Jung Chang’s new book on Soong sisters a long overdue account of three remarkable Chinese women

- The three siblings were known for marrying powerful men – Sun Yat-sen, Chiang Kai-shek and H.H. Kung, one of China’s richest businessmen

- Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister: Three Women at the Heart of Twentieth-Century China wipes away the nostalgic veneer and puts the men in their place

Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister: Three Women at the Heart of Twentieth-Century China

by Jung Chang

Jonathan Cape

4/5 stars

“One loved money, one loved power, one loved her country.” So goes the famous line about the infamous Soong sisters, the subject of the final book in Jung Chang’s epic trilogy on modern Chinese history.

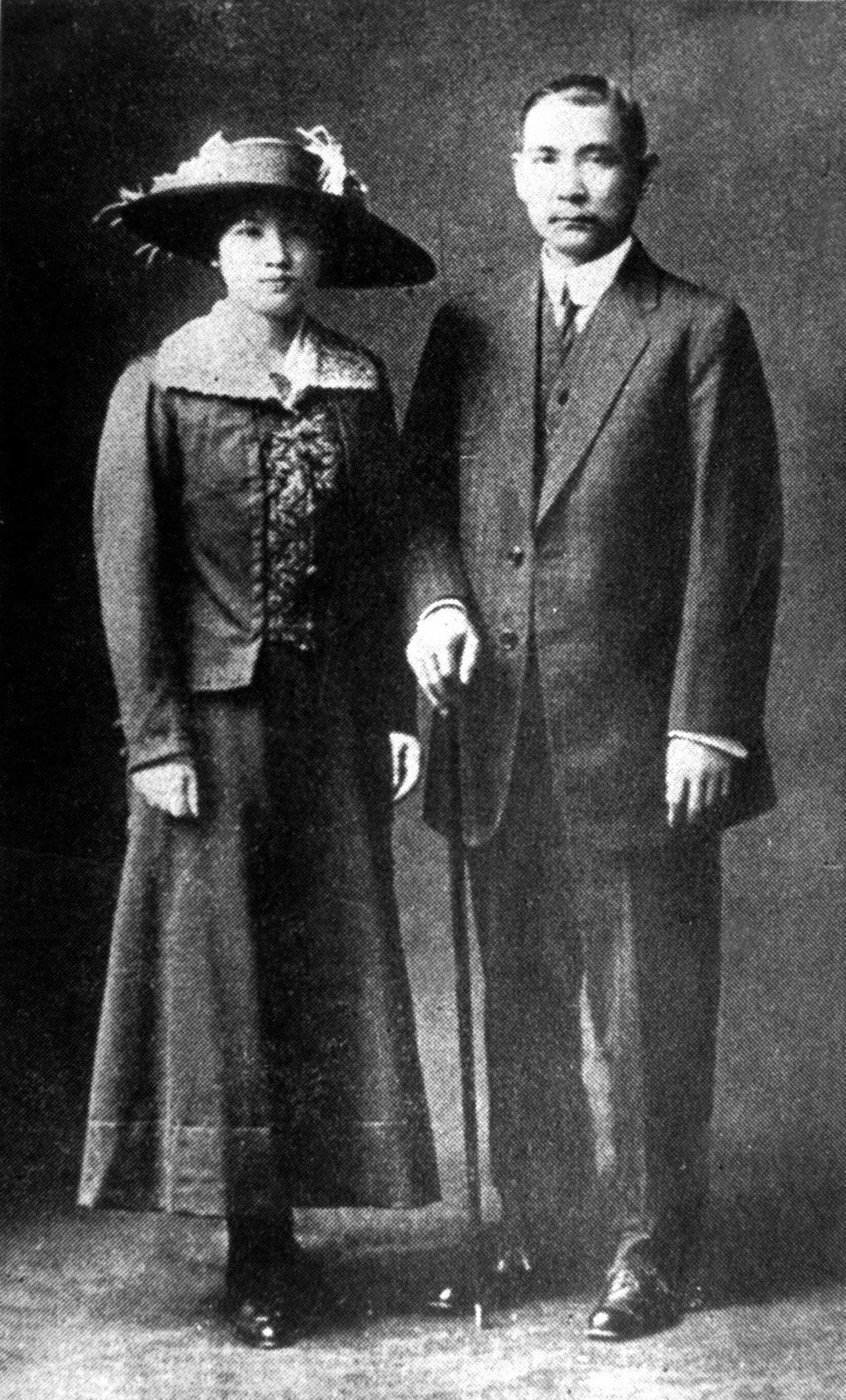

The Soong sisters are best known for their extraordinary taste in husbands. “Big Sister” Ai-ling married H.H. Kung, one of the richest men in China. “Little Sister” May-ling became Madame Chiang Kai-shek and wielded global influence from her perch in Taiwan, where her husband ruled for 25 years. “Red Sister” Ching-ling wed Sun Yat-sen, the father of modern China, and continued to be a revered Communist Party figure long after Sun died, in 1925.

The powerful trio, sometimes known as the Soong Dynasty, witnessed a century of Chinese history: the fall of dynastic rule; the rise of the republic; two wars against the Japanese; the split between the communist mainland and democratic Taiwan; and China’s economic rise. They also led exciting, jet-setting lives that took them from New York penthouses to secret meeting rooms in Moscow.

Given the sisters’ great influence, there have been surprisingly few books about them; the last two of note were published in the 1980s (one by Chang). Big Sisterrevisits their spectacular history, drawing on new sources.

In the introduction, Chang quickly does away with what she calls the “fairy tale” of the trio as exotic Shanghai seductresses, and pokes fun at the stereotypes often used to portray Asian women: “… [T]hey were not great beauties by traditional standards, their faces not shaped like melon seeds, eyes not resembling almonds and eyebrows no arching willow shoots.”

In Big Sister, each is brought to life. Chang paints deeply personal portraits of three very different women, starting with their schooling in America.

Ai-ling, who would become one of the richest women in China, was cool and demanding even at a young age. She became the first Chinese woman to be educated in the United States when she travelled, solo, at age 14, to Wesleyan College, in Georgia. She complained directly to President Theodore Roosevelt when she felt poorly treated at immigration (he apologised), and was so particular that she had 40 bolts of brocaded silk sent from China for her school production of Madame Butterfly.

Meanwhile, “Red Sister” Ching-ling was a “passionate and impulsive” girl, with politics in her blood and adolescent fantasies of being a Joan of Arc-type heroine. On hearing that China had become a republic, she tore the dynastic “Yellow Dragon” flag off her US dorm room wall, stomped on it and cried, “Down with the Dragon! Up with the flag of the Republic!” Unsurprising then that she fell in love with the brash rebel leader Sun.

May-ling, the future Madame Chiang, was the most Americanised of the three. She loved Western fashions, flirted with foreign men, and spoke more English than Chinese when she returned home from Boston’s Wellesley College.

But when she married Chiang, the then-head of the Nationalist army, she immediately understood her role as a political wife, switching to a uniform of silk cheongsam with high slits and a traditional hairstyle of straight-cut fringe. This cultivated look, combined with fluent English, would turn her into an international figure as Taiwan developed into a US ally.

On one publicity tour of the US, she stayed at the White House, addressed Congress and spoke to a crowd of 17,000 at New York’s Madison Square Garden, and 30,000 at Los Angeles’ Hollywood Bowl. At the 1943 Cairo Conference, she chatted easily with US President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, translating for her husband, who did not speak English. Starting in 1949, she helped Chiang build up Taiwanese society, using her influence to soften his hard militarism.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Taiwan Strait, the widowed Madame Sun – severe in black dresses and plain flat shoes – was portrayed in Chinese state propaganda as “a queen, a goddess and film star all rolled into one”. Ultimately, marriage put “Red Sister” and “Little Sister” on opposite sides of Chinese politics.

Ai-ling, a devout Christian and staunch anti-communist, had the stablest life of the three. She mothered three children and lived in affluence, using her husband’s government positions to control Chinese finances from behind the scenes. An American journalist wrote, “She is a first-rate financier in her own right.”

The other two sisters, for all their political glamour, were less lucky. Both suffered miscarriages and were rendered incapable of having children, in incidents that Chang links to their husbands.

In the more tragic case, Sun left Ching-ling in the presidential palace as “bait” under the charge of a rival army, to give him an excuse to bombard Canton. His military victory thrilled him, but it left his wife having to manoeuvre her own escape and she lost her unborn child. “The blow was crushing,” Chang writes. “Ching-ling longed for children. Heartache would shadow most of her life.”

May-ling also lost a pregnancy, due to the stress of repeated assassination attempts on her husband, including one in which two traitorous bodyguards entered their bedroom, with weapons at the ready, to shoot Chiang.

The men in the Soong sisters’ lives do not come off well in this book. Sun was known for his cold-hearted ruthlessness and ego. In Beijing, he was unmatched in his lack of scruples and hunger for power, which was fed by millions of dollars from foreign backers. Chiang is described as a “lecherous lout”, “delusional” about his powers and a “bully”.

Despite their tumultuous lives, there was a great bond between the sisters. When Sun was dying of liver cancer in Beijing, the two older sisters travelled north through the winter – when rail lines were closed – to comfort their younger sister. When Japan laid siege to China, the three fled to British Hong Kong, where they dressed up in their cheongsams and dined at the Hong Kong Hotel, the hottest club in town.

But in the end, politics pulled them apart. As “Red Sister” grew more radical, her older siblings became increasingly appalled at the revolutionary violence she endorsed. And so Ching-ling died alone in China, while Ai-ling and May-ling were buried together in their adopted home of New York.

Chang is a clever storyteller with a fine eye for personal detail. While Big Sister is a meticulously sourced history, it reads like a political thriller.

It completes her historical trilogy that includes Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China (2013) and Mao: The Unknown Story (2005), co-written with husband Jon Halliday. The works of Chang, whose bestselling memoir Wild Swans (1991) redefined the world’s idea of Chinese womanhood, is largely banned on the mainland. Only time will tell if her stories of China will someday reach her native land.