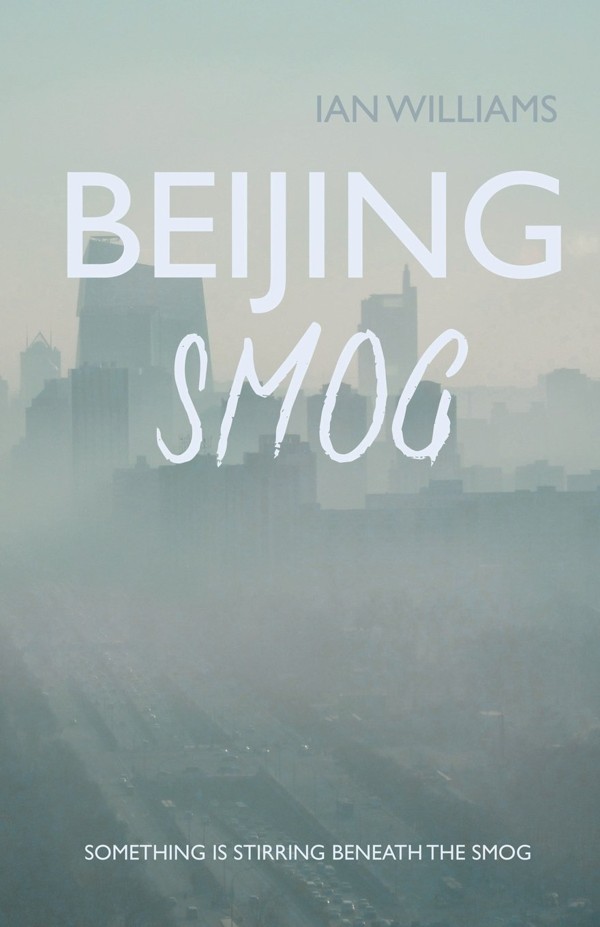

Book review: Beijing Smog - biting satire of corruption and repression in modern China

Ian Williams has reported on China for more than 20 years and his debut novel has a lot of fun exploring the cynicism of the country’s Kafkaesque system

Beijing Smog

by Ian Williams

Matador

A biting satire of modern China, Beijing Smog takes just about every zeitgeisty theme imaginable, from fake news and civil disobedience to corruption crackdowns and Ferraris crashed by playboy sons of Party bigwigs, and weaves them into a twisting tale of espionage, cybercrime and high-stakes double dealing.

Beijing Smog tells the interlocking tales of three characters: Wang Chu, a geeky, entrepreneurial, video-game-addicted university student who lives his life online; Chuck Drayton, a bluff, mordant, distinctly undiplomatic US diplomat who has fallen into the job of cybersecurity expert only because everyone else knows less than he does; and Anthony Morgan, a British business fixer who is remorselessly Micawberish about the Chinese economy’s prospects in public but expresses his true feelings in a series of gloomy tweets via a VPN as @Beijing_smog. Well-connected, confident and wealthy, Morgan is also naive and a bit of a buffoon.

Williams beautifully captures a digitally alienated generation, unable or unwilling to communicate in the real world, and bereft when their internet access is cut off

Starting with the assassination of an anti-corruption official at a concert in Beijing, the labyrinthine plot has Drayton on the trail of another senior official, and he requests the assistance of Morgan, whose inquiries rattle the wrong cages. The action careens between Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen and Harbin, with an extended section set in Hong Kong and the usual casino shenanigans in Macau. Williams nails Hong Kong and its people, and Morgan is able to identify Hongkongers in mainland China by their “restless fingers” constantly jabbing at the close button in a lift.

Wang, meanwhile, uploads a series of images to social media, including one of a stick alien that inadvertently becomes an anti-government meme. In his flippant postings, which are repeatedly taken seriously, Wang suggests that aliens have taken over the government and are attempting to weaponise smog, leading to high-level US government discussions about the possibility of doing so.

Wang is breezily unconcerned that his and a million other social media users’ game of whack-a-mole with online censors might turn into anything more sinister, and his jokey postings also put him on the wrong side of Cantonese gangsters led by a Macau junket operator. Although tech-savvy, Wang is no less naive than Morgan about the potency of online activities. But the virtual world can be just as dangerous as the real one.

The book’s young characters claim that protesting against the state is pointless, but they retreat into an online world less out of apathy than because it is more palatable than reality. Williams beautifully captures a digitally alienated generation, unable or unwilling to communicate in the real world, and bereft when their internet access is cut off.

Not that Wang is unaware of the corrosive effects of a life lived virtually. Of an industrial chemical accident when the student was a child in Harbin, the author writes: “Back then not so many people were online, and nobody ever knew for sure what had happened. Wang reckoned that if it happened again today then everybody would know, or at least they’d think they knew.”

All information in Beijing Smog is untrustworthy, degraded, manipulated, spun. Most people know this, but act as if they don’t. The plot rattles along on a series of misunderstandings, untruths and coincidences, sometimes bordering on the farcical, while the three interlocking narratives allow plenty of room for dramatic irony.

The book skewers both the inanities of propaganda-speak and the naivety of foreigners doing business in China, blinded to dangers – including professionalised intellectual property theft – by the dollar signs in their eyes; everyone is outsmarted by the Chinese authorities, including US National Security Agency hackers, who aren’t quite as clever as they like to believe.

Beijing Smog is full of stories of corruption and wrongdoing, piled almost casually one on another. “Corruption is the system,” one character observes. It has been internalised by the young, who are unconcerned about the ethics of buying answers to exam questions in advance. Wang outsources his applications to US universities, getting his essays written and his references faked.

The cavalcade of outrages and injustices at times seems gratuitous, as if the author is trying to squeeze in as much good material gathered in his working life as possible. Wang’s parents’ radicalisation, after the authorities crack down on their church, feels particularly shoehorned in.

There’s a tendency to over-elaborate, with the same story effectively told twice in places, as well as the habit of reintroducing characters and places the reader already knows. And a cautiously upbeat ending is a jarring departure from the bracingly cynical tone that has gone before.

For all that, Williams is a fine descriptive writer, able to conjure a detailed scene in a few sentences, while his prose is sparky, knowing and immensely readable. There is deadpan humour throughout, particularly where Wang is concerned, as characters normalise the unconscionable, and a casual absurdism in the half sinister, half ridiculous entanglements with bureaucracy that is worthy of Joseph Heller.

As with the dissenters in Beijing Smog, humour and ridicule are its author’s most powerful weapons.