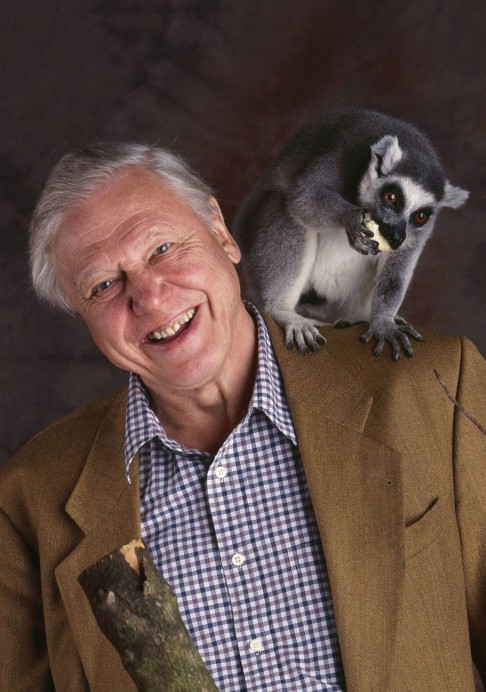

David Attenborough at 90: TV's last colossus looks ahead

Virtual reality the next frontier for BBC broadcaster and naturalist, who turns 90 on May 8 still full of wonder at the 'glory of life' and as reticent as ever to talk about his least favourite subject - himself - writes Etan Smallman

David Attenborough is tired. It is written all over his voice. Those deep, languid vowels elongate and the breathy drawl becomes even more exaggerated than those of the many mimics who have attempted to imitate his famous whispers.

In fairness, the star is on the cusp of 90 (he was born on May 8, 1926, in Isleworth, west London), but that isn't what's holding him back - as prolific as ever, he recently enjoyed a jaunt to the Great Barrier Reef, has just been filming luminous earthworms in France and dropped by Argentina to see the largest dinosaur fossil ever found being dug up.

The weariness is more to do with him burning the midnight oil the previous evening, filming the BBC's tribute programme for his milestone birthday ("It isn't what I'd do for an evening off") and being up bright and early for a raft of interviews at a fancy hotel near his home, in the leafy west London suburb of Richmond.

Despite the lack of sleep, a mention of tardigrades (1mm-long creatures that are virtually indestructible) jolts him into enthusiasm. Talk of a pufferfish or peacock spider instantly perks him up. And the fact that I'm here for the South China Morning Post's Post Magazine has him gushing with interest.

"Ask me about it - I'll tell you about south China," he effuses. "Kunming. I could tell you more things about Kunming than you've had hot dinners. And I've filmed in that area. It was fossils … feathered dinosaur fossils."

However, venture on to the topic of the great man himself and you half expect him to stifle a yawn. For once you start probing Attenborough, you quickly realise that, of all the many thousands of creatures that exist across the globe, there is only one in which he exhibits almost no interest whatsoever.

I say I'd like to ask him about "the voice". "Ah yes, would you like a bit of Schubert?" he replies without missing a beat.

Is he conscious of his trademark vocal delivery? Has he cultivated it over the years? "Are you conscious of yours?"

No, but then no one's listening to me. Attenborough slowly leans in and narrows his cornflower blue eyes in mock pity. "Ahhh," he yelps. "Ahhhhhhhhhhhhh."

Kunming. I could tell you more things about Kunming than you've had hot dinners. And I've filmed in that area. It was fossils … feathered dinosaur fossils

He sits back in his chair with a chuckle, before concluding, "No, that's the way I talk, I'm afraid. There's nothing much I can do about it, really," as if addressing the most boring subject on the planet.

If his majestic vocal cords were just something he happened to have been blessed with, he almost gives the air that his whole career has been a series of happy accidents. You see, British television's most revered star grew up without a television. What luck that the birth of Attenborough coincided almost exactly with that of "the box" (which was first demonstrated to the public in London's Selfridges department store in 1925).

Moreover, what a blessing that the start of his life at the BBC coincided with the advent of commercial air travel. It has led Attenborough to become - by many accounts - the man who has seen more of the world than anyone else. And the explosion of technological innovation has repeatedly placed him at the cutting edge, even into his 80s. He is the only person to have won Baftas (British Academy of Film and Television Arts awards) for programmes in black and white, colour, HD, 3D and 4K (high resolution).

Virtual reality is his next frontier, but Attenborough, dressed in blue jacket, blue chinos and a crisp white shirt to match his glossy mane, claims he can "barely work a mobile phone". He talks of the mystery of nature before pointing at my digital voice recorder. "I'm mystified by these things." He starts pawing at the air: "And indeed the fact that up here somewhere, there are the Beatles playing. I know because if I have the right bit of kit, I can get 'em." He jokingly clarifies: "When I say 'Beatles', I don't mean 'buzz buzz', I mean 'twang twang'."

We are all familiar with his natural history programmes, naturally, but the broadcaster also presided over the BBC's first knitting shows, in the 1950s, and went on to produce Queen Elizabeth's Christmas broadcasts. As controller of the BBC2 channel when it was new, he commissioned the first series of Monty Python, in the 1960s, and brought colour television to Europe (beating the Germans to it was a particular thrill).

Is there an underlying mission that drives him to keep pioneering into his 10th decade?

"You know, someone once said to [Hollywood producer] Samuel Goldwyn …" - Attenborough adopts an American accent - "'In your films, are you trying to send a message, Mr Goldwyn?' And Mr Goldwyn said, 'If I want to send a message, I'll use Western Union.'

"That's the same for me, really. Obviously I care about conservation and about the state of the natural world, but I'd much rather just be making films about the glory of life, films which just said, look at this, this and this - absolutely fascinating and wonderful and beautiful and marvellous!"

For someone who finds himself so ordinary, the fuss and flattery must seem peculiar.

When describing Attenborough's achievements, you quickly run out of superlatives. You also risk running out of space on the page if you give him his full, glorious title: Sir David Attenborough OM (Order of Merit) CH (Companion of Honour) KT (Knight of the Thistle) CVO (Commander of the Royal Victorian Order) CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire) FRS (Fellow of the Royal Society) FLS (Fellow of the Linnean Society) FSA (Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London). Before the recording of his TV special began, the show's presenter, Kirsty Young, admitted to the audience: "I like to call him God, actually. The greatest man on Earth."

Is this a person he recognises? "No," the zoologist says emphatically. "I mean, come on. You know, those are very nice things to say but you of all people know what your frailties are. And if you're going to ask me what they are, I'm not going to tell you," he laughs.

"Oh sure, it's embarrassing, yeah. I mean, in your heart, you think, 'You've conned 'em. Oh well, you've got away with it this time.'"

Chatting to current and former colleagues of Attenborough, the same words crop up again and again: "professional", "modest", "humble", "generous". And his 65-year career has been conducted without any hint of scandal, with his private life remaining remarkably private. I defy you, for example, even to tell me how many children he has. (The answer is two: a son, Robert, and a daughter, Susan, to wife Jane, who died in 1997.)

Yet surely there must be another side to the naturalist. Young attempted to find one, saying: "I have been told that by the time you got to secondary school, would it be fair to say, there was something of the rebel in you?"

Attenborough wasn't having any of it. "Rebel? What was I rebelling about? I was a conformist type of chap … I had a bicycle …"

So I try where Young failed. I recount to him that as I walked among the audience at the London Studios, next to the River Thames, I overheard one collaborator let slip: "People keep asking me for Attenborough stories - most are unrepeatable. He's a bit of a boy on tour."

"Really? Oh well, I'm learning things," he replies with a cherubic grin. But is there a naughty side to the broadcaster that BBC viewers never get to see?

"Oh, not naughty, not in a serious naughty way. No, of course not. No, we have a good time. There's a lot of pleasure to be got from achieving things working as a team, no more than playing rugby or football."

There is certainly a serious side. He learnt of the horrors of the world as a child when they intruded into his own family. His parents fostered two Jewish refugee girls, Irene, 12, and Helga, nine, fleeing from almost-certain death under the Nazis. And he thinks his suffragette mother and academic father, were they alive today, would be opening their home to Syrian children.

"I'm sure my parents would, yes. When you're 12, compassion and understanding, well, they're limited - little boys are rather selfish.

"I just wonder how they would deal with the current situation, where it isn't a question of taking two children or even 50 children, we're talking tens of thousands of people. And it's irresponsible to say, 'Oh yes, of course we would help them!' That doesn't answer the question."

His early BBC career was also formative. Attenborough seems to have been stung by criticism that he was slow to the party on climate change, but his training in the 1950s had left its mark.

"Part of my problem, if it is a problem, is, you see, I was reared as a BBC broadcaster. We regarded it as being beyond toleration that anyone should ask you what your political affiliation was. So when, by accident, I found myself in front of the camera, I still had that basic stance, that I wasn't there to grind an axe. And for that reason I was, if anything, somewhat behind the business of climate change. But the time does come when you have to make a stand."

A decade ago, he condemned United States president George W. Bush as being the era's top environmental villain. He isn't in the mood to hand out a similar accolade today, contending: "I think you're putting a moral loading on it that is unfair."

The Chinese are now very aware of what the problems [of climate change] are. It isn't easy just to say, 'Oh yes, we recognise the problem, therefore we will do this and this.' You've still got to have light in your homes.

And he is much more sympathetic to the climate change response of China than many of the country's critics.

"The Chinese are now very aware of what the problems are. It isn't easy just to say, 'Oh yes, we recognise the problem, therefore we will do this and this.' You've still got to have light in your homes.

"I mean, they took some pretty severe steps about population. And there will be plenty of people over here who would say that was inhumane. But, nonetheless, there would be a few million more people in the world now had the Chinese not taken that view."

For the TV special, Prince William recorded a video from Kensington Palace in which he refers to Attenborough in the same breath as the queen: "Two national treasures." Remarkably, the pair are celebrating their 90th birthdays within 17 days of each other. Have they shared notes?

"Not on geriatric moments, no! I think she must be ageless. You must insist that she's ageless." And how will he celebrate his big day?

"Hide under the bed, I expect."

As vital and present as Attenborough is, in many ways he resembles the last of his species - the last surviving of three brothers (including the actor and Oscar-winning director Richard), the last colossus of his industry. As he reflects on a life well lived, what hope does he have for the state of the world another 90 years down the line?

"Ninety years more!" he says incredulously. "Well, what would alarm me is the graph of human population. I mean, whatever we are going to do, it's going to go on climbing. And in 90 years, I think it will be absolutely possible that people will be saying, 'Well if you want to know what that animal is that's in the textbooks, you'll have to go back to the natural history films they made at the beginning of the 21st century.'"

If Attenborough has his way, of course, the people of 2106 will have both the films and the animals to marvel at. But we are lucky enough to still have the man himself to guide us around the wonders of the world while occasionally delivering some considered rebukes about how we're imperiling it.

The queen may be hogging the birthday headlines but - no matter how much he hates it - the king of the jungle, the savannah, the rainforest and the ice caps deserves adulation, too. Long may he reign.

Attenborough at 90 will be aired on BBC Earth next Sunday at 5.55pm. TVB Pearl will be showing three celebratory documentaries on consecutive Tuesdays, beginning this week with Attenborough and the Giant Dinosaur, at 9.35pm.