From bestiality to Beyoncé: Umberto Eco waxes lyrical in a final interview

Three months before he died, the Italian literary giant and professor of semiotics took Gaby Wood on a whirlwind tour of his thoughts, which touch on everything from bestiality to Beyoncé.

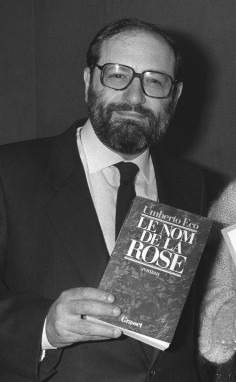

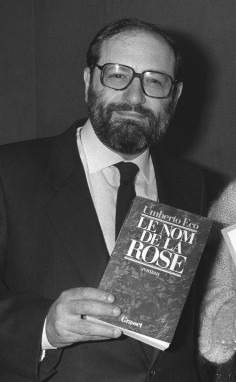

Umberto Eco, the Italian philosopher who wrote bestselling novels including The Name of the Rose, died on February 19, aged 84. This interview was first published in November last year.

When Dan Brown published The Da Vinci Code, in 2003, Umberto Eco didn't think, as others did, that Brown had ripped off his own earlier bestsellers. Eco went one step further: he took credit for inventing Brown altogether.

At 83, Eco has the physical appearance of a long-term armchair detective. When I arrive at the London hotel bar where we have arranged to meet, he already looks well settled. Eco orders steak tartare and a couple of glasses of chablis.

At first I feel I have positioned myself for a tutorial with the great professor, whose heavily accented English immediately suggests a commanding performance. But the background music is so loud that Eco is forced to lean sideways towards me, and I'm afraid he will spill out of his chair.

Our conversation takes in, through no plan of mine, subjects ranging from Agatha Christie to sex with animals, and a comparison of fascist Italian leader Benito Mussolini with Beyoncé.

Later, I realise that its faintly absurdist quality must have been partly due to the fact that Eco, tired of asking me to repeat my question, had occasionally decided to answer a different one.

At one point, for instance, we find ourselves talking about a television programme he loves, Starsky and Hutch. If you were to write a television series, what would it be? I ask him.

"You cannot do everything," he says. "You know the Latin proverb Ars longa, vita brevis? I was asked by a gay magazine, have you had homosexual experience? I answered: Not yet. Because ars longa, vita brevis."

Was he counting the homosexual experience as part of art or life, I wonder aloud.

"You have only 80 years. You cannot try also bestial coitus. It takes too much time."

While I am taking this in, Eco adds: "There is another reason why I never tried to direct a film. Because I am impatient. In a film, if you need an elephant and the elephant is not there, you have to wait two days. I cannot wait two days for an elephant."

You could make a film without elephants, I suggest. Eco says: "I should make only films without elephants." And so on.

Though he became an international literary celebrity with the English-language publication of The Name of the Rose in 1983, he has mostly been an essayist, as well as a professor of semiotics and a prolific writer of newspaper columns in Italy.

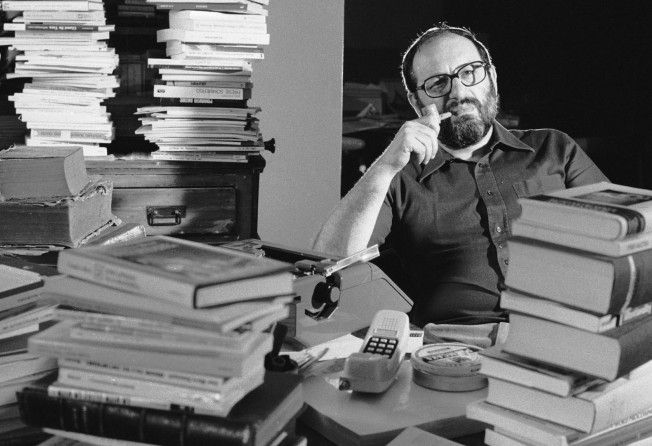

Because The Name of the Rose made him wealthy, he has an apartment in Milan and a 17th-century manor in the countryside, both filled with rare books. Because he is a respected professor, he has not given up, despite his retirement, his Renaissance office in Bologna, an oval-shaped room much older and more beautiful, he says, than the Oval Office occupied by the president of the United States.

His new book, Numero Zero, takes on a profession he has both worked in and criticised for most of his adult life: journalism. Narrated by a middle-aged ghostwriter and "compulsive loser" who is hired for a vanity project, it follows the founding of a phoney newspaper in Milan.

The newspaper is never meant to exist: it has been commissioned by a small-time tycoon - a would-be Silvio Berlusconi - and is designed to function only as a threat. Backdated issues will fearlessly expose corruption since proven to be true, formulating it in the future tense. Rather than report, the newspaper will pretend to predict - it's called Domani (tomorrow); its leaks are supposed to be "oracular" - and its seemingly spooky prescience will render the corridors of power so anxious that the tycoon will have all the blackmail tools he needs.

The beauty of a retrospective newspaper is that you know exactly what you will find, and thus are entirely able to control the news. The paper's editor instructs his staff with ingenious daily workshops on denial and defamation, in terms that will be comically familiar to anyone who has ever worked on a newspaper themselves.

They are always returning - there are no more fascists, but there are racists, people who are anti-immigration, anti-Europe

"You know," says Eco, "some important Italian journalists, like the founder of La Repubblica and the former director of Corriere della Sera, said: 'OK, our papers are not that bad.' But there are many features that belong to every newspaper."

Some newspapers recognised themselves in the novel and didn't know what to do, Eco says (though it's unclear how he knows this).

"Because if they attacked the book they would have confessed … So they spoke very well of it, but said it was obviously referring to somebody else." It sounds like an excellent strategy for getting positive reviews, I suggest.

"I was a little bit irritated by the German reviewer who read this book as a book on Berlusconi," he says. How can it not be about Berlusconi, I ask. Eco replies that his fictional tycoon "can be Berlusconi but he can also be Murdoch, or Trump. I mean, the world is full of people like that. Certainly, you can see some elements of Berlusconism, but my target was larger."

The review published by the South China Morning Post concluded that "although Numero Zero takes place in 1992, Eco may as well be describing our current journalistic landscape of cheap shots and clickbait. How do we process the overload? The implication is that we can't. Not only that, but the whole purpose is to overwhelm us, to keep us from understanding how everything adds up."

In his 2004 book On Literature, Eco explained that he wrote fiction between the ages of eight and 15, and didn't return to it until he was nearly 50. "Of this output," he writes, "I have retained only one finished work, of indeterminate genre."

His early writing and drawing was coloured by the books he devoured - from comics to P.G. Wodehouse and Dante - and the influence of these childhood preoccupations can still be felt in his later work.

The phrase "of indeterminate genre" itself is telling, since Eco loves a pastiche. As a semiotician, he has analysed a number of genres with zest, and as a novelist his forte is a pile-up of wide-ranging references and in-jokes. For instance, his novels all contain characters named after typographical fonts - Baskerville, Garamond, Bodoni, Palatino, Colonna, etc. His grandfather was a typographer.

Most of his writing, in fiction and non-fiction, has a ludic quality, whether his subject is medieval monks, conspiracy theories or WikiLeaks. The Name of the Rose had at its core the notion of laughter as a dangerously powerful force, and it's as if Eco has set out to prove, again and again, that the structure of a detective novel is exactly the same as the structure of a joke.

Numero Zero is a thought experiment along these lines. It has none of the breathtaking scholarship, dizzying ideas or formal style of his early novels, and is less than a third of the length, but it has a fundamentally jocular and quietly political premise. Without spoiling the plot, it can be revealed that Numero Zero becomes a murder mystery. The main scoop concerns Mussolini, and a theory that he survived the war, hid in Argentina or the Vatican and directed post-war politics from there.

This is the latest in a long line of fake conspiracies that have fascinated Eco. Still, you don't need Mussolini to be alive to feel his influence on politics. Though the conspiracy is implausible, the point, surely, stands?

Eco's idea about Mussolini's survival is an elaborate way of saying the spirit of fascism lives on. "Yes, OK," says Eco. "Good reading. A+."

I mean, is that what you think, I ask.

"Yes. Certainly. They are always returning - there are no more fascists, but there are racists, people who are anti-immigration, anti-Europe. I think 51 per cent of Italians are Right-oriented. Then, for the 49 per cent, the Left has self-destructed and offered the Right the possibility of winning. There you have the curse of Italy: one half fascist and one half suicidal."

Eco grew up in the era of Mussolini - as a child, he wore the uniforms, attended the rallies and dated his schoolwork, for instance, "Year XXI of the Fascist Regime".

"All around us there was a continuous celebration of the body of the dictator," he recalls. "In schoolbooks, in the movies, in the streets. Maybe it happens now with Beyoncé. Yes, because the real idols are from show-business. There was no showbusiness then, there was only political business."

But Eco was never enamoured of the dictator. He thought: "Am I a bad boy, incapable of loving Mussolini? Maybe I have a corrupted mind."

Eco has been looking back on his early years lately, for a project he describes as "the most difficult job of my life".

An American book series called The Library of Living Philosophers has proposed a volume about his work. Since the series began, in 1939, it's covered John Dewey, Bertrand Russell, Albert Einstein …

"And now," says Eco, "due to general intellectual crisis after the Lehman Brothers, they have nothing better and are doing it for me." His response to them?

"Be fast, because the series is on living philosophers, not on dead ones."

DT Review