When translating Chinese into English could be dangerous – Britain’s failed 1793 embassy to China seen through interpreters’ eyes

- Britain’s Lord Macartney’s interpreters for his embassy to China’s Qianlong emperor were an exiled Chinese priest and a boy who’d had a crash course in Mandarin

- The priest stayed on in China but was a wanted man; the boy grew up, went back there, translated for a second embassy but fled after threats from the emperor

The Perils of Interpreting – The Extraordinary Lives of Two Translators between Qing China and the British Empire by Henrietta Harrison, pub. Princeton University Press

Often the most readable books on Chinese history are those that use detailed accounts of the lives of individuals to illuminate the great events of their time.

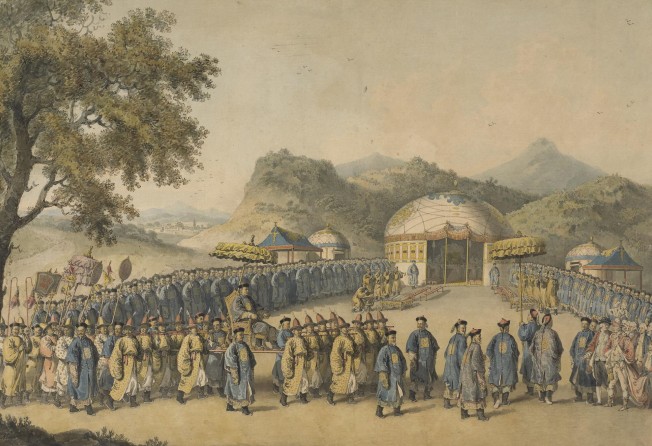

Oxford professor Henrietta Harrison’s The Perils of Interpreting – The Extraordinary Lives of Two Translators between Qing China and the British Empire is a fine example, providing a fresh description of the 1793 embassy from Britain’s King George III to the Manchu Qianlong emperor through the eyes of those who mediated, rather than those of the principals.

“Many interpreters in the 18th century acted as negotiators rather than mere translators,” Harrison tells us, “and they attempted to explain the thinking of their masters in terms they felt would be understood, rather than providing a literal translation of what had been said to them.”

Events were often shaped by such suppliers of information, and just as underlings could avoid imperial wrath by telling the emperor what he wanted to hear, or at least concealing bad news, so interpreters could tailor the language of their translations to make it less combative, or de-emphasise or omit sections altogether, with the aim of bringing two sides together.

But this position of control over negotiations could earn the suspicion of both sides, and put interpreters in peril.

Lord Macartney, Britain’s first ambassador to China, was particularly keen to avoid hiring anyone already working in Guangzhou’s foreign trade who might have commercial interests too close to his heart, or any Beijing-based Jesuit mainly interested in the welfare of his order or of the Catholic Church as a whole.

He sent his deputy, Sir George Staunton, to continental Europe to look for returned missionaries who, on the long voyage back to China, might reveal their own particular biases but also become intimate with the embassy party, and as a result zealous in pursuit of its interests.

But Staunton’s main recruits, including one of Harrison’s subjects, were Chinese who had been sent as children to Naples by the Catholic Church to be raised as priests. Li Zibiao was born in 1759 to a Catholic family in what is now Wuwei, in China’s northwest. He was fluent in Latin, the lingua franca of the educated in 18th century Europe, which he used to communicate with the embassy en route.

It was expected that the Chinese on board should instruct the English members of the embassy in their customs. Staunton’s son, Harrison’s second subject, spent the voyage learning Mandarin, and at the age of 12, acting as Macartney’s page, found himself stammering out words of thanks to the Qianlong emperor for a gift received, to the astonishment and delight of those present.

With his father’s encouragement the younger Staunton went on to gain an excellent knowledge of the language. He later returned to China as a merchant, and for the Amherst embassy of 1816. His reappearance on the diplomatic scene brought threats from the Jiaqing emperor, Qianlong’s successor, and he was forced to quit China for good in 1817.

But the translation of intent that the younger Staunton advocated mattered. If the Mandarin yí was translated as “barbarian”, for example, hackles would rise, and agreement become less likely. Both Li and Staunton preferred the translation “foreigners”, but those traders determined to attract military support for the opening up of trade insisted on “barbarian”, thus recruiting to their cause members of parliament touchy on the subject of their own superiority.

Later an MP himself, Staunton “complained vociferously that this translation was morally wrong because it ‘tends to widen the breach between us and the Chinese’,” Harrison writes.

Li subsequently lived a fugitive life, remaining in China to work as a priest in remote rural communities. Clampdowns on Christianity came and went, but having been an employee of a foreign power and privy to the thinking of its representatives, Li was permanently a wanted man.

Harrison provides a modern twist when she compares the “Chinese-inflected Marxism” of modern Chinese political debate with the allusive language of classical Chinese. Both of these frame modern interactions in historical contexts, and if translated word for word become equally stilted and unclear.

Conveying Chinese political ideas in plain English is as much a problem for translators and interpreters today as it was three centuries ago. But as Harrison shows, back then it could be downright dangerous.