Chinese science-fiction author Liu Cixin’s Ball Lightning rewards readers patient enough to navigate the techspeak

Flawed prelude to The Three-Body Problem, the sci-fi maestro’s major hit, asks the big questions but labours over small details

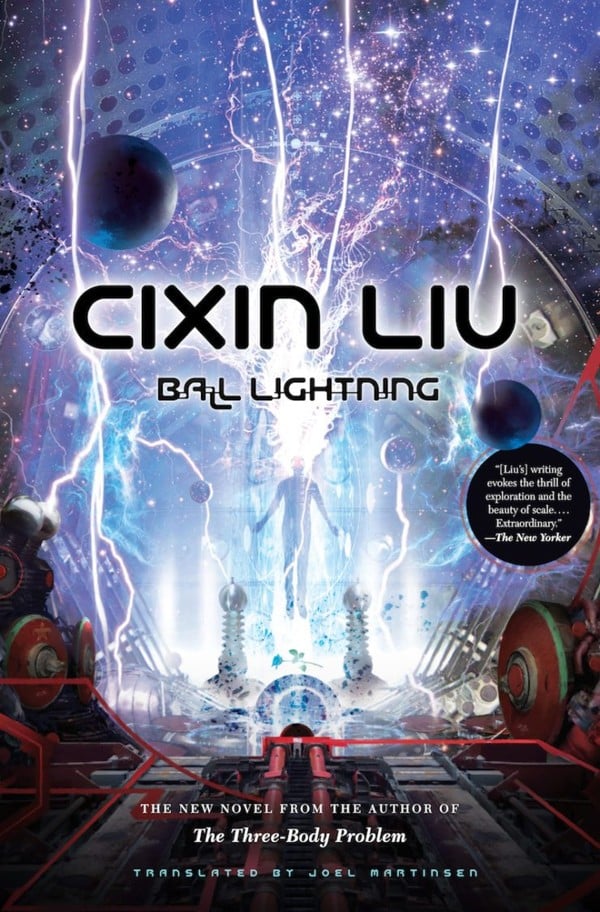

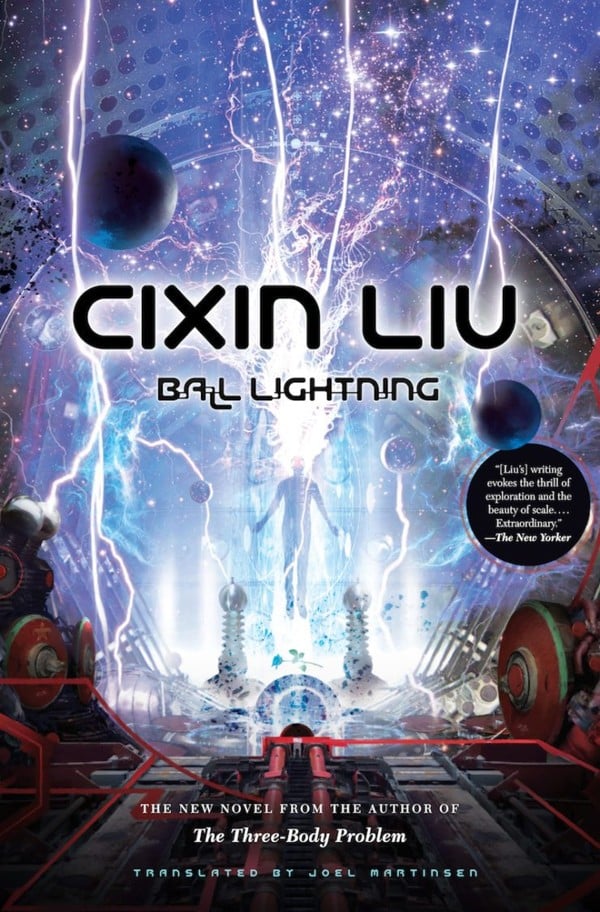

Ball Lightning

by Liu Cixin (translated by Joel Martinsen)

Tor Books

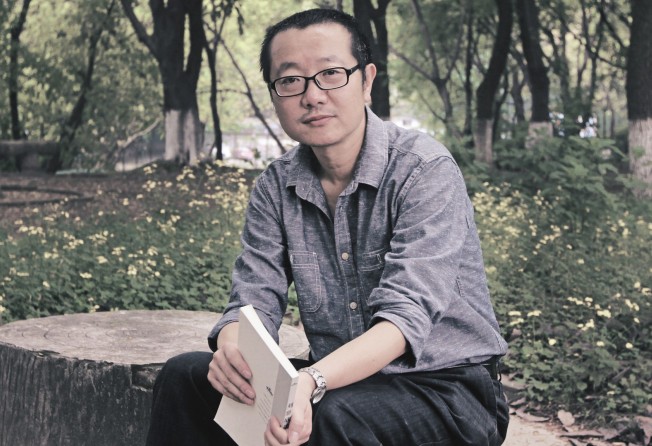

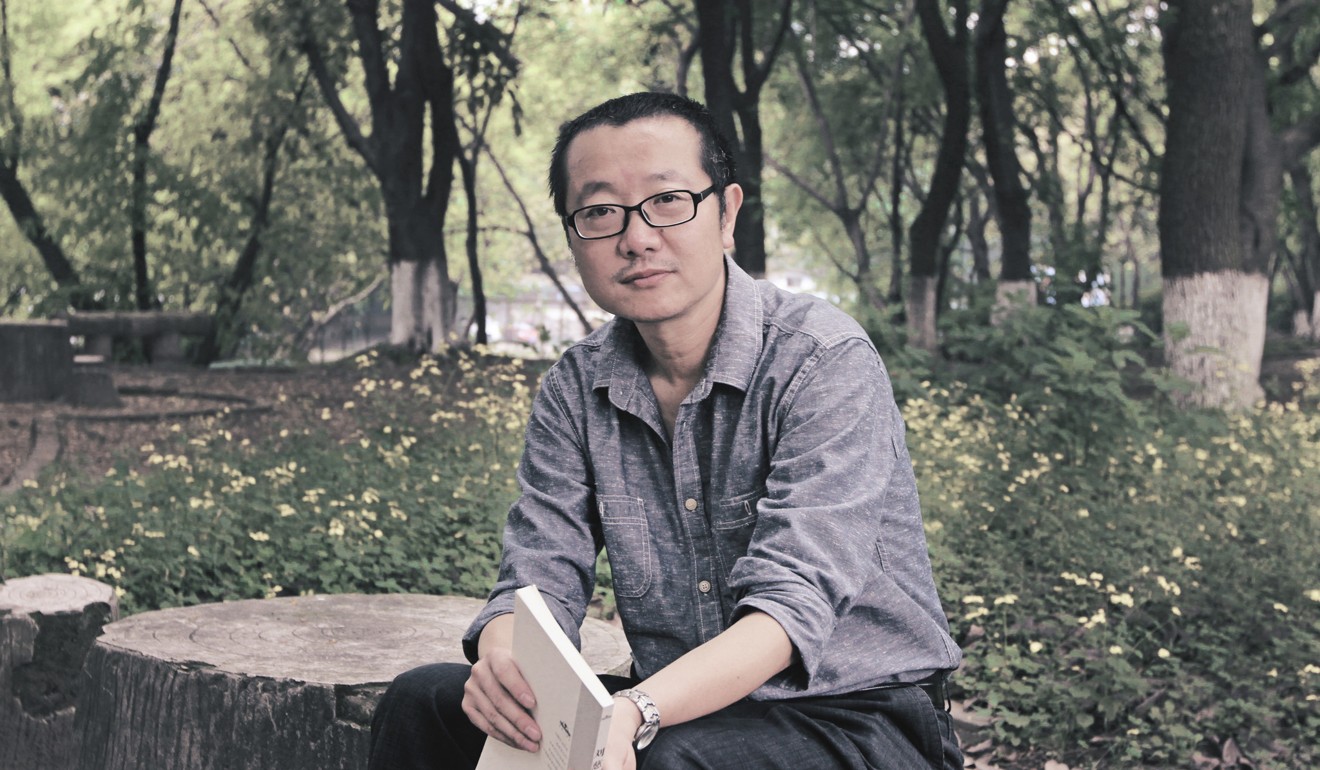

Leading Chinese science-fiction author Liu Cixin wrote Ball Lightning in 2003, when he was also completing his award-winning trilogy The Three-Body Problem . Fifteen years (and one international smash hit) later, it is flashing out of China and across the world thanks to Joel Martinsen’s English translation.

This is ball lightning – a real, but extremely rare natural phenomenon. What made this event life-changing for Liu was its proximity to another exceptional experience: “That same year, I read two books by the British writer Arthur C. Clarke, 2001 and Rendezvous with Rama.” This pair would directly inspire The Three-Body Problem. But Ball Lightning, by contrast, emerges from a different tradition: the Chinese “invention story”.

Unlike the Promethean dystopias favoured by Western novelists, which linger on the detrimental effects of scientific innovation (see Frankenstein, for example), Chinese writers are “preoccupied with the description of a futuristic technological device and speculation on its immediate positive effects”, Liu writes.

This just about describes Ball Lightning, which opens on a note of raw emotion. Fourteen-year-old Chen is celebrating his birthday with his parents. Outside thunder rumbles and lightning flashes: “On a stormy night, you get a sense of how precarious family life really is,” Chen thinks, with what proves to be double prophecy. Suddenly, one arc pierces the wall forming a basketball of hazy red energy that, after hovering around the terrified trio, incinerates Chen’s mother and father.

The consequences for the boy are profound and diverse. Grief leaves him isolated, emotionally stunted and obsessed with ball lightning. Enter the first of the novel’s themes: “The key to a wonderful life is a fascination with something,” Chen’s father counselled his son just before dying. In Ball Lightning, healthy fascination wrestles constantly with morbid obsession. Chen embodies this fight as he tries to understand his parents’ death through relentless study at university.

His first mentor, Zhang Bin, serves a Promethean caution. Zhang, like his student, is brilliant, solitary and damaged: his even-smarter wife, Zheng Min, was herself killed by ball lightning while conducting fieldwork into the subject. Having described her death to Chen, Zhang adds: “I think you’ll understand that for people like us whose mind and body are occupied so completely that the obsession becomes a part of you, anything else in life will always come second.”

Chen meets Zheng Min’s modern incarnation in Lin Yun, who develops “new-concept” weapons for the army: for instance, “attaching tiny sacks of corrosive fluid to cockroaches […] so they can destroy the circuits of the enemy’s weapons systems”. Lin’s violent ambitions for ball lightning are single-minded enough to qualify as addiction. Her ability, or rather inability, to weigh the moral consequences of her research will direct the plot as a whole.

After a brief moment of attraction, Chen and Lin get on with the serious business of bottling ball lightning, which hovers tantalisingly in a netherworld between abstract theory and practical reality, between imagination and materiality. “This is a dream,” Chen screamed as his parents were killed. “Don’t waste your [life] on an illusion,” he is warned by another fanatic. Any nagging similarity to Liu’s fiction is made explicit: “If you could really generate that kind of artificial lightning,” Lin shouts at one point, “[it] can be as accurate as a page in a book.”

The character charged (pun unintended) with transferring Chen and Lin’s ambitions into the tangible world is Ding Yi, whom Liu fans will recognise from The Three-Body Problem. Here he comes across as a somewhat hackneyed slacker genius, working on the margins of the mainstream, sabotaging a sure-fire Nobel Prize, and wearing vests and shorts. Thinking outside the storm cloud, he makes Lin’s hopes for ball lightning a terrifying reality.

The novel’s allegiance to hard science fiction means there is plenty of technical exposition, which you will either find profoundly intriguing or as dull and opaque as ditch water. I am not especially proud of my resistance to these sections, which are certainly hard and doubtless scientific. Nevertheless, my eye did glaze over reading sentences such as, “In other words, when the chips experience matter-wave resonance with the macro-electron, they turn into a macro-particle in a quantum state. Ball lightning’s energy release is essentially the full or partial superposition of the probability clouds of it and its target.” In other words? Essentially? We need another Joel Martinsen to translate this English into, well, English.

The upside of all this superpositioning emerges when Ding’s symposium finally stops and the plot starts again. The means is an eerily credible takeover of a nuclear reactor by a terrorist group called, a little obviously, The Garden of Eden. The mastermind is a ruthless luddite disguised as a middle-aged teacher, whose manifesto turns the novel’s overt credo on its head: “Life has been raped by technology, and we’re going to make it pure again. Have you ever seen an atom? How do they have anything to do with us? Don’t let those scientists trick you.”

The teacher shows she is deadly serious when she murders a child in her care because he wanted to be a scientist: “His little brain was already polluted by science. Yes, science pollutes everything!” Perhaps she had been driven to madness by those earlier sections. The stakes are raised higher still when Lin suggests they take out the terrorist with ball lightning. The grotesque dilemma is that such an action will kill a number of the children, too.

This brief but exciting interlude is so refreshing that I felt a dilemma of my own. The teacher-terrorist may be obscene, but I found myself warming to her technophobia. Lin’s high-concept weapon may save thousands, and even millions of lives, but was it worth the tedium of the writing?

My sympathy for the luddites only increased as Liu returned to his physics tutorial. No wonder Chen quickly becomes depressed and removes himself from Ding and Lin’s presence. These longueurs are themselves rescued by a second emotional climax when Ding tracks Chen down and explains the melancholy background behind Lin’s obsession with new-concept weapons: namely, the death of her mother.

Ball Lightning is not Liu’s best work, but it provides a fascinating version of an enduring debate: does science’s capacity to do evil as well as good make it morally neutral?

In doing so, the novel circles back to its own tender beginnings: “On a stormy night, you get a sense of how precarious family life really is.” For all the grandstanding between scientists and military commanders, Ball Lightning is essentially a story about family. What makes the endless jargon ultimately bearable is the impression that it helped Chen, Lin and Zhang endure, if not overcome searing loss.

Ball Lightning is not Liu’s best work, but it provides a fascinating version of an enduring debate: does science’s capacity to do evil as well as good make it morally neutral? “The scalpel can kill too,” Chen is reminded. The narrative explores this theme more expansively than Liu’s afterword suggests. The problem is the vim of the narration, which moves, like a storm perhaps, in fits and starts, with exposition thundering over flashpoints of more effective drama. Luckily the strength of the fits (the opening, the confrontation at the reactor, Lin’s ultimate confession) just about survives the boredom of the rest.

Liu’s own warning about the absence of political, economic and cultural contexts is also close to the mark. This wasn’t as damaging as he suggested, at least in my reading. One of the novel’s more intriguing devices was to relegate an ongoing international war between China and the United States to a tiny subplot in Chen’s narration. This decision didn’t expose the limits of old-school Chinese science fiction so much as reveal the depths of Chen’s obsession: even a third world war can’t break his fixation with ball lightning.

There were moments when I wondered whether the concluding portrait of China reduced to a primitive, agrarian society nodded towards Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward. And was the preoccupation with all-seeing observers an attempt by Liu to critique an authoritarian state?

But the novel only flirts with dystopia; Liu’s vision in Ball Lightning is ultimately, if cautiously, optimistic. Denuded of technology after ball lightning wipes out China’s computers, his characters form old-fangled relationships with other humans. That’s not to say that darker clouds are not lurking on the horizon. The final hints of enemies in deep space knowingly anticipates the darker mood of The Three-Body Problem.

Readable and intelligent, Ball Lightning is a flawed prelude to a modern classic.