By Liu Cixin

Tor

Death’s End, the final instalment of author’s Three-Body trilogy, leaves the Communist Revolution narrative behind as it propels mankind ever further into space

All eyes seem to be on China’s science-fiction writers. In August, the 2016 Hugo Award for best novelette went to Folding Beijing , a dystopian work written by 32-year-old Tianjin native Hao Jingfang, beating out none other than horror master Stephen King. And in 2015, the Hugo for best novel went to The Three-Body Problem, the first volume in a mind-expanding trilogy that starts with an alien invasion threat discovered during China’s Cultural Revolution.

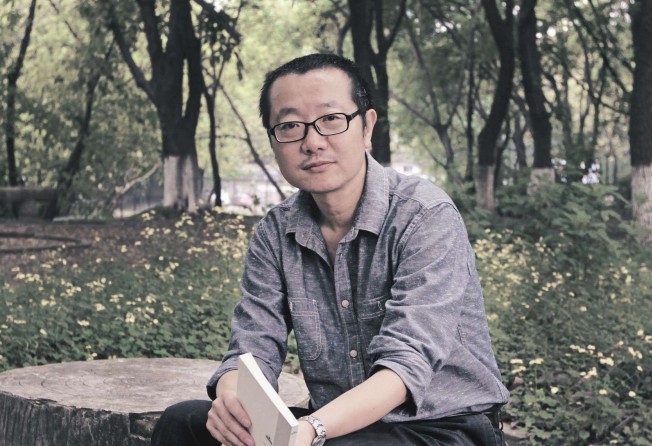

That novel introduced English-speaking readers to the creative mind of Liu Cixin, China’s most beloved science-fiction author and a multiple-award winner. Last month’s English-language publication of Death’s End, the final instalment in the trilogy, cements Liu’s position as a leading sci-fi mastermind not only in China, but around the globe.

The 53-year-old Liu’s books have achieved success in part because they embrace the pure fundamentals of science fiction as a genre. That is, they contain wildly imaginative ideas about humanity’s future grounded in all manner of bizarre and brilliant scientific concepts.

In Death’s End, Liu presents another work of pure sci-fi bursting with concepts seemingly taken from textbooks on physics, astronomy and cosmology. These hard-science ideas drive the story and its cast of characters throughout the cosmos and – as the novel’s name implies – towards the end of the universe.

As the story opens, an uneasy peace exists between Earth and the alien invaders, known as the Trisolarans (because they hail from a system with three suns). In the previous book, humanity won a victory against the Trisolarans by deploying a strategy known as dark forest deterrence.

Earthlings, though vastly inferior in terms of technology, were able to prevent an imminent Trisolaran invasion by threatening to reveal the location of their enemy’s solar system to other alien civilisations. If their location is revealed and they are brought out of the “dark forest” of space, the Trisolarans could face destruction. Liu clearly revels in bleak sci-fi fare, a far cry from the positive, comforting visions of the future in which extraterrestrial civilisations “come in peace” seeking trade and knowledge.

The plot is driven by a range of topics: lightspeed travel via space curvature propulsion, multiple universes that exist outside of time, cities in space powered by tiny nuclear suns, and even a two-dimensional world where all life is perfectly flat.

That’s not to say that Death’s End is entirely satisfying, or even superior to the trilogy’s first two novels. As with The Three-Body Problem, the narrative features bland “saviour characters” who occasionally wake up from extended cryogenic hibernation to set things right for humans – or to mess everything up all over again.

This is a definite step back from the reluctant, brooding hero of The Dark Forest, Luo Ji, who appears again in this novel, albeit much older and wiser – and now sporting a long, flowing white beard.

The best-drawn character in Death’s End is perhaps Sophon, an android wirelessly controlled by the distant Trisolaran army. Sophon epitomises the rigid, militarised culture of the aliens, which has led to many technological breakthroughs – a stark contrast to the care-free, lazy culture that technology has brought to Earth.

While it makes no moral pronouncements, Death’s End invites readers to weigh the potential freedom and fear of life among the stars against the safety of life on Earth; and to weigh the pursuit of grandeur through knowledge against a beautiful yet ignorant complacency.

Gone are the first book’s historical references to the Communist Revolution, replaced with pressing struggles in outer space as the narrative moves away from Earth, bit by reluctant bit.

Another grand idea Liu lets us chew on is how life in space, separated from Earth, might fundamentally alter humanity. As a captain from the international star fleet says, “When humans truly enter space and are freed from the Earth, they cease to be human. When you think about heading into outer space without looking back, please reconsider. The cost you must pay is far greater than you could imagine.”

Eventually, humanity must decide whether to hunker down in its home solar system, or spread its wings and leave it all behind.

Liu handles the novel’s jump-cuts across time – some involving a few years, others much more – in a way similar to that Isaac Asimov uses in his Foundation saga, which also spans a massive period. Thanks to advances in hibernation technology, Cheng and other central characters can sleep through numerous ages and awaken to witness the results of decisions they made eons before.

Like a science laboratory, Liu’s sci-fi finale is packed with imaginative experiments such as these. Many amazing ideas are tested, poked, prodded and stretched to breaking point to see what would happen if they were applied to Cheng’s world.

As Death’s End draws to a close, humanity and the Earth have come a long way since page one of The Three-Body Problem. And that long journey makes for a fantastic read.