What sparked Hong Kong’s Double Tenth riots

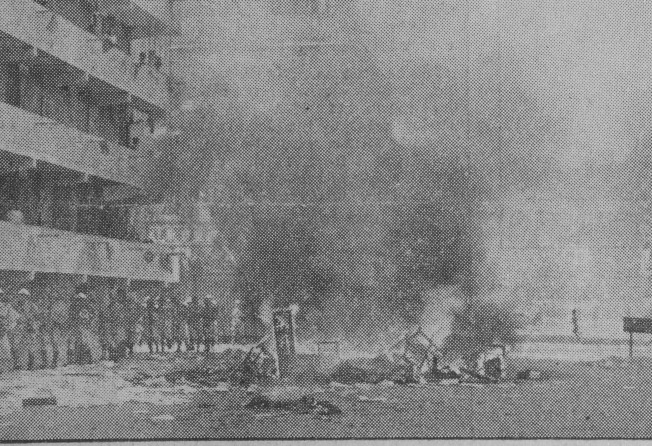

The politically motivated riots that rocked Kowloon in 1956, starting on the anniversary of China's 1911 uprising, left 60 people dead and 500 injured

SIxty years ago this week, northern Kowloon was convulsed by deadly political violence.

Following the Communist takeover in 1949, China had two national holidays. October 1 became celebrated as the foundation date of the People’s Republic and is observed in Hong Kong as National Day. October 10 – popularly known as Double Tenth – is the anniversary of the 1911 Wuchang uprising, which led to the establishment of the Chinese republic, in 1912. This event continues to be commemorated by Nationalist supporters – and in Taiwan. Large-scale public displays of Nationalist flags for Double Tenth were last seen in Hong Kong in 1996, several months before the handover, while low-key celebrations still occur in various places.

The Star Ferry disturbances in 1966, and the Communist-fomented riots that shook the colony for several dangerous months in 1967, are widely evoked in today’s popular memory. Less remembered is the serious unrest that rocked Hong Kong – or more specifically, parts of northern Kowloon – in October 1956. Known as the Double Tenth riots, in reference to the date they broke out, these were provoked by a paid network of Nationalist agents provocateurs and catalysed bitter political tensions that had crossed over from China during the civil war in the late 1940s, and steadily grew in Hong Kong from the early 50s.

In the years that followed the Communist takeover on the mainland in 1949, Hong Kong’s main internal security threat came from the ousted Nationalist regime, by then driven into exile on Formosa (Taiwan). Nationalist-affiliated criminal gangs had flooded into Hong Kong when the Communist victory became apparently inevitable. Vehemently anti-Communist – the new broom on the mainland having swept them from their extortion grounds, with numerous triad members executed – opportunistic involvement by gangs in political violence was predictable.

Localised tensions steadily mounted as ongoing political problems spread into Hong Kong. In one dramatic incident, in April 1955, Nationalist secret agents had blown up an Indian airliner, the Kashmir Princess, which was to transport Premier Zhou Enlai to the Afro-Asian Conference in Indonesia.

The initial spark for the October 1956 flare-up was the removal of a Nationalist flag from the verandah of a resettlement block, ordered by a junior government official. Widespread rioting swiftly broke out, with gangsters joining the fray. Most of the Chinese population of Hong Kong, having escaped China during and shortly after the civil war specifically to get away from political upheaval, offered little or no support to the rioters. With no wish to see tensions between Nationalists and Communists spread, the general public, hitherto politically apathetic, began passing information to the police.

Sham Shui Po was particularly badly affected. Newly built resettlement estates were hotbeds of discontent; many residents bitterly resented their overcrowded living conditions and – not unreasonably – blamed Chinese politics for having forced them into Hong Kong in the first place. Tsuen Wan, then a ramshackle accretion of spinning, weaving and dyeing mills, with appalling living and working conditions, was one of the worst-hit areas – and a Nationalist stronghold.

Hong Kong’s leftist press behaved with hysterical abandon, accusing the “white-skinned colonial pigs” of not doing enough to protect their “compatriots” and issuing veiled threats that Chinese troops would be sent in to do what the Hong Kong Police seemed unable or unwilling to do. The British Army was eventually called out in support of civil power, and soldiers patrolled the streets of Kowloon for several nights. Compensation was ultimately paid by the Hong Kong government to all non-rioters who had suffered in life, limb or property, regardless of their private political sympathies.

Initially provoked by the trivial display of the Nationalist flag on a balcony, by the time these politically motivated riots were over nearly 60 people lay dead, and more than 500 were injured. Four convicted rioters were subsequently hanged for murder.