by Gabi Martinez

Scribe

Jordi Magraner spent 15 years in Chitral in search of a Himalayan Yeti, a quest that ended with his murder in 2002. Seven years later, journalist Gabi Martinez followed in his footsteps, and the result is a riveting book

“Some stories are hard to believe, and this is one of them,” writes lauded Spanish author Gabi Martinez near the start of In the Land of Giants, his 11th book and an inspired telling of an uncommon story.

It’s a story that is fable-like in its outlines, yet unmistakably grounded in some of the harsher realities of our times.

Indeed, from the outset, writes Martinez, there was “something marvellous” about this story of renowned Spanish zoologist Jordi Magraner, who, one morning in August 2002, was found with his throat cut in Pakistan’s Chitral region, where he’d lived for 15 years. Magraner had been searching for the mythical barmanu – as locals call the cryptid of the Hindu Kush. The morning after his death, the newspaper headlines all said the same thing: “Yeti hunter found murdered.”

Seven years later, no one had been convicted for his killing – nor has anyone since – and rumours still swirled around the 44-year-old Spaniard’s slaying, with some newspapers hinting at the involvement of secret government agents, others that it was a crime of passion. Even the few reported facts of his life seemed to have mythical dimensions; revered by the Kalash, an ancient pagan people of the Hindu Kush who had buried his body with honour, Magraner had also been involved in humanitarian convoys in Afghanistan as well as with Alliance Française in Peshawar.

There were also suggestions he had had dealings with Ahmad Shah Massoud, the region’s legendary anti-Taliban resistance leader. But for Martinez, unravelling the mystery and, indeed, the marvels of the zoologist’s life and death would prove as dangerous as it was irresistible. It would mean retracing the footsteps of the yeti hunter into Pakistan’s northern valleys – the region that, in 2009, was the operational base of al-Qaeda.

It’s difficult to say which is the more potent in this riveting tale of obsession, adventure and murder, Martinez’s vivid portrayal of the myriad people involved or the age-old allure of the Hindu Kush itself, which is like a living character in the narrative. Its majestic summits, said to include more than 40 higher than 6,000 metres, are mostly anonymous save for the fabled Tirich Mir, the tallest of “the rooftops”, and form a chain enclosing “Edenic lakes, glaciers, gullies and virgin forests where a different kind of life is possible”, writes Martinez.

“Legends about which nothing is known are glimpsed on the other side of this geological palisade that preserves settlements which are barely more than medieval – legends that tell of Alexander the Great’s descendants, of animals facing extinction and furtive creatures that hide to escape from man.”

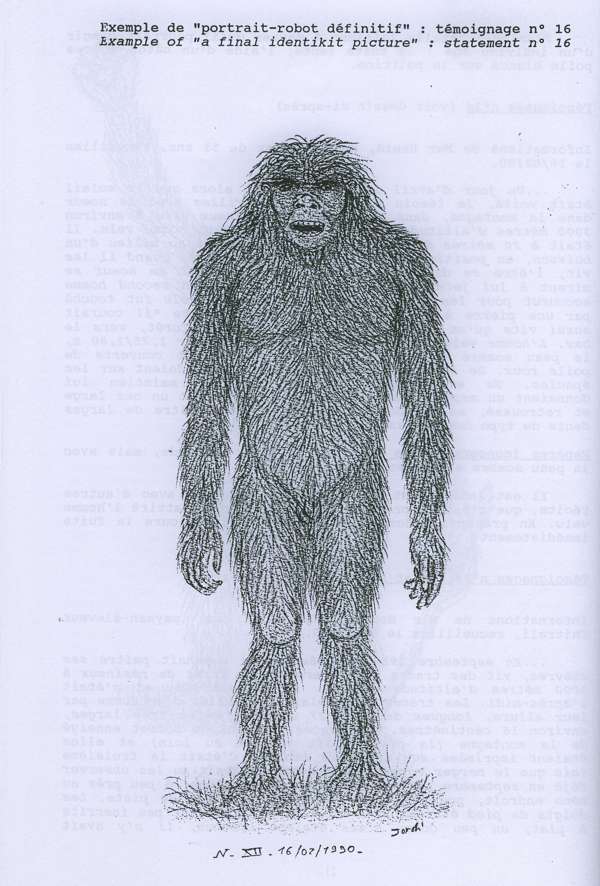

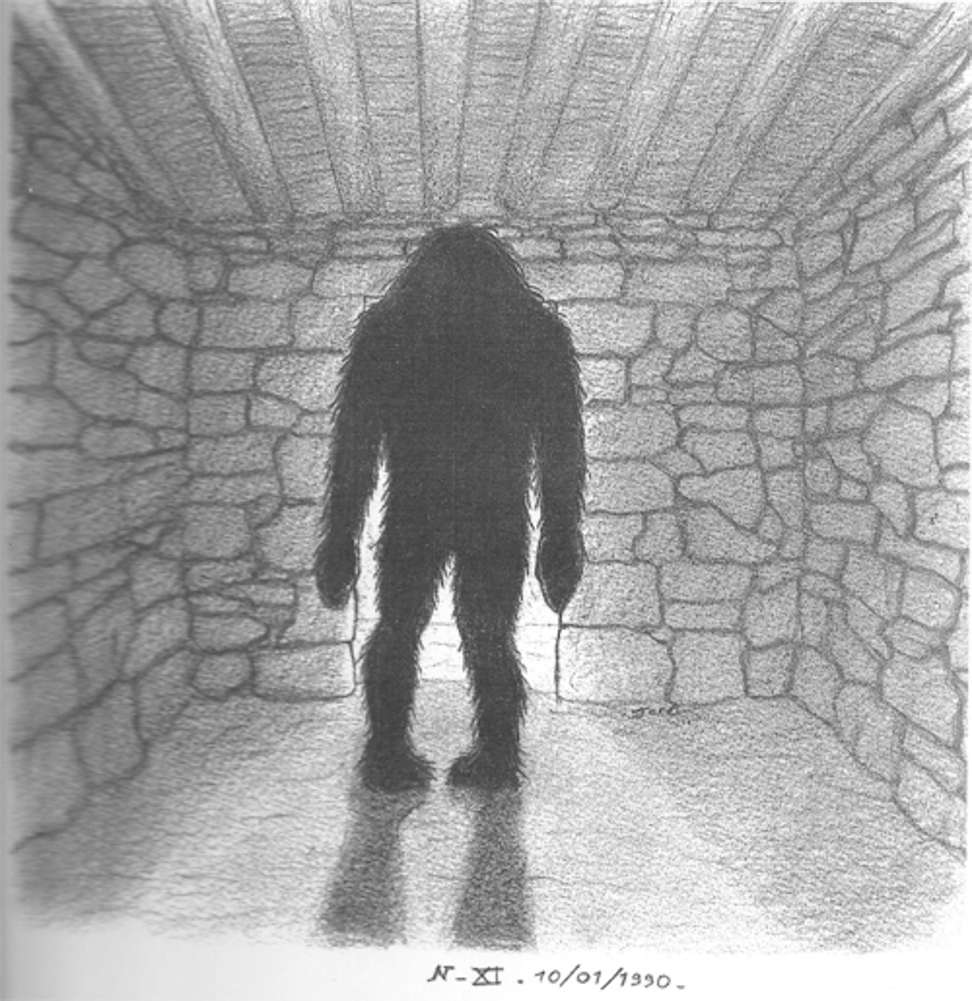

None is more elusive than the hairy bipedal monster known as the barmanu, which lured Magraner to leave his home in the suburbs of the French city of Fontbarlettes, in Valence, for the Chitral in 1987, aged 29. Indeed, the notion of “monster” – be it human, animal or a mixture of both – is a metaphor that haunts In the Land of Giants, with Martinez seaming his narrative with references to relict hominids, from Carl Linnaeus’Homo monstrosus and the legends of “bigfoot” and “the wild man” to the theories of Bernard Heuvelmans, the Belgian-French scientist explorer who founded cryptozoology and co-authored the 1974 book L’homme de Néanderthal est toujours vivant (“Neanderthal man is still alive”) – a book that was to have a profound influence on the young Magraner.

Long before he set out for Pakistan in search of the barmanu, Magraner had established a correspondence with Heuvelmans, who had demonstrated that many animals discovered in the 20th century, such as the coelacanth or the Paraguayan peccary, were located only after conversations with indigenous peoples.

Sex and money, along with notions of monsters and identity, are recurring themes. While empathising with Magraner’s constant struggle for financial and institutional support, Martinez writes: “Most of what excited me was the certainty with which Magraner had surrendered his life to a cause with no apparent meaning, which, contrary to all predictions, would open up unimaginable rifts in the French scientific establishment.”

Be it those rifts or others that the increasingly contradictory and volatile Magraner opened up with his friends in France and in the Chitral, or with his beloved young Nuristani Muslim protégé Shamsur, Martinez leaves no stone unturned in his quest to illuminate the fault lines of Magraner’s life, as well as the wellspring of his hunger for a life outside the conventional.

Born in Morocco to Spanish parents, the fifth of six siblings, Magraner lived in Valence with his family from the age of six. He had demonstrated a preternatural affinity with nature from a young age, developing a particular interest in amphibians and reptiles. When he set out for Pakistan’s northern valleys that December of 1987, with photographer and childhood friend Yannick L’Homme, he was in search of a new way of life, a way of living with nature, as much as the new species of birds, reptiles and amphibians he told the Valence newspaper he was planning to study.

He didn’t emphasise his main objective, to find traces of something humanoid but not human, because he was not yet convinced about the existence of relict hominids.

Magraner collected 50 accounts of first-hand sightings, personally documented large humanoid footprints and was known for being the first to do so in the Hindu Kush. Yet the magnetic pull of this book lies not in barmanu sightings but in the way the zoologist’s outsized character and mythic obsessions play out against the mounting political and religious tensions of the time – and in the way Martinez clarifies the complexities of the region’s tribal dynamics, the ongoing impact of the war in neighbouring Afghanistan on the region and the immense hardship of those condemned to live in it.

As one of Magraner’s Kalash friends, a hotel keeper in the Chitral, tells Martinez late in the narrative: “How do you shake off a feeling of poverty when you know you are poor and you have no possibility, not at all, of changing that situation?”

It was ultimately the plight of the Kalash, and his pledge to save them from extremist Islamism, that had kept Magraner in Pakistan, despite death threats. Yet even the shocking revelations about his murder that come toward the end of the book, along with previously undisclosed details of the slaying of his 12-year-old Kalash servant, Wazir, whose body was found the following day, don’t fully lift the veil of mystery surrounding his death. Nor do they diminish the grandeur of Magraner’s dreams, or his bravery in pursuit of them.

Yet in writing of the outsized life of Jordi Magraner, the only person to have his name incised on a headstone in the Kalash cemetery, Martinez is also writing about the nature of storytelling itself, its potent and enduring pull on our lives. “How far does the imagination reach?” he asks near the end. “How far should we trust it?”