Why the Philippines isn’t more influential in Asia: corruption, apathy about regional issues and lack of national interest, says new book

- The Making of the Modern Philippines: Pieces of a Jigsaw State, by Philip Bowring, looks at why the nation ‘punches below its weight’ internationally

- The author attributes this to a mix of corruption, the influence of family dynasties, and a lack of national pride

The Making of the Modern Philippines: Pieces of a Jigsaw State, by Philip Bowring. Published by Bloomsbury Academic

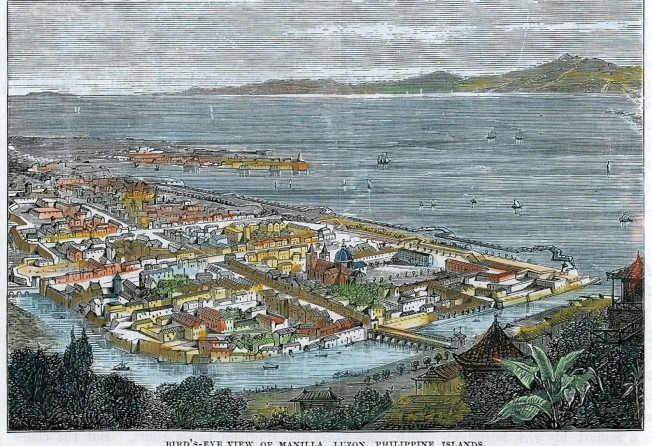

Years ago, while taking a friend and other Europeans around the Spanish colonial walled area of Intramuros, in Manila, I was asked by an Austrian, who had clearly done some research: “The Philippines is a big country with a large population, more than 100 million people. Why isn’t it more influential in Asia?”

The question probably doesn’t occur to most Filipinos. But it is addressed in The Making of the Modern Philippines, by Hong Kong-based journalist and editor Philip Bowring, whose new work is a follow-up to and an expansion of Empire of the Winds (2018), a history of Nusantara, the maritime states of Southeast Asia.

“It certainly punches far below its weight internationally,” he says of the Philippines. “There is scant interest in international and especially regional issues among the elite and media.”

Southeast Asia’s second most populous country, the Philippines seems detached from the region, indifferent to and unengaged with its neighbours. They, in turn, are baffled by Philippine international behaviour and upset at how the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte in 2016 threw away the Philippines’ maritime arbitral victory over Beijing in favour of closer economic ties.

“I think there’s a lack of effort on the part of the Philippines to engage with its immediate neighbours more closely,” says Bowring. He recalls a conversation 20 years ago with the Vietnamese ambassador in Manila and how “he was so frustrated about the Philippines’ wishy-washy attitude towards its claims on the South China Sea”.

“And Duterte comes in and throws away [the arbitral win], the best leverage of the country,” Bowring continues. “[The other maritime countries in Southeast Asia] didn’t expect it. It causes other people to be rather surprised about what this country really wants. Where is its pride? Where is its national interest? Who’s protecting its national interest?”

The Making of the Modern Philippines is divided into two parts: a history of the Philippines from pre-Hispanic times right up to 2021, and a series of chapters that provide a detailed political and economic analysis.

A clue to why the country is the way it is lies in the book’s subtitle: Pieces of a Jigsaw State. An archipelago of about 7,640 islands, of which 2,000 are inhabited, the Philippines is fragmented geographically. It’s also fragmented politically: although the country is a democracy, power lies in the hands of families that constitute an oligarchy and build dynasties that use their wealth to hold and win office for their benefit.

The glue that’s supposed to hold the country together – nationalism, language, a sense of identity, a strong government – doesn’t quite gel.

“Senses of nationalism and civic duty appear weak compared to the demands of kinship and client relationships, blurring lines between public and private spheres,” he says.

Bowring notes that although “there is a national language (Pilipino, based on Tagalog), at the same time there isn’t, in the sense that it’s not widely used”.

When these factors are mixed with massive corruption, poverty and personality-based politics, the result is a nation unable to focus, its policies constantly drifting and subject to the vested interests of political dynasties. Because of bad governance and corruption, most indices show the country standing still or even moving backwards.

Bowring notes how, for decades, Philippine growth has relied on remittances of overseas workers as well as earnings from call centres. “Agriculture and manufacturing are really very weak. Educational levels are now deemed the lowest in the region, having had at one time the best primary education anywhere in the region apart from Singapore”.

Bowring, who has visited the Philippines frequently since 1973, says that “when you look back nearly 50 years, you think how little has changed, and that’s the sort of fundamental problem that you don’t find in neighbouring countries, except Myanmar”.

As a nation, the Philippines needs to be taken more seriously by itself as well as by outsiders

He says that when speaking to Filipinos about their country, “there is an awareness that things have not gone very well, that people shouldn’t have to emigrate in order to feed their family”.

Now the country’s dark past is revisiting it with a vengeance: just days before the May 9 presidential elections, the candidate leading the polls is Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jnr, the unrepentant son of the dictator whose 14-year martial law regime murdered and tortured thousands of people, and pillaged the economy.

Asked if it’s possible to see a tyrant rehabilitated this way in any other Southeast Asian country, Bowring says, “You see the efforts going on in Malaysia on that very same topic, but in the case of Bongbong Marcos, it’s just that he’s got a younger generation who actually know nothing, have no experience of what it was like under martial law, or what legacy of theft was left by Marcos.”

In the book, he writes how “by some measures, the Philippines needs a revolution, to throw off the old elites, end monopolies, open up to foreign competition, prioritise education, eliminate large-scale smuggling and enforce taxes”.

Ruled by Spain for 333 years and by the United States for 48 (with three years of occupation by Japan during World War II), the Philippines is a product of its colonial experience.

“The colonial history and the American magnet do create some distance between it and the Asean core,” Bowring says. But, he notes, even Asean itself “is increasingly marginal as the forces which put it together have weakened and US/China rivalry will continue to divide it. The Philippine failure now is lack of focus on its common interests with maritime neighbours and its Austronesian cousins.”

The Making of the Modern Philippines, Bowring says, fills a gap for a broader analysis of aspects of the contemporary nation “linking past and present and trying to show continuity of history”.

In so doing, the book provides insight into what Filipinos think about their country: the most common reply to the question, he says, is “disappointment”.

“Obviously, there are places that are in worse condition,” Bowring says, downplaying its “sick man of Asia” label. “But, certainly, I think it’s been a disappointment for anybody interested in the country.”

So why does the Philippines lack influence in Asia?

“As a nation,” he says, “the Philippines needs to be taken more seriously by itself as well as by outsiders.”