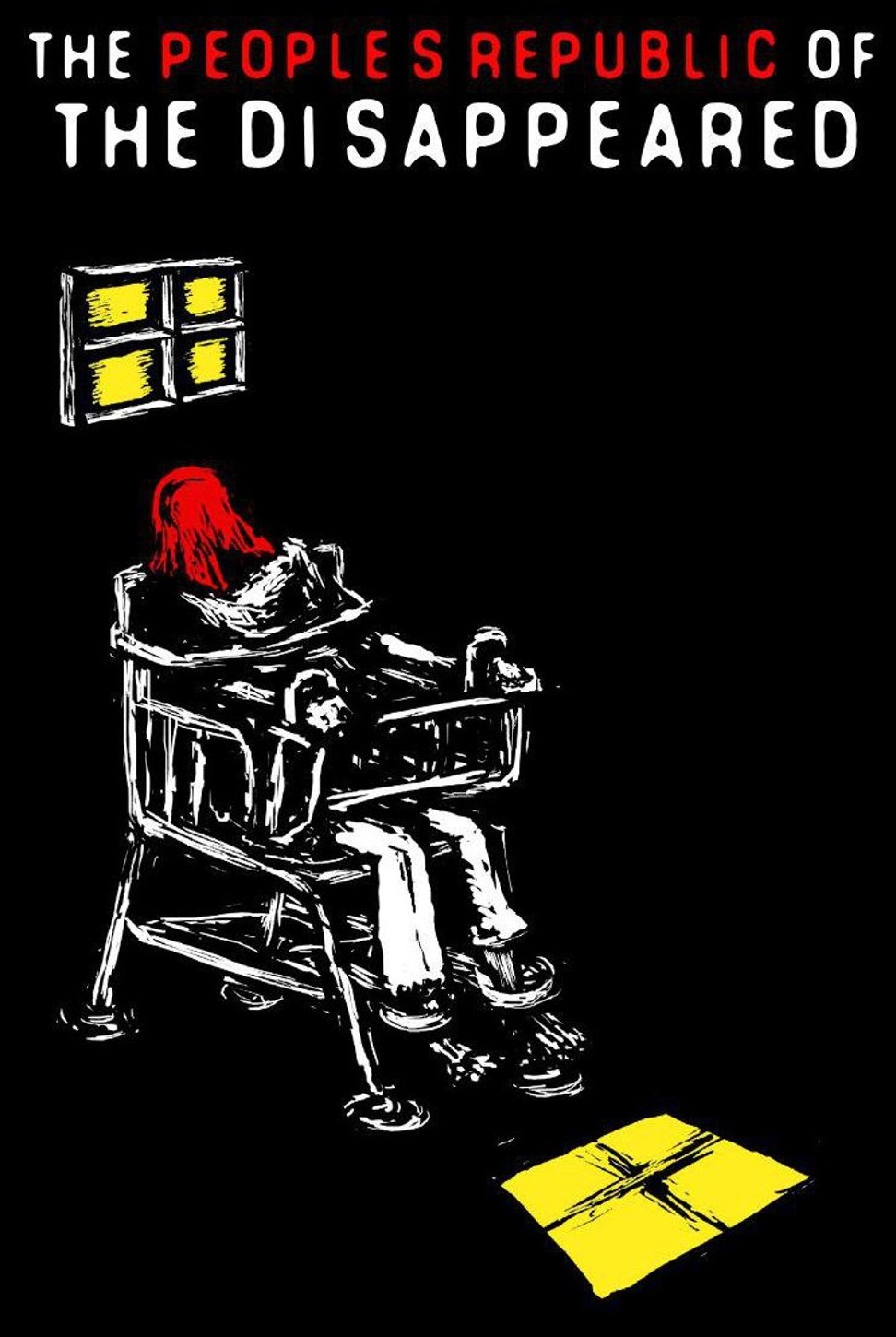

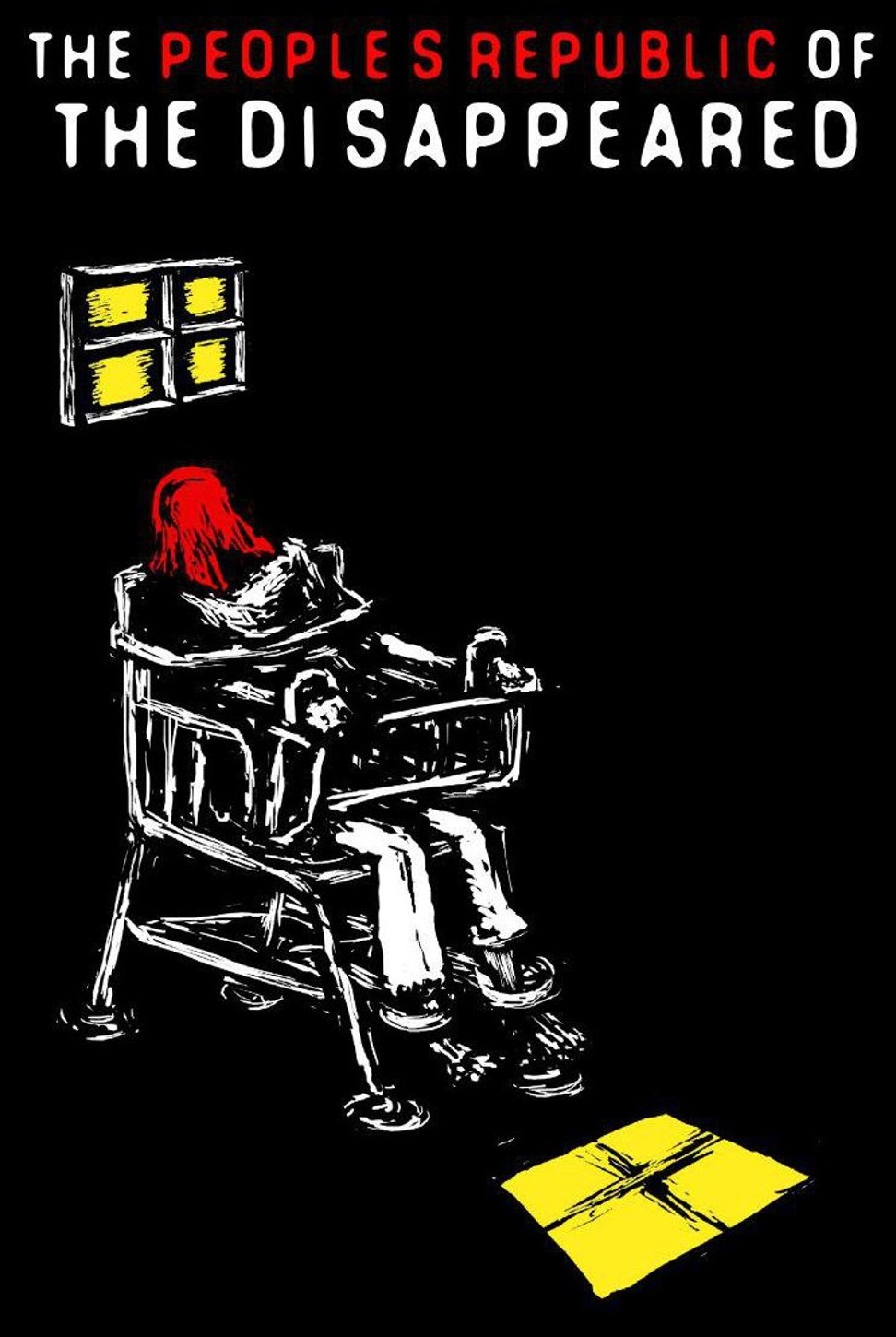

Abductions by Chinese authorities detailed in US-published book

The People’s Republic of the Disappeared documents the brutal techniques used on civilians and rights activists under the state’s ‘residential surveillance at a designated location’ detention order

“Residential surveillance at a designated location” doesn’t sound so bad. It hints at house arrest, the sort of detention you might get if your transgression doesn’t warrant a prison sentence or perhaps while the authorities determine the nature of your crime. But if those who have provided first-hand accounts in The People’s Republic of the Disappeared are to be believed, it is far more sinister than that.

Published in November, the book is edited by Michael Caster, a human rights advocate and senior adviser to the Chinese Urgent Action Working Group, which states its mission as being to strengthen the rule of law in China. The book brings together the accounts of 12 people who have been held under RSDL, a form of detention introduced into Chinese criminal law in 2012, with the amendment of Article 73 of the Criminal Procedure Law, to allow the authorities to detain people for reasons of state security or terrorism.

Sui’s account comes towards the end of the book, by which time the reader is familiar with RSDL, which, it is alleged, typically begins with an abduction and quickly descends into physical and psychological abuse, isolation, threats to family and friends and sleep deprivation.

“Early on the fifth or sixth morning of sleep deprivation, the tiredness started to hit me. My consciousness felt vague, followed by a pain I felt all over my body. It was like being roasted by a fire, while at the same time feeling extremely cold. It was a kind of pain that I had never experienced before. Faintly, I felt that I was dying,” writes Sui, who is known for his work defending other rights activists, including fellow lawyer Guo Feixiong.

I had the right to ask for a lawyer, but I did not have the right to receive a lawyer. I had the right to meet embassy personnel, but the authorities could make me wait as long as they wanted before allowing me to meet anyone

RSDL is not reserved for only Chinese citizens – the remit is broad and anyone viewed as a threat to the Communist Party can be held. Swedish activist Peter Dahlin contends that he was kidnapped at his home in Beijing in January 2016 and held in a secret prison for 23 days. In his account he describes his abduction and how he was read a long list of rights that was, in effect, a list of things he was allowed to ask for, but not get.

Dahlin’s girlfriend, Pan Jinling, was also arrested, despite the fact she was not a human-rights activist or lawyer and knew nothing of her boyfriend’s work. She describes being kept under 24-hour watch by two guards sitting in her cell and taking notes on every small move she made.

All the money the government wasted on keeping me for a month, the people’s money. For what? To show strength?

She did the maths – if each guard was paid 6,000 yuan (HK$7,130) a month and she was inside for almost a month, the guards alone would have cost 60,000 yuan. Add to this the facility and food and the wages of the teams of interrogators and the cost escalated – a huge amount considering it was for someone who wasn’t seriously thought of as a criminal.

“All the money the government wasted on keeping me for a month, the people’s money. For what? To show strength? But how powerful could they really be if I was seen as a threat? It made me smile a little inside,” Pan writes.

Long-time legal rights activist Bao Longjun was one of the first to disappear in what became known as the “709 crackdown” against rights lawyers in the summer of 2015. He describes being told he had to ask permission for everything he did, including to swallow.

“If even the smallest whisper came from my lips as I recited poetry, as I often did to myself in times of extreme boredom, they would stop and reprimand me. ‘You’re not allowed to move your lips,’ they would say,” Buo writes.

Published in the United States, needless to say, the book has not been released in mainland China or Hong Kong.

“Confronting China is no easy task but it is hoped that this book will serve as a wake up call to the extent of China’s war on human rights,” writes Caster.