In Ways of Heaven, Roel Sterckx unpacks ‘Chinese thought’ for the Western reader

- The Joseph Needham Professor of Chinese History, Science and Civilisation at the University of Cambridge offers insight into the Chinese psyche

- Philosophy in the Chinese sense rarely indulged in debate for its own sake, instead dealing with the practical

Ways of Heaven – An Introduction to Chinese Thought

by Roel Sterckx

Basic Books (Hachette),

4/5 stars

“The knowledge that the average Chinese teenager or college student knows far more about ‘us’ than ‘we’ know about ‘them’ should be a gentle wake-up call,” writes Roel Sterckx. “To understand China, we need to learn to think Chinese.”

With Ways of Heaven – An Introduction to Chinese Thought, the Joseph Needham Professor of Chinese History, Science and Civilisation at the University of Cambridge has produced an approachable account of Chinese thinkers that is as crisp, clear and readable as the sometimes slippery nature of those ideas permits.

If your perception of Chinese philosophy goes no further than Kung Fu Panda’s “One often meets his destiny on the road he takes to avoid it,” note that this idea was not only familiar to the authors of Greek tragedy but was expressed in that particular form by the French fabulist Jean de la Fontaine. You need to rethink.

Chinese philosophers have had some influence in the West – Voltaire and Leibniz were seduced by the mistaken idea of a society functioning perfectly on the basis of moral reasoning without a supervising God. But Chinese thinkers fail to appear on the syllabuses of university philosophy courses in the English-speaking world because Chinese thought is not philosophy as understood in the West.

Classical Chinese had no word for “philosophy”, and the Mandarin term zhexue is a late-19th century import from Japan, initially used to refer only to Western philosophy.

As Sterckx points out, “In the pages that follow, you will find little theoretical reflection on how the human mind works, or whether there exists a world or reality beyond this one. Nor will you be told how matter relates to spirit, what truth is (let alone logic) or whether there exists such a thing called mind or knowledge.”

Nevertheless, Sterckx thinks we need to become better informed. His observation that young Chinese know more about “us” than we do “them” might have more force if what the Chinese teenager knows about “us” was material from Plato and Aristotle, or if they were typically anything more than only marginally less ignorant about Confucius or Lao Tzu than anyone else.

The classics are not exactly in vogue in China, except when convenient to the Communist Party – Confucius’ support for submission to authority is approved of; his exhortation to evaluate rulers critically goes unmentioned.

The same tendency in the West to romanticise China that leads to ill-advised tattoos of Chinese characters also leads to the false assumption that the antiquity of Chinese thought lends it special lustre.

Most ideas are offered as guidance to be lived, experienced and practised. They reflect on how to live, function better and find harmony with the world

But while the West may unreflectingly think, and the Chinese encourage the misapprehension, that Chinese thought is unfathomably old, Confucius (551-479BC) was a near contemporary of Socrates (circa 470-399BC).

Western philosophy students learn in their first-year logic classes that there’s nothing about the antiquity of a remark that makes it more persuasive, useful or true. Universal principles may have longevity, but the more practical reflections preferred in Chinese thought tend to become less useful as time goes by.

But perhaps the influence of ancient ideas is quite separate from any ability to quote from original texts.

After all, Aristotle (384-322BC), the inventor of formal logic, was influential on Christianity and Islam alike and remains embedded in Western thinking today, albeit unidentified as such by most. Everyone has to philosophise, argued Aristotle, because to argue against philosophy is itself to philosophise.

Philosophy in the Chinese sense rarely indulged in debate for its own sake, and dealt instead with the practical. “Most ideas are offered as guidance to be lived, experienced and practised,” explains Sterckx. “They reflect on how to live, function better and find harmony with the world.”

So far, so appealing, and Sterckx makes access easy. He opens with a chapter offering context – a description of the political situation at the time the thinkers lived, a discussion of classical Chinese language, and some notes on the nature of the source texts before setting out to define key terms such as dao and qi.

A handy table sets out the place of various thinkers in history, but otherwise their ideas are revealed not chronologically but in chapters tackling the issues they found of most concern: principles of government, the nature of ritual, the individual within society, relationships with spirits, and even food.

This makes it possible to dip into areas of particular interest.

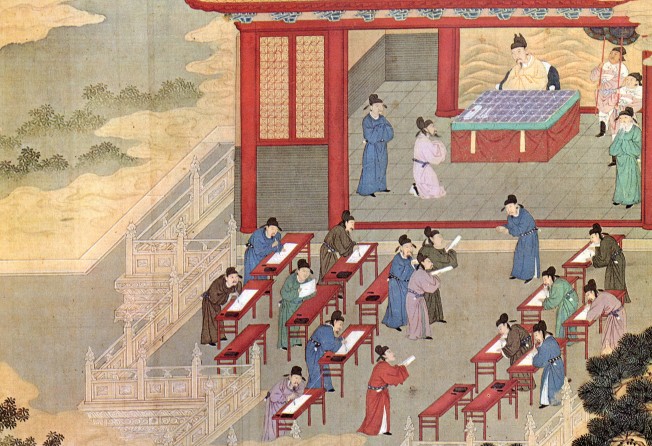

Most of the key thinkers lived in turbulent times such as the Warring States period (481-221BC), during which 10 or so single-ruler states contended, operating their own armies and government institutions, and registering their own populations for control and taxation.

There was neither time nor desire for the abstract. Each ruler surrounded himself with salaried advisers, and jobbing thinkers in search of a crust had to find employers who would pay for practical advice that helped to ensure their dynasties would endure.

The essence of survival was, of course, military success, so it’s no surprise that the chapter on the art of government opens with discussion of war-related texts, such as those in Sun Tzu’s Art of War (Sunzi Bing-fa) from the 5th century.

This is sufficiently fashionable to be the one text of which most English-speaking readers have heard, and one whose ideas have indeed had wider practical impact in their application to politics and business negotiations in general.

There’s not much else to help the entrepreneur. Confucius, who had nothing to say about military matters but much to say about leadership, naively believed that good moral character in leaders would lead to good behaviour in others. Given the widespread and well-documented corruption at the highest levels in China, such a belief does not bode well for business dealings.

Furthermore, Chinese thinkers, whether Confucians, Daoists or Legalists, were almost unanimous in placing merchants at the bottom of society, below scholar-administrators, farmers and artisans.

This, as Sterckx points out, “did not prevent China from developing into one of the most mercantile-minded societies in global history”. So how will traditional thinking help navigate China’s business environment? Allowing entrepreneurs close to government as former-president Jiang Zemin did would not have met with approval.

It is offering the best price, accepting contractual arrangements that will be unenforceable in mainland China, and showing a naivety with regard to quality control that will seal the deal, not knowledge of the BC Spring and Autumn Annals of Mr Lü (the Lüshi Chunqiu, a philosophical encyclopaedia compiled around 239BC).

There’s much that will seem far from alien to the Western reader. Physical events and moral behaviour are related, so Chinese thinkers saw natural disasters as caused, at least in part, by people, just as some today blame floods, earthquakes and tornadoes on tolerance of homosexuality.

Similarly, the Spring and Autumn Annals of Mr Lü link harmonious musical performance and cosmic harmony, Sterckx explains. “Music thus becomes a cosmic force: perform it well and you can advance ‘the harmony between Heaven and Earth’.” Cacophony, meanwhile, creates misbehaviour – an argument familiar to music enthusiasts, having been repeatedly disinterred with the arrival of rock ’n’ roll, heavy metal, punk and rap.

And there are parallels with Western philosophical texts. The Analects (Lunyu, a collection of sayings attributed to Confucius compiled long after his death) discuss one “Upright Gong”, named because he reported his father to the authorities for stealing a sheep.

Similarly, one Socratic dialogue finds the religious Euthyphro prosecuting his father for having killed a servant, an action the son regards as pious.

Just as Confucius regards it as “upright” for a son to cover up for his father, not denounce him, so Socrates shows by questioning Euthyphro that the man cannot even define the meaning of the “piety” he claims justifies an action of which both Socrates and the gods disapprove.

East and West appear to be in harmony.