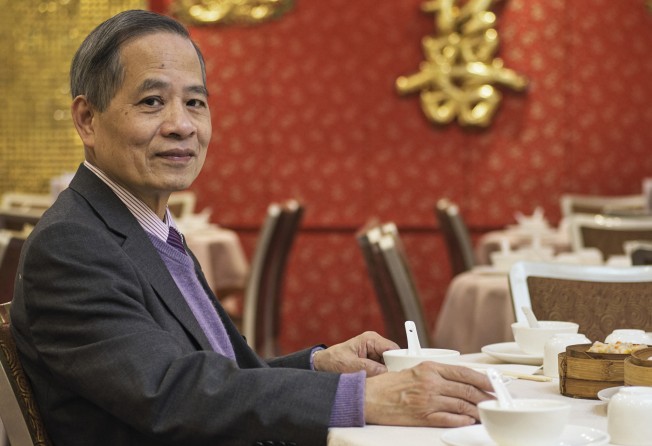

‘He represents what Chinatown stands for’: London chef turned restaurant owner Lee Shun-bun, born in Hong Kong, is 71 and still hard at work

- Lee Shun-bun arrived in the UK with little money and, after 15 years of hard work and sacrifice, opened his own Cantonese restaurant. Another followed in 2013

- Now 71, he talks about the changes in Chinatown as tastes have evolved, and the responsibility he feels to keep Chinese culture alive for younger generations

Lee Shun-bun is the last of his kind, the only restaurateur left of his generation of Chinese immigrants in London’s Chinatown.

He is also much more than a restaurant owner – over the decades, he has become Chinatown’s kingpin, keeping Chinese culture alive through his role as chairman of the Chinese Chamber of Commerce UK, and someone the community turns to for support and advice.

In 2022, his contribution to Chinese food in Britain was recognised with a lifetime achievement award in the Observer Food Monthly Awards 2022, presented by British newspaper The Guardian. Lee was put forward for the award by Andrew Wong, of London’s A. Wong, the first Chinese restaurant outside Asia to earn two Michelin stars.

Wong’s grandfather and Lee were friends, but Wong says Lee’s influence goes far beyond social circles.

“Mr Lee’s contributions to his community, his work with the chamber of commerce and its Chinese language school in Soho, and the knowledge he has from being here in the hospitality business for so long – to him, these things are nothing, just him wanting to share what he knows,” says Wong.

“But he represents what Chinatown stands for, and how the Chinese community is perceived here stems from the perception of Chinatown.”

When we meet at his restaurant, New Loon Fung, on Gerrard Street, Lee looks dapper in a shirt pinstriped in lilac and a matching violet tie. The sprightly 71-year-old says that, despite weathering five decades in the hospitality industry, he has no immediate plans to retire.

“I would say I have another 10 years of energy left to run this restaurant,” he says with a smile.

Over the clink of cutlery and the scent of jasmine tea, he tells me how it all began, a tale of immigration that echoes those of many people who left Hong Kong in the post-war decades to go west: arriving with very little, and building a life through hard work and sacrifice.

In Lee’s case, he landed in Britain in 1975, with just £300 in his pocket. What he did possess, however, were enviable dim sum-making skills.

He had dreamed of studying at university, but his father had died when was 12, leaving his brother and sister to look after the family. Not wanting to be a burden, he finished his schooling and went straight into culinary training in Hong Kong, with two years spent perfecting the intricacies of dim sum.

“I was accepted by the University of Alberta to study there, and probably could’ve scraped together the first year’s tuition fees, but what about year two and three?” he says, recalling the crossroads that changed his trajectory from Canada to Britain.

“When a friend managed to get me a work permit in the UK, where Chinese cooks could find good work, that’s where I went.”

He arrived in Britain aged 23 and went straight into the kitchen. He also enrolled at night school, but found it impossible to balance studying with work.

His dwindling finances dictated his decision to choose bao over books, dumplings rather than desk work. He continued to work in restaurants across London’s Soho district, eventually becoming a partner in some.

In 1990, he opened Harbour City a couple of doors down from where New Loon Fung is now. For the first few years, he led the kitchen, creating the outstanding dim sum the restaurant was known for, before moving to front of house. The restaurant quickly became a favourite, then, over the years, an institution.

In 2013, Lee opened New Loon Fung, which he ran alongside Harbour City. But, over time, Chinatown changed. Twenty-five years after he first opened its doors, he closed Harbour City. The site is now occupied by a Sichuan restaurant.

“There are now only two or three Cantonese-style restaurants on this street, where there used to be many. Chinatown has changed a lot,” he says. As China opened to the world, and knowledge of Chinese food spread globally, locals and visitors began to seek out previously unknown regional cuisines from Xinjiang to Hunan.

The influx of students and tourists from mainland China in recent years has also changed the fabric of Chinatown: wanting a taste of home, they flock to Soho’s streets in search of Beijing-style hotpot and Sichuan mapo tofu.

But Lee’s Hong Kong classics, his siu mai and char siu bao, still pull in a crowd, particularly older diners.

“I’ve been here a long time, and so have many of my customers,” he says. “Some regulars come every day, or every month. This is the only place I get to see them.”

These are challenging times for restaurateurs in Britain who, having navigated the Covid pandemic, are now facing staff shortages and a cost of living crisis that has seen the price of supplies and energy costs skyrocket. But Lee says he has not raised prices at New Loon Fung.

“It’s difficult to make a profit at the moment, but many of my customers are retired, on pensions, and I know they couldn’t afford it,” he says.

New Loon Fung does see younger diners, however, especially on Sundays for yum cha, when Lee meets his friends’ children and grandchildren.

“I feel it’s my responsibility to keep our culture alive with the younger generations through dishes such as Mid-Autumn mooncakes and Chinese New Year yau gok [fried dumplings],” he says.

He has ensured that his own children, born and raised in Britain, are schooled in Chinese culture. But when it came to their careers, he did not want them following in his footsteps. As with many immigrant parents, he wanted his children to have a profession.

“My only regret is that I didn’t get enough time to spend with my children as I was always in the restaurant,” he says. “I don’t want the same to happen to them.”

Yet the culinary world, despite its pressures, still has its allure. His daughter, Kaman, is a nutritionist, and his son, Sunny, runs a Hong Kong-style bakery and restaurant in north London.

In another decade, when Lee believes he may – possibly – retire, will his children take over the reins? That remains to be seen.

After a lunch of Lee’s exceptional cheung fun rice noodle rolls and Hong Kong-style egg tarts, I weave my way through tables stacked with bamboo steamers.

I step out onto Gerrard Street, its lamp posts strung with the red lanterns that symbolise Chinatowns everywhere. The sound of Cantonese fades. A lone ginkgo tree drops its yellow winter leaves on the pavement.

Everything has its season, and evolution is inevitable. But, for now, Lee continues to defy the march of time, preserving a taste of classic Hong Kong in an ever changing world.