Chinese-American author Jenny Zhang’s taboo-busting short stories mix sweet and rancid

Zhang explores juvenile sexuality and the way trauma is passed down the generations with a strong authorial voice undercut somewhat by a certain repetitiveness in content and themes

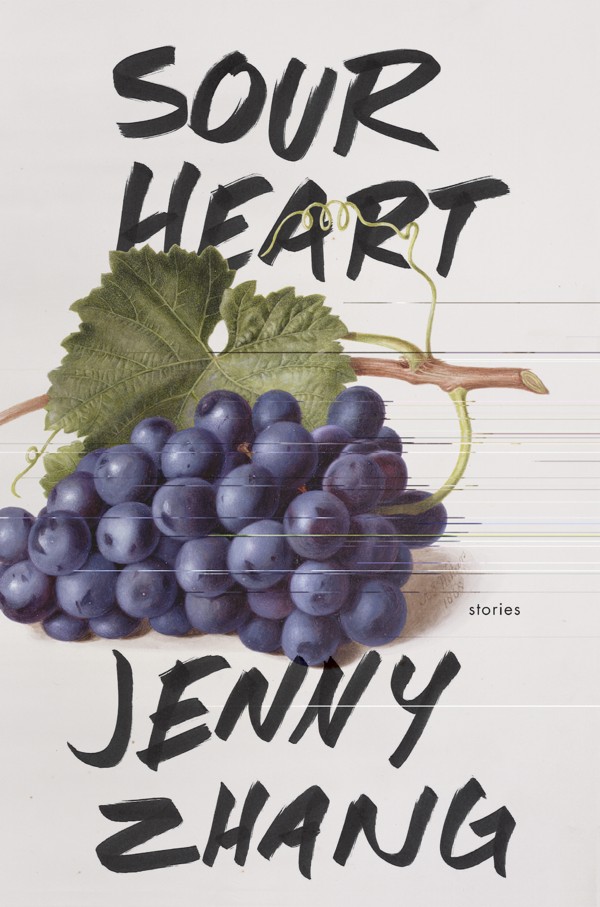

Sour Heart

by Jenny Zhang

Lenny

Shanghai-born, New York-based writer and poet Jenny Zhang’s short-story collection Sour Heart alternates between sweet and rancid, light and gritty, juvenile petulance and innocent grace – all within each story.

She also blurs the lines between fiction and autobiography: every story features a young girl who has moved from China (usually Shanghai) to New York with parents who struggle to make ends meet in Brooklyn’s cheapest neighbourhoods and struggle even more to give her the attention she craves in the rare moments they are together.

Zhang claims to have worked hard to ensure her stories are sufficiently fictionalised to not infringe on the lives of her family. Each is written in the first-person and they all have recurring narrative strategies, so plots and characters blend together – which is unfortunate, as Zhang has a bold voice.

She captures the cruelties, longings and absurdities of childhood and adolescence so well that readers may feel like they’re eavesdropping on the most intimate moments of the characters. Zhang repeatedly features juvenile sexuality and juvenile cruelty: of course, for children discovering sex and the power of sex in their immature way, the two are closely linked.

Later, however, the story descends, or devolves, into the two girls and a friend probably sexually assaulting (the lines are blurred) Lucy’s boyfriend, Jason. (Lucy had chosen him because “he was the second shortest boy I knew”; his nickname is Shrimpson.) It’s dispiriting stuff. And yet the voice is always true, and we feel not so much outrage as sadness and disgust at their ignorance and abuse. Zhang packs a complex bucket of emotions into that story, and one can understand the revulsion some reviewers have felt, but it’s a brave attempt to bring a hidden dynamic to light.

Throughout Sour Heart, the characters are damaged and filled with febrile discontent.

The opening story, we later come to understand, is almost an overture. Christina and her parents live a life of shatteringly precarious poverty, and flop around dreadful, overcrowded studio apartments in the meaner parts of Brooklyn. The tale is full of acute observations of the degradations of poverty. In Washington Heights, Christina and her parents sleep in a “cramped room with five mattresses pushed up against each other”. Her skin itches from the bedbugs, “like there were little tiny ants carrying sticks of fire and doing somersaults and cartwheels all over my body” and she whines and scratches constantly.

In passing, she lists the other occupants of the room: other fresh-off-the-boat Chinese couples struggling to adapt to America, despite their education and former social positions. Later on, the new narrator of each story reveals one of the couples to be her parents. (Usually they’re complaining about when they first arrived in New York and had to share a room with a girl who wouldn’t stop complaining about itching.) This helps tie the stories together but, because the tales are already so similar, it is slightly too clever an approach.

The damage comes from two sources: poverty and the older Chinese generation. Stacy’s grandmother is so desperate for love and attention that she encourages first Stacy and then her brother to be co-dependent on her while dismissing the needs of her husband, who is fighting cancer back in China. Annie’s mother in “Our Mother Before Them” is a narcissist, but you feel a pang of empathy as she passes the pain and poverty she has been through to her children.

Violence seethes throughout, as in “My Days and Nights of Terror”, whose narrator only dimly perceives the aggression between her parents until it bubbles up ferociously at the end, and then she comes under the reign of terror of a horrifying school bully.

As is often the case where voice predominates, content takes precedence over form. There’s an artless shapelessness to the stories. Themes and motifs recur, not so much to convey greater meaning as to provide hooks for the reader.

The tone is almost always raw, sardonic and crude. The mostly plotless stories make ending them difficult: how to bring about a conclusion or catharsis when there’s no typical narrative? Several times Zhang ends on a dream, or a dreamlike image. This can be effective, as in “The Empty the Empty the Empty”, where you feel Lucy recoiling from the sexual cruelty inflicted on Jason. Sometimes it feels a little baffling, as when Annie is lifted up by her uncle during her birthday, “and I locked my legs together and held my arms out as if I were a plane and the red and blue and purple and green and silver balloons I pushed out of my way were the clouds parting for me as I made my ascent into the unknown territory of the skies”.

While not all the stories work, Sour Heart is a boldly original and confident fictional debut, capturing the Chinese-in-New York experience: the start at the bottom, the penny-pinching, the striving, the fear of other races, the parental demands for educational excellence, the squalid housing.

Zhang has a great ear for speech, especially childish back-and-forths and lazy articulations: “Un-un-uh” is perfect as a short cut for “I dunno”. She breaks taboos and captures the seething frustrations of a section of society haunted by the past and struggling now so as to not be downtrodden later. Her evocation of girlhood is audacious, even groundbreaking: few have gone where she has in portraying nascent feminine sexuality.

Ultimately, the stories could do with bolder lines and cleaner shapes. They feel arty, but they lack a little artistry.