Kilsoo Haan – the Korean secret agent who warned the US about Pearl Harbour attack

- Biography of secret agent reveals US officials dismissed a Japanese attack as ‘a product of Haan’s imagination’

- Haan’s espionage network of low-level workers also warned of rise of communism in Korea

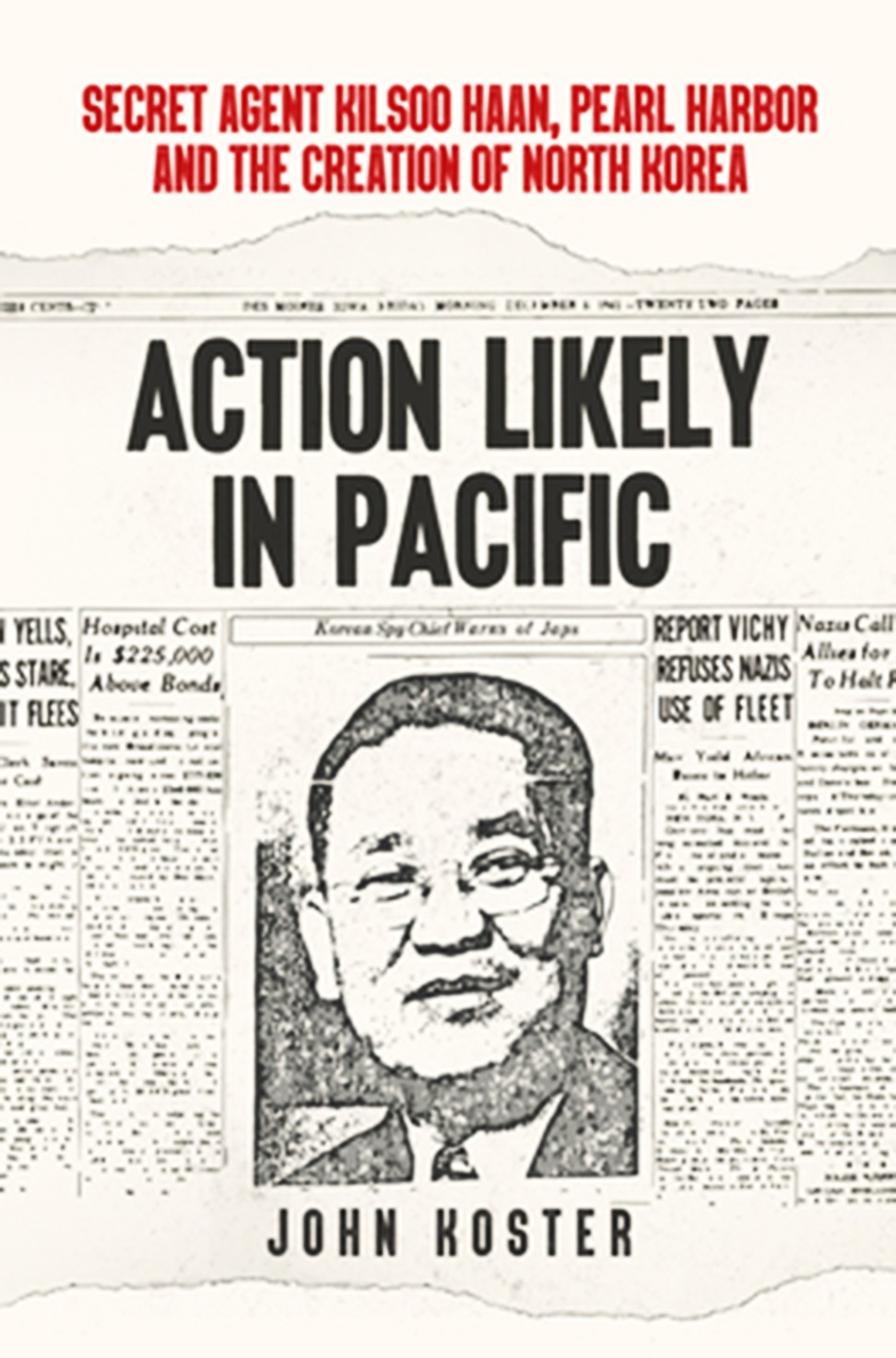

‘Action Likely in Pacific’, Secret Agent Kilsoo Haan, Pearl Harbour and the Creation of North Korea

by John Koster

Amberley Publishing

4/5 stars

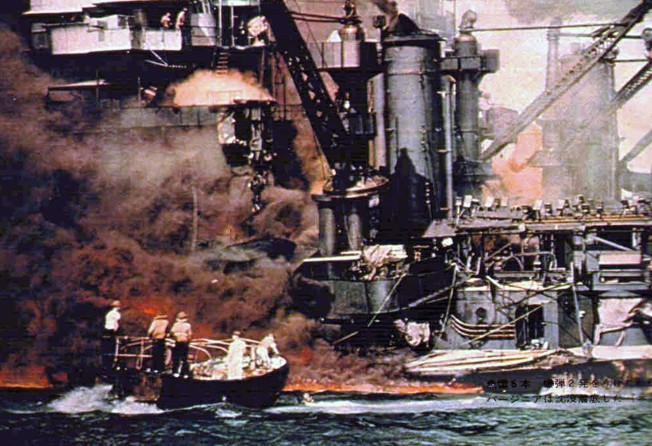

The official inquiry into the attack by Imperial Japanese air and naval forces on the United States fleet at Pearl Harbour, on December 7, 1941, reached a damning conclusion.

“Why, with some of the finest intelligence available in our history, was it possible for a Pearl Harbour to occur?” asked the 10-member committee looking into arguably the most stunning attack of the second world war. The report, released on June 20, 1946, cited “interdepartmental misunderstandings”, a failure in Washington to appreciate the looming threat, and “errors of judgment” in the US command in Hawaii as well as in the intelligence and war plans divisions of the war and navy departments.

The failure of the combined efforts of the US military, intelligence and political communities is even more remarkable given that one man knew what was coming weeks before December 7, a day that President Franklin D. Roosevelt, only hours after the attack, would describe as “a date which will live in infamy”.

Kilsoo Haan did not have high-level informants within the Japanese legation in Hawaii or Washington, DC. He had not broken Tokyo’s secret codes and was not surreptitiously accessing the diplomatic pouch. Instead a network of Koreans in low-level positions in Japan and its overseas possessions enabled him to piece together the big picture that the US was not seeing.

He also dug up his own clues, as John Koster reveals in the first biography of Haan, “Action Likely in Pacific”, Secret Agent Kilsoo Haan, Pearl Harbour and the Creation of North Korea.

Four days before the attack, for example, Haan, unable to sleep, went to a Chinese restaurant in Washington. At the next table, a Japanese man was trying to sell a secondhand car to a Chinese man. After the Japanese man left, the Chinese confided to Haan that the man had been from the Japanese embassy and was desperately trying to sell off the consulate cars at ridiculously low prices. They were being sold off cheaply, he said, because all the embassy staff were about to return to Japan.

That new intelligence set alarm bells ringing and Haan again contacted the State Department, warning: “Japan may suddenly move against Hawaii this coming weekend.”

Haan had already written directly to Roosevelt, Secretary of War Henry Stimson, a succession of senators and anyone else he considered to have influence to warn them of what lay over the horizon. But he was continually rebuffed. Haan later told a journalist that US officials believed talk of a Japanese attack was “a product of Haan’s imagination – anti-Japanese propaganda”.

The day after the Pearl Harbour raid, Washington’s tune changed dramatically, Koster reveals. A senior official at the State Department telephoned Haan to say he would be “put away for the duration” if he told the press about the numerous warnings he had provided to the US government.

Koster’s remarkably well-researched book makes it clear that Haan’s motivation for sharing his insight with the US was his burning hatred of Japan, which had invaded the Korean peninsula when he was a boy and subjugated the nation. He had a similar dislike of Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union, which he saw as an opportunist that would meddle in Korea’s affairs for its own ends.

Born in the then independent kingdom of Korea, in May 1900, Haan and his parents emigrated to Hawaii three years later. He worked in sugar-cane fields between his studies at a Korean school on Oahu. His father returned to Korea in 1910, but Haan stayed in Hawaii with his mother. In 1920, he went to San Franciscoto join the Salvation Army Training School in preparation for entering the church. Back in Hawaii, on the island of Kauai, he rose to the position of captain before leaving the organisation in 1926 to marry a Korean woman from Honolulu named Stella Yoon.

Driven by his dislike of the nation that had conquered his homeland – a hatred driven to new heights by the Nanking massacre – Haan set about building a network of reliable sourceswho would give him a full picture of Japan’s ambitions and military planning for the Asia-Pacific region. The detail he managed to glean from these reports is remarkable; that so much was accurate is even more extraordinary.

Haan’s first breakthrough came in September 1940, when his sources in the Korean underground – either at the Japanese consulate in Honolulu or, more plausibly, shipyards in Japan – reported the secret construction of midget submarines. He was unable to get government officials or military leaders interested in the reports, but journalists were more open to the story and The Washington Post and The New York Herald Tribune both ran his allegations.

Haan correctly informed the US that Japan would attempt to infiltrate Pearl Harbour with midget submarines. He also warned that Tokyo was planning to drop bombs laced with plague germs on San Diego from aircraft that had been ferried across the Pacific aboard huge submarines – an attack that was only called off late in the planning stages.

Much of the book is necessarily devoted to the military and political manoeuvring of the time. Though, it would have been interesting to learn how Haan set up his network of agents, who they were, how they operated, and how top-secret information was obtained and communicated. With the protagonists long gone, it is unlikely the stories of these individuals – who took more risks than Haan and many of whom probably died for their convictions – will ever be fully reported.

Haan’s espionage and intelligence work did not end with the defeat of Japan in 1945. As a Korean patriot who wanted the best for his homeland, he turned his attentions to preventing a communist leadership – backed by his old enemies in Moscow – from gaining control over the northern half of the peninsula. But just as in 1941, US politicians were slow to recognise the danger and respond to Haan’s warnings. Their mishandling of the situation contributed to the crowning of Kim Il-sung as dictator of North Korea.

Undeterred, Haan continued to tap his network for information on the Soviet Union’s development of guided missiles and nuclear testing in Siberia. He even accurately warned of the impending North Korean invasion of the South, in 1950, which led to the three-year Korean war and the deaths of millions of United Nations troops and non-combatants.

Haan’s tale is, in part, almost too astounding to be true, occasionally edging into the realms of James Bond. But his achievements should have been recognised and documented long ago. Koster’s book goes a long way to righting that wrong and is an important addition to our understanding of the heroic work of a few brave and committed individuals in the face of enormous odds.