The Stolen Bicycle: Wu Ming-yi expertly weaves a narrative of Taiwan

Wu’s fifth novel blurs the lines between memoir and fiction, riding a singular obsession deep into cultural history

The Stolen Bicycle

by Wu Ming-yi

Text Publishing

Wu Ming-yi’s profoundly moving fifth novel uses an obsession with antique bicycles to journey deep into Taiwan’s 20th-century history.

The book by the Taiwanese author, literature professor, butterfly scholar, artist and environmental activist is only the second of his acclaimed works to be translated into English, and won rave reviews in Taiwan – and the Taiwan Literary Award – following its Chinese-language release in 2016.

The Stolen Bicycle, which also features Wu’s intricate illustrations, highlights why this 46-year-old author is widely considered the most influential writer of his generation in Taiwan. It’s a novel that confounds conventional expectations of narrative pace and form, even as it burrows deep into the reader’s conscience. It is a vast, unruly coil of disparate narratives wrapped inside the story of a novelist and self-described “bicycle fanatic” named Ch’eng, who declares early in the book that “this story has to start with bicycles. To be more precise it has to start with stolen bicycles.”

This is how Wu starts entwining the threads of Taiwan’s tangled history with that of the bicycle and his family before weaving them into a fictional fabric all of his own. His keen sense of Taiwan’s “linguistic polyphony” is as potent a motif as the history and lore of the iron horse.

His narrator’s family obsession with stolen bicycles was seeded during the Japanese era in Taiwan, a time “when a bicycle was like a Mercedes-Benz today”. To be precise, that obsession began in 1905, the year in which his illiterate, maternal great-grandfather gave a newborn son, Ch’eng’s father, a newspaper article about a stolen bicycle.

Ch’eng’s own obsession with the iron horse grows from a reader’s response to one of his novels. He wrote a book based on the story of his father, who, like thousands of young Taiwanese men during the war, had helped build fighter planes in Japan, before plying his trade as a master tailor in Taipei’s Chung Hwa market. Twenty years before the novel was written, his father disappeared. As did his father’s bicycle.

Soon after the novel’s publication, Ch’eng receives an email asking about fate of his father’s bicycle and the author is gripped by a desire to track it down. His quest to find a brand of bike no longer manufactured in Taiwan, a Lucky, leads him not only to a group of enthusiasts, who “like members of some secret underground organisation are brought together by their strange obsession with Lucky bicycles”, but to places that no longer exist. Places such as Chung Hwa market, which was demolished in 1992 yet remains vivid in people’s memories.

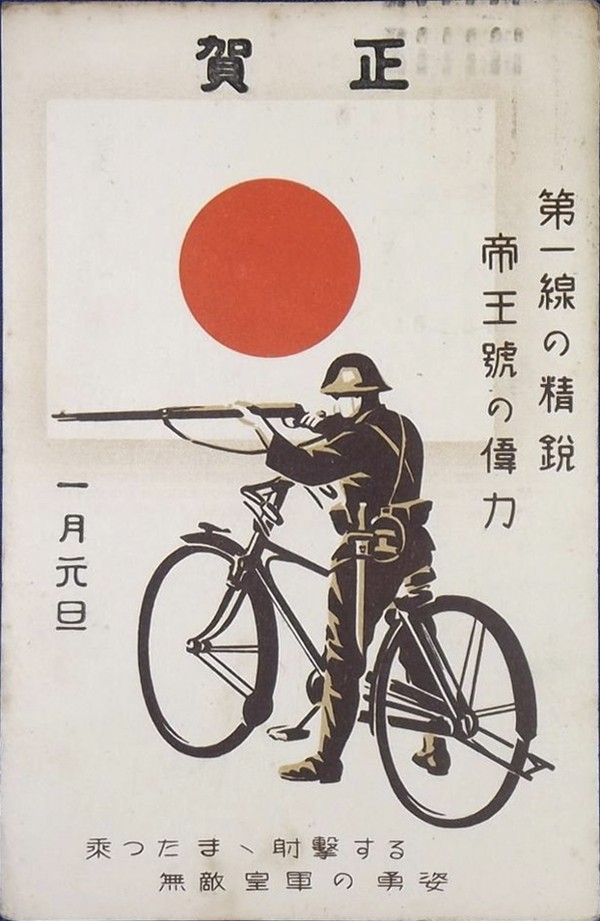

With Abbas, whose own family story is intermittently threaded through the narrative, we venture out on a circuitous bicycle journey to the jungles of Burma, Thailand and Malaysia, on the trail of those who endured, suffered or died fighting on different sides during the second world war. Abbas’ father, a member of Taiwan’s indigenous Tsou tribe, had been in the Japanese Army’s Silverwheel Bicycle Squad, and Abbas borrows Old Tsou’s ancient Hinomaru to cycle jungle battlefields.

The agility of Japan’s Silverwheel troops, who attacked retreating British Indian troops during the Malaya campaign, along with a detailed account of all wartime bicycles, is featured in one of a series of excerpts from an archive on bicycle construction, design philosophy, development and maintenance that is spliced between the chapters. Titled simply “bike notes”, these also divulge titbits on a dizzying array of subjects, including a brief history of Western medicine in Taiwan, the development and significance of the Shisheido cosmetic company and the evolution of photography in Japan.

As an adult, the emails reveal, A-hun mastered the art of making butterfly collages that were so sought after during the 1960s and 70s that “the butterflies themselves, once ubiquitous in the hills and fields, gradually took their leave of the era and the wild, never to return again”.

It is only in the final chapters that the enigmatic threads of this novel come together, like pieces of an unfamiliar jigsaw, and the power and scope of this extraordinary work hit home. For, like A-hun, and the thousands like her who painstakingly deployed layer upon layer of butterfly wings to fashion luminous collages, Wu uses layer upon layer of quotidian detail, historical fact and human memory to fashion a vast vision of the history of not just Taiwan, but of the entire era.

A rare accounting of the costs of war and post-war industrialisation on both humans and the natural world, The Stolen Bicycle is a haunting homage to what its author calls, “the unrepeatability of life”.