though, "this group of youths feels that society is sinking," said Alex Chow Yong-kang, secretary general of the Hong Kong Federation of Students, in his opening remarks. "They have been so pushed up against the wall by the government that they have no other option. They must come onto the streets to fight, and only then will their voices be heard by the government."

Ninety minutes later, all the student debaters had heard from the government was "pack up and go home", said Lester Shum, deputy secretary general of the Hong Kong Federation of Students. "The whole generation, awakened by tear gas, cannot accept this. We are the generation chosen by the times. I think the same applies to you - you are the officials chosen by the times. Can you be responsible? Or will you be the ones that kill our political future and be the sinners of a thousand years?" said Shum, in his concluding remarks.

The tension spilled from the streets into homes. Cheng says she avoided bringing up political issues with her family during the Occupy period.

She grew up reading the newspapers regularly and watching the evening news with her family over dinner, she says, but "in secondary school, I wasn't politically involved. At some youth summits, I would talk to peers about current events, but it wasn't about standing out, or really expressing my own opinions. My political involvement was limited to the annual July 1 march, which I went to with my parents."

Then, in June 2012, she joined Scholarism to protest against the introduction of Beijing-endorsed "moral and national education" to the local curriculum. That year, tens of thousands - many of them students - gathered outside government headquarters to demand the withdrawal of the education plan, which, they said, was nothing more than brainwashing and indoctrination, and a threat to the integrity of their education. The plan was ultimately shelved but Cheng still felt that the voices of the people were not being heard.

"Over the years, we've tried marches, protests. When these rather ordinary, routine things ultimately did not work, civil disobedience was the last thing we could do. As Hong Kong citizens, of course, we wanted to do as much as we could," Cheng says.

Cheng spent little time at home during the protests, only occasionally returning late at night to sleep and grab a bite to eat, leaving the next morning.

Other protesters "unfriended" family members on Facebook; a popular video online is of a female protester who purportedly unfriended her mother.

"For your last birthday, I bought you an iPhone so you could learn how to use Facebook. I didn't think I would unfriend you today," she says in the video. "I've also left the family's WhatsApp group." She talks about mounting economic pressures and a society that is "increasingly dark". Reality has changed, she tells her mother.

It is in part this belief - that things are not as they used to be and the opportunities that Hong Kong once offered its enterprising youth no longer exist - that has made the students want to take charge of their future.

Text messaging groups and Facebook feeds have become battlegrounds for warring opinions as those for and against the Occupy movement share articles from op-ed pages and blogs. The adults in my family (I have not unfriended them nor have I left our WhatsApp group) regularly share with me articles that are highly critical of the students. I have often found myself, tucked in bed, late at night, reading these articles on my iPhone and texting back point-by-point rebuttals, making the case for my fellow students who were on the streets.

But the conflict has never been as simple as a mere generational divide.

"Some think it is a clash of generations. Others think it is a clash of values. I think it is both," says Johannie Tong Hiu-yan, 20, who I meet at a Starbucks in Mong Kok.

Tong was among those who stormed Civic Square in September.

Tong first became aware of socioeconomic and democratic issues when, as a first-year student, she joined HKU's Federation of Social Work Students. She left the organisation in a regular rotation of personnel but was involved in organising the class boycott on campus in September. As the week-long boycott neared its end, she and others tried to think of a way to build on the momentum they had established.

"Originally, we were trying to think of some kind of action that would call Hong Kong people out, to tell them that the boycott was not only about students, that it did not revolve only around students," she says, sipping on a green tea latte.

Tong says that after two years of her being politically active at university, her parents were prepared for her involvement in the protests, being "supportive but sometimes worried", especially when certain areas, having been infiltrated by gang members, became dangerous and the crowds mob-like.

WATCHING OVER KOWLOON, Lion Rock is a 1,600-foot outcrop that resembles a big cat perching like a giant, benevolent guardian above the city. I hiked up the mountain in December, ignoring a warning sign, to climb onto the lion's head.

Since last October, climbers have hung a succession of giant yellow banners, ranging from six to 28 metres in length, from Lion Rock. Three of the banners read "I want genuine universal suffrage"; another "CY step down". A group calling itself Hong Kong Spidie has claimed responsibility for at least one of the banners, saying in a statement posted alongside a YouTube video that it aims to show that Hong Kong values democracy as much as it does money.

From atop Lion Rock, sweeping views of the city take in buildings that jut out of the landscape like candles jammed into a birthday cake. Interspersed between them are little mounds of green the city has learned to build around. Even up there, the constant rumble of vehicles can be heard.

The lion has watched the city change and develop over the years, and is a historical, geographical and cultural landmark; a keystone that symbolises the "Hong Kong dream" and the "Lion Rock spirit": the belief that anyone can become a somebody if they work hard enough. Now, squeezed by economic pressures such as sky-high property prices and stagnant salaries, many are finding that the dream is fading and the spirit is draining away.

"There's a strong sentiment of a lost generation, of lost hope," says Stephan Ortmann, a professor at City University who has written about the history of student activism in Hong Kong. Jobs are harder to come by, opportunities are diminishing. This sense of hopelessness, he believes, contributes to the mobilisation and political awakening of today's youth, "because they really want to do something about it".

And yet it would be wrong to assume that all of the protesters feel especially hard done by. Cheng, Tong and Char all say they have no financial worries at present.

"But even if [future economic concerns] don't affect me directly, it doesn't mean I won't care," says Char.

Chow, in fact, is a self-professed rich kid. Ming Pao newspaper discovered that his family's wealth totals nearly US$13 million, based on a clothing business that employs 3,600 people in China, Bangladesh and Vietnam. But it is because he has so much, he told Ming Pao, that he feels the responsibility to do something for society.

"When you can bear a higher cost, there's no reason not to come forward," he said.

"This Occupy movement, this civil disobedience movement was something I could afford," says Cheng, who took part knowing she might be arrested. She also put her health on the line by waging a six-day hunger strike.

The first two days were "easy, relaxed", she recalls. It was only when the winter wind blew with it "the smell of lunchboxes from neighbouring tents" that she felt pangs of hunger. Her stomach "actually dented inwards", she says. Her heart rate quickened and she slept poorly. By the fifth day, speaking and walking had become arduous.

"I would take a few steps, say a few words, and be winded," Cheng says.

As she walked off the stage after announcing the end of her hunger strike, she fainted.

The strike undertaken by Cheng and others failed to restart talks with the government. But, although it didn't last nearly as long as the epic fasts undertaken in the 20th century by members of the Indian independence movement and Irish Republicans, for example, Cheng believes it succeeded in showing the determination of the students.

"It brought a message to ordinary citizens: that we, as students, will persevere to do our utmost, to make an ethical complaint to the government. For a fairer electoral system, we take these actions," she says.

As a student majoring in government and public administration, Cheng does worry that her political activities might affect her career prospects.

"I've walked up front. There's a chance of having my details dug up by someone. I [can't even] think about working in the government," she says. "Not that I had any interest anyway."

A popular perception of those who took to the streets is that, in the main, they had little to lose because they were not the brightest or the best.

"Many people think youths who come out and make a movement like this are 'trash youths'," says Tong. "People think that only youths who have 'lost the game' are out on the streets. I don't think that is the case. There are many who play by the rules of the game, but even those who have won … see the problems and want change."

She points to herself - a third-year student majoring in social work at HKU - and protesters from the similarly respected Chinese University, as examples, and says they can't justifiably be called "trash youths".

Tong says she feels stilted by the socially constructed standards used to judge students - that they should some day "be professionals, live a materialistic life and be defined by their academic qualifications" - and sees a distinct lack of choices and opportunities in Hong Kong for all of the city's young.

"We can all see that society can't fulfil our interests, desires and needs, and so when all the youths think this way, we want change."

ON NEW YEAR'S EVE, under a clear night sky and skyscrapers adorned with holiday lighting, a crowd gathered at an oval-shaped plaza by the harbour, several hundred metres from Civic Square, where the umbrella movement had been born three months earlier. Holding yellow umbrellas and balloons, the crowd, several hundred strong at first, eventually growing to more than a thousand, was there to hear Bananaooyoo ("banana milk", in Chinese) perform.

Bananaooyoo is the stage name of Shum Wai-lun, 24, who had been singing on the streets with his guitar throughout the protests. Slimly built with a brow-length fringe and large, round, black-rimmed glasses, he graduated with a law degree from HKU but gave up on being a lawyer because, he says, he found justice, as practised in the corporate legal world, to be lofty, pretentious and empty. He decided to work in the arts instead, as a part-time actor and administrator, substituting his income by tutoring on the side.

"The banana represents positive energy [although it's unclear to many locals how], milk represents childhood innocence," Shum writes on his Facebook page.

Amid political polarisation in a deeply divided society, Hongkongers, it could be argued, are in need of a good dose of each.

On that final night of 2014, Shum sang song after song as the audience swayed, waving smartphone flashlights in the air. Some held up lights against their balloons, rendering them a glowing, translucent yellow. Between songs, the crowd would, from time to time, chant, "I want genuine universal suffrage."

Speaking to these young female protesters has transformed a few of the nameless, faceless blurs I saw on my laptop in Princeton into real individuals, each with their own stories and motivations. Their future and that of their city are intricately bound, and they are driven by a desire for change to take unprecedented risks.

When I ask Cheng what her biggest gain from the umbrella movement has been, she chuckles.

"Gains? I don't think there were too many gains, but there have been a lot of sacrifices," she says. "I've seen tear gas, I've been hit by pepper spray. All these are experiences you don't particularly want to have, but they are life experiences."

Char believes she has come out of the protest movement more empathetic and understanding.

"I can say without shame that having gone through these few months, I think I've become better as a person." She is more willing to put herself in the shoes of others, she says - "even those of opposing camps or factions".

"In terms of legacy, I still don't know. It's not necessarily good. Differences and divides have grown."

For Tong, the movement has fostered personal growth.

"There are things I didn't think I could do before. But after all this, you find that you've become tougher, that you can do it," she says. "Being able to participate in such a symbolic and historically significant movement is in itself a gain. There is pleasure in it, so I have no regrets."

And although, for now, no concrete policy gains have been made as a direct result of Occupy (and the turnout at last weekend's democracy rally suggests people are losing faith with the usual methods of protest), this generation of students has shown that they are no strawberries - and they are not easily bruised.

"For better or worse, there has been a political awakening," Char says.

As midnight approached, Shum launched into a classic from the 1990s by rock band Beyond, titled Golden Age. Holiday lights shone overhead, the brightly lit Ferris wheel turned slowly in the distance and, as a year marked by tumultuous social and political upheavals ticked towards its end, the audience joined in:

"Today there remains only an empty shell

To greet the golden age

Holding on to freedom in the wind and rain

A lifetime of struggling helplessly

Confidence can change the future

We ask, who can do it?"

About the author

Hong Kong-born Mary Hui Kam-man attended South Island School until 2010, then Li Po Chun United World College, in Wu Kai Sha. In 2013, she left her Happy Valley home for a four-year degree course at Princeton University, in the United States. "I haven't declared my major yet but I intend to study politics and Spanish," she says.

Hui chose Princeton because it had a strong sporting background; when she left, she held the Hong Kong junior record for both the 3,000-metre steeplechase and 15km run, and had represented the city four times in athletics events.

Hui says she intends to return to Hong Kong to live eventually: "I plan on working abroad for a few years first, though."