Empire of the Winds: account of Southeast Asia’s ‘great archipelago’ rejects China’s take on its history

- Author Philip Bowring explores the significance of a region he calls Nusantaria stretching from Malaysia, Taiwan and the Philippines to Indonesia and Timor

- Trade winds, resources and wealth made the more than 20,000 islands of the archipelago into a hub of global trade, he writes

Empire of the Winds: The Global Role of Asia’s Great Archipelago by Philip Bowring, published by I.B. Tauris

“Trade and tolerance are happy bedfellows. So too are freedom of navigation and the absence of monopoly,” Philip Bowring writes. It becomes a recurring theme in his riveting history of … of what?

Bowring has taken on the mission of restoring to its rightful place in world history a region that shaped global trade, and with its unrivalled shipbuilding techniques and navigation skills drew disparate cultures – and their ideas and know-how – together across vast oceans, and whose contribution to humankind’s dominion over this planet’s resources has been largely forgotten.

This is a region without a name. Bowring makes one up: Nusantaria. The word “nusantara” exists in Malay but has come to mean “archipelago”, and specifically Indonesia. Bowring’s typographical tweak aims to construct a sweeping cultural tradition that stretches from Sumatra and peninsular Malaysia, through the Philippines and Taiwan and across to Timor, the Maluku Islands and still farther east.

The book’s title refers to the region’s strategic and serendipitous location at the confluence of seasonal winds. Being able to sail in predictable directions at certain times of the year was a major encouragement to take to the seas. Other inducements included the uneven distribution of resources and wealth across the more than 20,000 islands that form Asia’s Great Archipelago – making a necessity of short hops to neighbouring islands to exchange basic commodities. Over centuries, maritime skills were honed as traders made ever longer and more ambitious voyages.

Though key commodities varied over time and from place to place, the region was the “origin, market or transit choke point” for more than 2,000 years of long-distance commerce.

Consider the humble clove. The Romans bought them, probably via India, while first-century Indo-Roman pottery found its way to Bali. A millennium and a half later, the price of cloves in Malacca was 10 times higher than in their native Maluku Islands. And that price had jumped sixfold by the time the spices reached India, and a further tenfold in Europe. Little wonder Portuguese invaders preferred trade to plunder after they seized Malacca, the then-dominant Nusantarian port state on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula, in 1511.

Little wonder too that Nusantarian elites preferred to live as the maritime equivalent of rentier landlords rather than suffer the hardships and reverses of long-distance commerce. According to one Chinese account of the Champa kingdom in what is now Vietnam: “When trading ships arrived, their cargo was recorded by officials in a leather book and two-fifths of the cargo was held as duty.”

Governments that could provide security, good governance and predictable rules of trade and commerce were of great attraction to merchants faced with the risks of foul weather, piracy, being preyed upon by less scrupulous states – or massacred by hostile natives, as happened on at least three occasions in southern China.

This allowed such havens to earn a rich living extracting tolls on trade passing through their ports. Indeed, the “happy bedfellows” of trade and tolerance have proved much more enduring than any of the “Empire” of Nusantaria.

Bowring, in a remarkable display of taut writing, whisks us through the archipelago’s geological eruption and mythic floods to the rise and fall of multiple port states and emerging regional dynasties and into the modern era of disruption, decay and dismemberment in less than 300 pages. At the same time, he does a wonderful demolition job on Beijing’s self-serving take on Asian history.

With China then, as so often now, preoccupied with internal problems or focused on threats from the north, Nusantaria fell under the sway of more expansive and expressive Indian and Arabian thought and cultural influence. Readers of Bill Hayton’s The South China Sea (2014) or John Keay’s India (1999) will welcome Bowring’s addition to their narrative of Asian societies bound together in shifting circles of power, rather than the anachronistic retelling based on the modern nation state – a version that has handed to Beijing an outsized claim to regional leadership and a territorial ambition to match.

In fact, claims that pottery shards and Chinese graves on atolls prove the Middle Kingdom has rights to almost all of the South China Sea show little more than that ceramics don’t rot, that trade through Nusantaria and beyond was flourishing and multicultural, and that many Chinese have for centuries fled oppression and poor conditions in their homeland in search of a better life.

Bowring writes that the region’s port states were lifted by the rising tide of global trade thanks to a combination of openness and tolerance. Chinese dynasties often neglected to enforce their rights to China’s littoral coast and neighbouring polities. That left the door to the boat shed wide open for not only European incursions, but also entrepôts and trading hubs strategically placed at key points in the trade winds.

European nations, in particular, used proxies to extend their rivalries. English free-trade merchants actively undermined Dutch attempts to impose a regional monopoly on trade but also happily sold arms to competing sultans, stoking regional conflicts and eroding the military advantage of the Dutch East India Company.

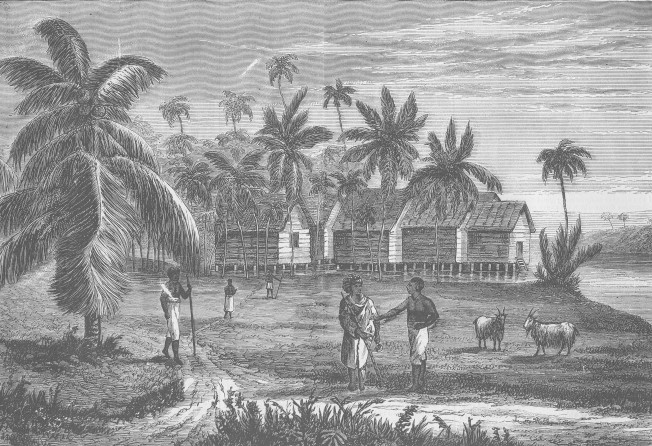

As commerce became more international and lucrative, the weaknesses of Nusantaria’s small and competing states saw them increasingly relinquish their share of maritime trade. Chinese ships accounted for about half of all vessels calling at Batavia, capital of the Dutch East Indies, from regional ports by the 18th century. Local political elites focused on consolidating their land holdings – which they rented out to European and Chinese plantation operators, using the revenue to fund luxurious lifestyles and their internecine conflicts.

In what would become a familiar and tragic motif over coming centuries, the growing exclusion of local populations from the fruits of either trade or plantations fuelled tensions with the thousands of poor labourers who had escaped miserable lives in China. Competition from Caribbean sugar plantations lowered wages across Southeast Asia, ethnic tensions soared and thousands of Chinese were massacred in Batavia in 1740.

Taiwan’s role in the Nusantarian orbit provides an illuminating side story. Relatively isolated and of little strategic significance on the main trade routes, Taiwan was left largely untroubled until the island became a consolation prize in the Dutch-Portuguese-Spanish tug of war for ascendancy in Asia. After the Dutch booted Spain out of the island in 1642, they found the proudly independent indigenous people of Taiwan unwilling to take up hard labour on European plantations. And so the Dutch began to encourage Chinese immigration. Within six years, 15 per cent of the population of lowland areas of Taiwan was reported to be Chinese, and little more than a decade later, the Dutch were evicted by an army led by Zheng Chenggong (better known as Koxinga), the son of a Fujian pirate leader and a Japanese mother.

Bowring’s abbreviated account inevitably thins in parts – the pace picks up as we enter the colonial era until it feels like watching history through the window of a Chinese bullet train

Descriptions from the early years of Spanish dominion portrayed a society of highly developed skills in varied areas including mining, metalwork and rice cultivation. Gold decorations and jewellery were widely worn. “The chief women also wear beautiful shoes, many of them having shoes of velvet adorned with gold,” wrote Antonio De Morga, a senior Spanish official, in 1609.

Contemporary accounts also describe societies that were tolerant and in which women appear to have enjoyed a social status that would be eroded by the encroaching puritanical blankets of Christianity, Islam and – Bowring says – Confucianism. One manifestation of female emancipation was in the practise of inserting metal objects under the skin of the man’s penis to increase the sexual pleasure of women.

Bowring’s abbreviated account inevitably thins in parts – the pace picks up as we enter the colonial era until it feels like watching history through the window of a Chinese bullet train. This is understandable as the book seeks to fill a substantial gap in awareness of the linguistic, cultural and historical ties that have long been submerged and written over.