Why Hongkongers who reject their Chinese identity need a history lesson

They swear allegiance to the city, rather than the country, but ‘Hongkonger’ is an inaccurate and misleading re-categorisation

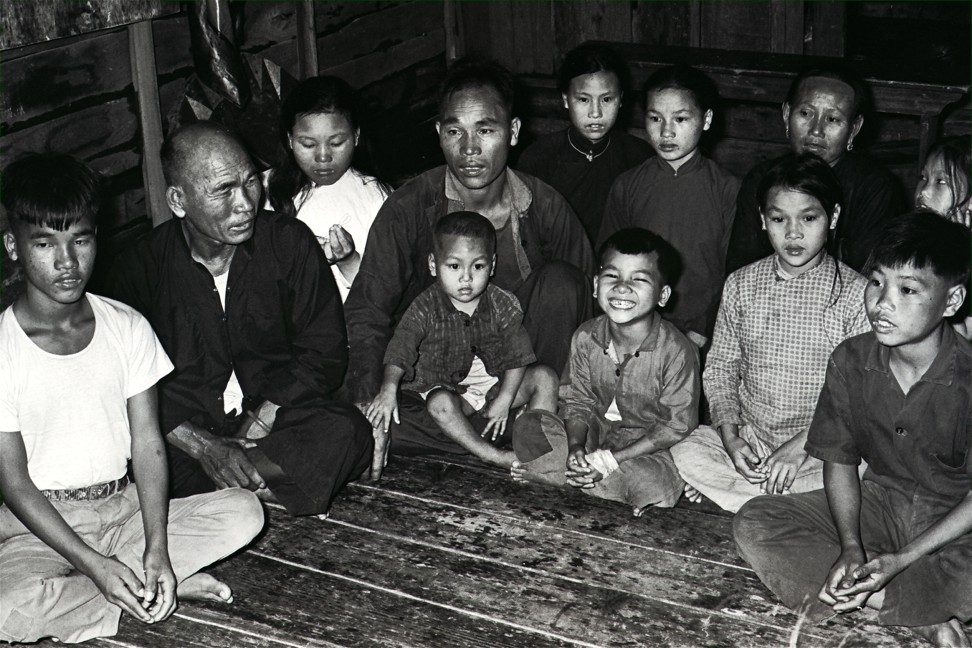

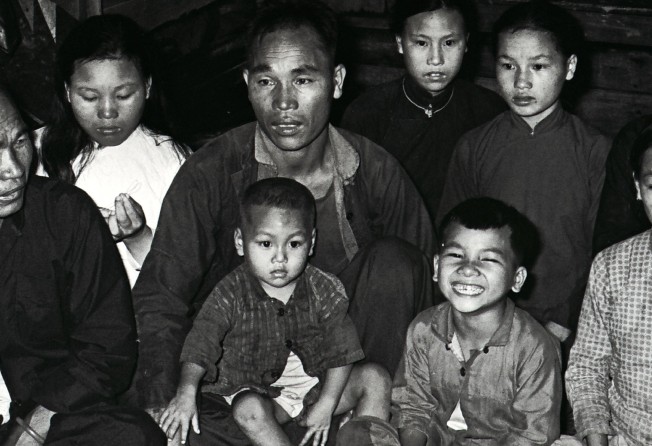

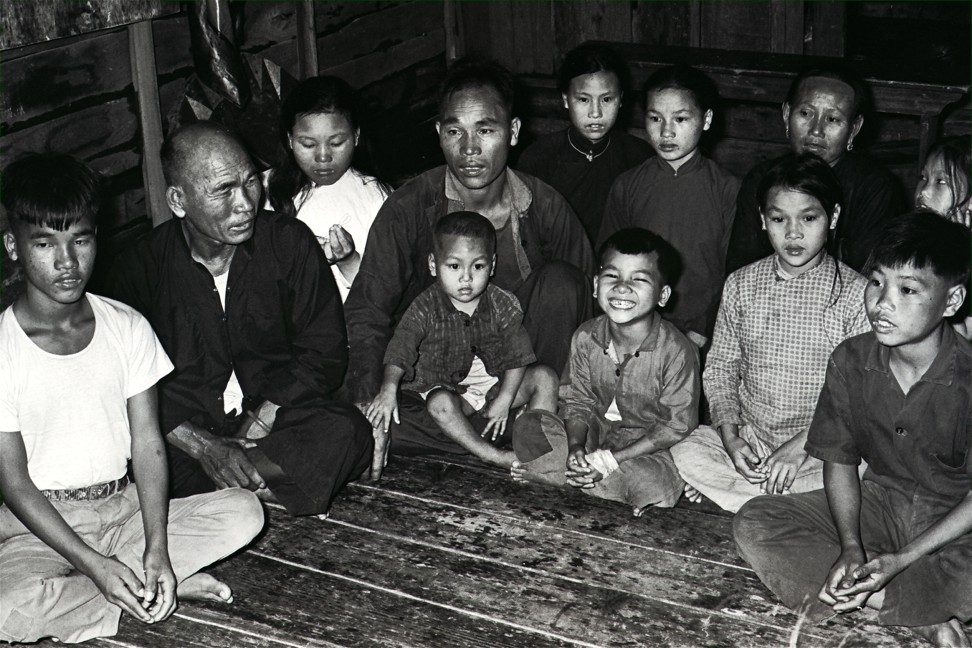

From the mid-17th century until it was administratively fragmented by the Treaty of Nanking (1842), Treaty of Tientsin (1858) and Second Convention of Peking (1898), the southeastern Pearl River Delta was governed as part of Sun On (“new peace”) county, also at various times known as Po On (“precious peace”) county. This district incorporated what is today Shenzhen (north about as far as Shenzhen Airport), the New Territories, the outlying islands, Kowloon and Hong Kong Island.

As Hong Kong edges ever closer towards being, for most practical purposes, the Xianggang district of Shenzhen, many who live here are feeling profoundly uncomfortable. That this inexorable process is now happening faster than most are prepared to openly acknowledge is obvious to any clear-eyed observer. What follows is a brief history lesson for Hong Kong’s growing legion of identity politicians, and those who misguidedly believe that Hong Kong and its people have a history stretching back some 1,400 years, manifest in forms and continuities recognisable to modern residents.

In much the same way, there were no Italians in the 14th century, Germans in the 18th, or Singaporeans in the 19th. There were Venetians and Florentines, Prussians and Bavarians, and the disparate confluence of peoples from everywhere from Massachusetts and the Levant to the Malay archipelago, southern India, China and Japan who had settled around the Strait of Malacca. Woolly postmodernism, in which all “opinions” are “valid”, lies at the root of this inaccurate and dangerously misleading re-categorisation.

As the “one country” component of the “one country, two systems” formula becomes increasingly paramount in Hong Kong affairs, it is vital to understand the “Hongkonger” concept in the context of the relatively recent past, and how previous local identities – or the historical lack of them – have been reimagined to suit contemporary political agendas.