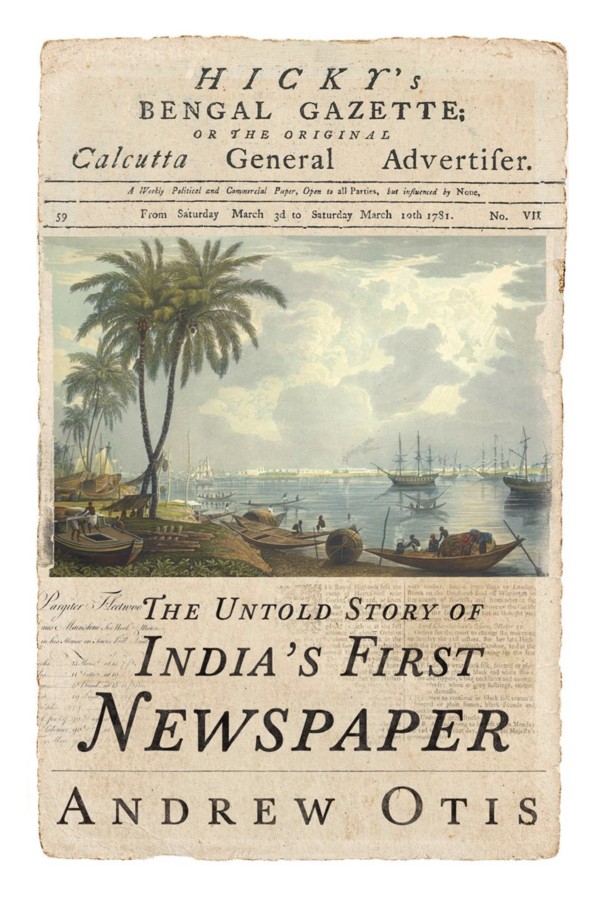

An Irishman in colonial India’s ill-fated enterprise: the rise and fall of Asia’s first newspaper, as told in new book

Andrew Otis’s non-fiction debut chronicles the short lifespan of Hicky’s Bengal Gazette, a provocative English language weekly that played a role in bringing the East India Company under the control of the British government

Hicky’s Bengal Gazette

by Andrew Otis

Westland

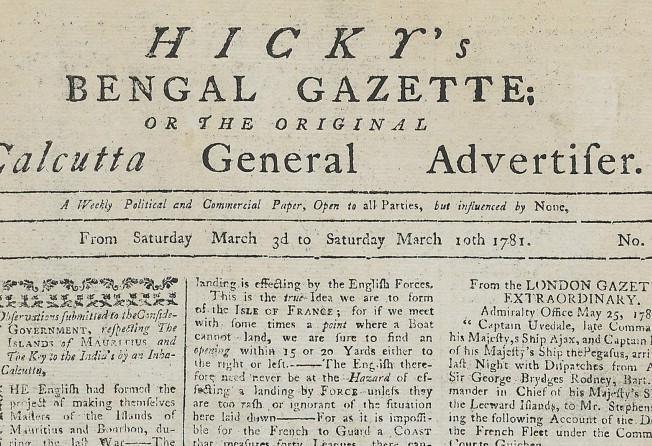

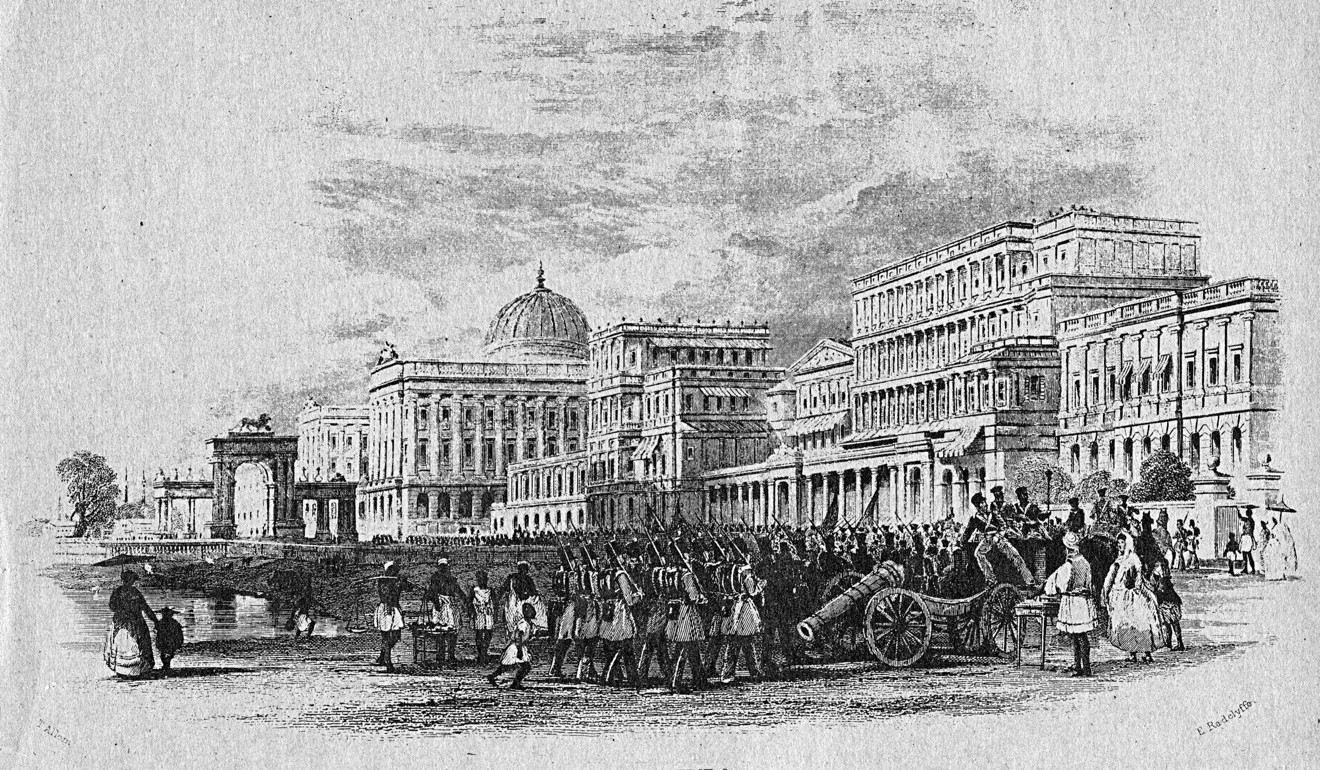

Hicky’s Bengal Gazette meticulously chronicles the swift rise and precipitous decline of the first newspaper to be printed in Asia. James Augustus Hicky, a temerarious Irishman looking to make his fortune in India, began printing the Bengal Gazette in Calcutta (now Kolkata) on January 29, 1780. But just over a year later, he was charged with three counts of libel against Warren Hastings, the governor-general of India and the most powerful Englishman in the country, leading to legal dramas that finally closed the paper on March 23, 1782.

At a time when massive fortunes could be amassed through obedience to the East India Company, Hicky’s decidedly undiplomatic mission of exposing the corruption and imperialist obsessions that underlined the company’s agenda was subversive.

Hicky’s Bengal Gazette – the non-fiction debut by scholar Andrew Otis – is weighty material, given that various facets of colonial history are inextricable from each other. However, Otis’ book is not weighed down by its narrative and moves with the ease of fiction.

Some readers may take issue with the focus on a group of historical figures and wish for some authorial meandering (which can be pleasurable in books about history) but Hicky’s Bengal Gazette remains a compelling read all the way through to its elegiac conclusion.

The book opens with the death of Hicky on a ship sailing to Canton (Guangzhou), after which it traces his arrival in Calcutta and lays out the state of affairs in a country increasingly encumbered with warfare and occupation by the East India Company.

Hicky’s relationship with the company was initially amenable. As one of few printers in Calcutta, he was approached to print new standardised regulations intended to curb corruption in the army. However, when the company’s red tape left him in the lurch, he set his sights on the news business.

When Hicky launched the Bengal Gazette, Europeans on the subcontinent received their international news from newspapers delivered by ship several months after they were published. At a time of ubiquitous British warfare, newspapers were vital for deciding trade routes and learning of casualties in battles. Hicky’s newspaper was, unsurprisingly, aimed squarely at the British, having arrived more than half a century before the English Education Act of 1835 would spread the English language among the Indian masses.

Hicky initially tried to avoid controversy, promising not to publish anything that could “convey the smallest offence to any single individual”. The Bengal Gazette was a community bulletin board and featured innocuous calls for better roads and infrastructure. As its subscriber base widened and it began influencing bureaucratic decisions, Hicky became more brazen and his vendetta against the company’s moral failings more intense.

For Hicky, the paper was both a public duty and a vehicle with which to exact vengeance on the people who had stood in his way. One of these was clergyman Johann Zacharias Kiernander, who refused to take on Hicky’s printing services and whose almanacs Hicky had plagiarised a few years earlier. Publishing an anonymous account from an associate, Hicky accused the clergyman of embezzling funds meant for orphans, which led to Kiernander filing two libel cases.

The bulk of Hicky’s ire, however, was reserved for the company and its imperialist crusade. For example, he took issues with a Calcutta by-law that imposed taxes on people without representation. The newspaper also criticised the army’s promotion system and spoke of soldiers’ miserable conditions while their superiors lived in luxury. Also targeted by Hicky was the Sadr Diwani Adalat, a court system that rendered the Supreme Court obsolete and allowed Hastings to tighten his grip on the justice system.

The Bengal Gazette devoted much space to Indians, particularly those who were marginalised and destitute. While Hicky does not seem to have counted on Indians’ facility for reason and enlightenment, his sympathy for them still stood in contrast to the attitudes of most of his peers.

The paper went from supporting British conquests to extolling the virtues of American revolutionaries. Hicky called on the Indian public to revolt and stopped just short of encouraging the army to carry out a coup against Hastings. After the company’s takeover of Benares (modern-day Varanasi), Hicky’s correspondents supported the rebellion by Raja Chait Singh. Following the Battle of Pollilur, which led to the Bengal Gazette accusing the company army of fighting a pointless war, Hicky praised Hyder Ali, the sultan of Mysore, for escorting company troops to captured territory.

Of course, it was not long before Hicky had made powerful enemies. October 1780 saw the founding of the pro-establishment India Gazette, which was steeped in British supremacy and, unlike Hicky’s paper, received free postage (and patronage) from the company. After Hicky criticised Simeon Droz, chief of the board of trade, Hastings prohibited the newspaper from being mailed through the post office. Hicky’s biggest setback, however, and the beginning of years of legal troubles, was the five libel charges brought against him by Hastings and Kiernander.

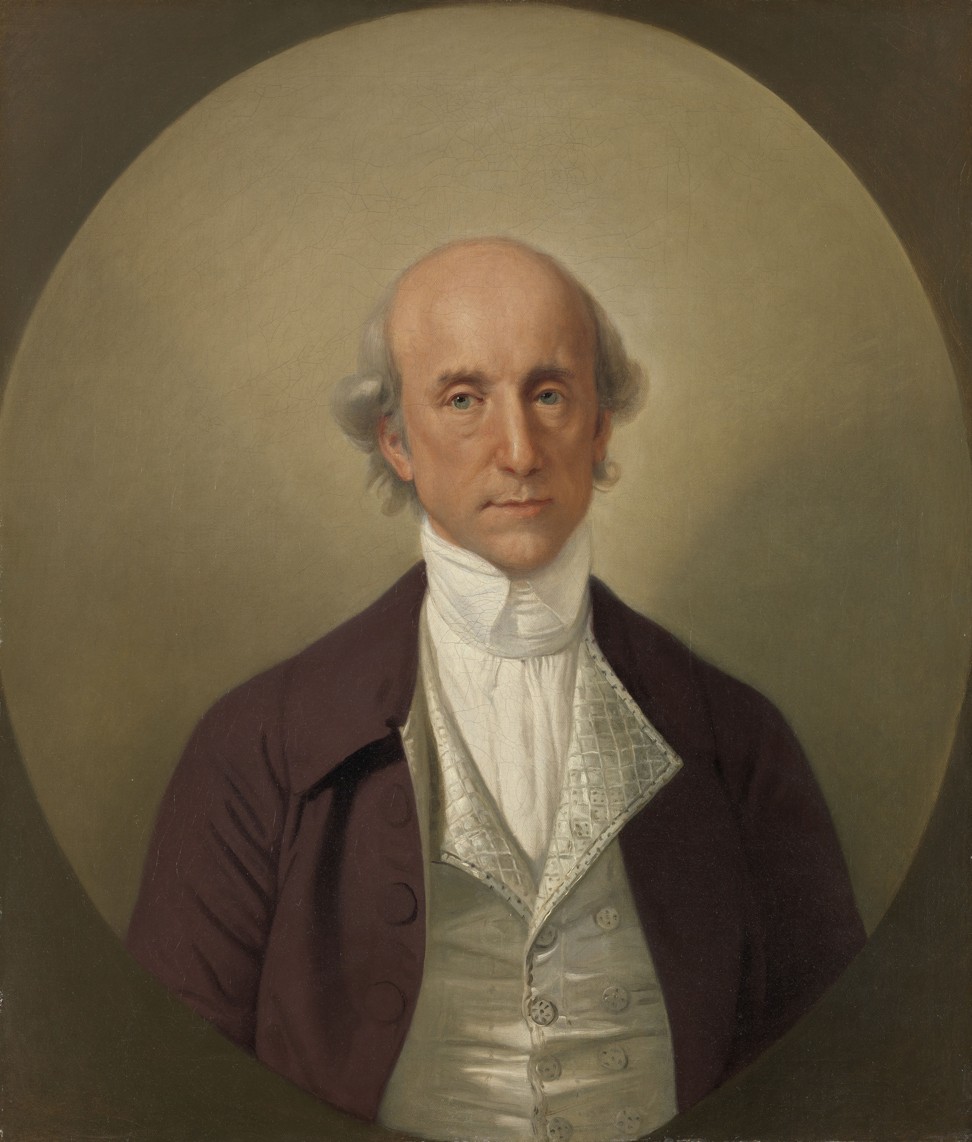

Otis pleasingly complicates some of the characterisations. In his early days, Hastings had noble intentions in India, even declaring that “if our people instead of erecting themselves into lords and oppressors of the country, confine themselves to an honest and fair trade, they will be everywhere courted and respected”. He even leaves India disillusioned with violence and crony politics.

But after his return to India in 1769, precipitated by a decline in his family fortune, colonial power seems to have taken a firm grip on Hastings. Conquests are incessant, Indians are taxed more than ever, even at the height of the Bengal famine, and slavery is encouraged. During this period, Hastings wrote: “I shall have no competitor to oppose my designs, to encourage disobedience to my authority […] to excite and foment popular odium against me. In a word, I have power, and I will employ it.”

Otis also does not whitewash the coarseness of the Bengal Gazette. Hicky published faux theatrical notices that cast various company men as villains. In one, Hastings is both a Mughal emperor and a misguided Don Quixote. Hicky relied too on bawdy provocations, making fun of a colonel’s libido and writing that war had affected Hastings’ perineal spring (a dig at erectile dysfunction). He noted that Edward Tiretta, the head of public works, “had a happy Turn for EXCAVATIONS and Diving into the Bottom of things”, a possible reference to his sexual orientation.

During one outrageously funny outburst in court, Hicky tells the chief justice, with whom he had a chequered history, that a juror was “tolerably familiar” with the chief justice’s wife. And one lawyer notes in his memoir that Hicky “was extremely violent, yielding so much to sudden gusts of passion and so grossly abusing whoever acted for him that at length not a professional man could be found”.

So it is to Otis’ credit that Hicky comes off as a nuanced character and not a figure of derision. But the author is not always able to convert these public figures into fully fleshed-out characters with private lives. The absence of Hicky’s 12-member family is understandable but conspicuous. Otis also fails to mine how social class and Hicky’s Irish identity separated him from the men in the company’s upper echelons as well as Philip Francis, a political rival of Hastings who was instrumental in the downfall of the governor-general.

Hicky’s work played a significant role in the passing of the East India Company Act of 1784, which brought India under the control of the British Empire

And Hicky’s Bengal Gazette occasionally feels musty. Otis has a fondness for closing chapters with melodramatic denouements (“His name was James Augustus Hicky”). Still, he makes this key piece of colonial history and Indian journalism both vibrant and droll, which is no small task. There’s even something poignant about the synchronicity between Hicky, Hastings and Kiernander’s fading fortunes in the closing chapters.

The book raises knottier questions too. Hicky’s work played a significant role in the passing of the East India Company Act of 1784, which brought India under the control of the British Empire. Was the Bengal Gazette simply a Machiavellian power struggle between members of the English gentry, namely Hastings and Francis, vying for influence both in Britain and abroad? Was the newspaper anti-establishment or anti-company? After all, colonial power simply realigned under the nefarious fist of the crown. There are no easy answers.

Hicky remains largely unknown in the Indian popular imagination. Most history textbooks cite social reformer Raja Ram Mohan Roy as the father of Indian journalism. So Hicky’s Bengal Gazette is both a solid primer on the inauspicious beginnings of journalism in India and a cautionary tale about where it can lead.