Exploding toilets, diseased baths and flooding cesspits: how civilised were the Romans?

While all-conquering empire spread sanitation far and wide, Romans didn’t use soap and didn’t understand how parasites spread – and we don’t know how often the bathwater was changed

If there’s one thing most people know about the ancient Romans, it’s that they spent a lot of time in the bath.

As the Roman Empire grew, public baths proliferated across newly annexed territories. From plain and practical to polished-marble luxury, baths provided both colonists and colonised the means for a daily soak. Less well known is the Roman passion for another hygienic innovation: the public convenience. Wherever the Romans went, they took toilets.

What did all that washing and flushing do for the health of less fastidious folk who came under Roman rule? “Given what we know now about the benefits of sanitation, you might safely assume this would lead to an improvement in people’s health,” says Dr Piers Mitchell, a palaeopathologist at the University of Cambridge.

But hard evidence was lacking, so Mitchell went in search of it. He scoured records of Roman remains from towns and graveyards, and fossilised faeces, for parasites such as intestinal worms, lice and fleas. He found precisely the opposite of what he expected.

According to legend, Rome was founded in the 8th century BC. Two centuries later, work began on the Cloaca Maxima, or great sewer, which eventually became part of an immense network of drains and underground channels. Work on the first of the city’s remarkable aqueducts got under way in the 4th century BC. By the end of the 1st century there were nine, carrying more than enough water for drinking, bathing, flushing the streets and staging mock naval battles in a purpose-built lake.

By then, Rome was the world’s biggest city, with a population of a million, mostly living in squalid tenements in dirty narrow streets. Yet most people had access to public baths and toilets, the much-travelled Romans having acquired the technology from their Greek neighbours centuries earlier and built bigger, better and more of both.

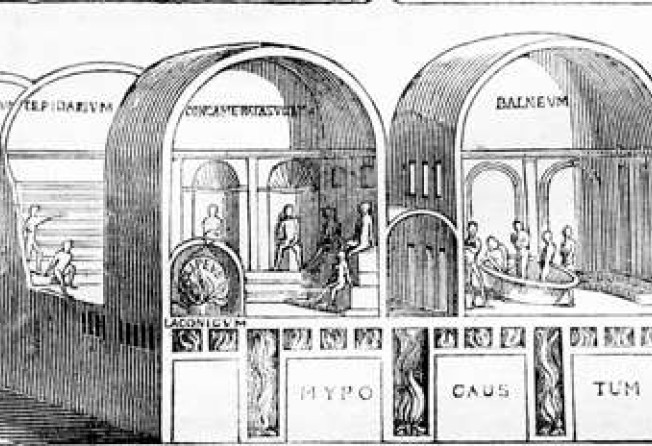

For most Romans, personal cleanliness was a matter of pride and bathing a daily ritual. The city had 200 public baths of varying sizes and degrees of luxury – places to relax, socialise and wash off the day’s dirt. Toilets were ubiquitous; private houses and tenements had latrines that seated several people at a time, while some public lavatories could accommodate 50. The authorities, keen to keep the city clean, introduced laws requiring human waste and rubbish to be removed outside the city.

As Rome’s tentacles stretched ever farther across Europe, so did its plumbing technology, waste-removal regulations and passion for bathing. Eventually even the empire’s extremities had baths and toilets, and the “barbarians” of the north were finally introduced to the pleasures of washing. But just how did this affect public health?

“It’s difficult to study the prevalence of most infectious diseases because they don’t leave much evidence,” says Mitchell. “But what you can track are parasites.” They often leave clearly identifiable traces. Intestinal worms have eggs with walls that can survive millennia in coprolites – preserved faeces – and persist at burial sites in soil within the pelvic region of long-vanished bodies.

The more delicate cysts of parasitic amoebae, such as those responsible for dysentery and giardiasis, rarely survive intact but can be identified from proteins unique to each species. External parasites such as fleas, lice and ticks also survive at archaeological sites, clinging to fragments of ancient cloth, the teeth of combs, and in soil from graves. More than just a nuisance, they can transmit bacteria responsible for potentially fatal diseases such as typhus and plague.

To establish how baths and toilets affected the health of Britons, Gauls, Germans and other Europeans, who had never seen either before the Romans arrived, Mitchell dug out every reference to parasites found at archaeological sites before, during and after the Roman period. Searching records from more than 50 sites, he mapped changes in the distribution of species over the centuries.

When the Romans invaded, the dominant internal parasites were roundworm (Ascaris lumbricoides), whipworm (Trichuris trichiura) and Entamoeba histolytica, the amoeba that causes dysentery. All three are spread in food or water contaminated with human faeces. With the adoption of toilets and baths, Mitchell expected to see a decline. There was none.

Of the 12 species of internal parasite found in Roman remains, including various tapeworms, flukes and nematodes, those linked to faeces continued to be the most widespread, especially whipworm, the most widely found intestinal parasite in the Roman Empire.

“For all their sophisticated sanitation, under the Romans intestinal parasites did not decrease,” Mitchell says.

Despite the building of baths, fleas and lice – head, body and pubic – also clung on, their numbers undiminished. And there was another surprise. Mitchell expected to see evidence of more exotic parasites, brought to the northern territories by Roman soldiers, officials and traders who had travelled from warmer parts of the empire. Instead, he saw traffic in the opposite direction. Before the Romans, the fish tapeworm had a limited distribution, in what is now France and Germany. During the Roman period, it spread as far as Poland in the east, Britain in the north and Israel in the south.

Why didn’t Rome’s sanitation revolution make a dent in Europe’s dirt-loving parasites? Closer inspection of Roman baths and toilets provides plenty of clues. Take baths. The Romans and their subjects certainly did. Bathing was a communal activity: the largest known baths could take 3,000 people at a time, clean and dirty, healthy and sick. No one used soap. People preferred to be slathered in oil and scraped clean with a curved implement called a strigil. Writers of the time complained about scummy water contaminated by oil and excrement.

“No one knows how often the bathwater was changed,” says Craig Taylor, an archaeologist at the University of Alberta, in Canada.

We don’t know how often they washed their clothes or whether they boiled them. If they put clean bodies into dirty clothes they’d still have ... parasites

This meant there was a significant risk of contracting something nasty. Celsus, a 1st-century writer on medical matters, warned of the dangers of gangrene from bathing with an open wound. The intact could also leave with more than they bargained for. Traces of excrement combined with warm bathwater would have encouraged the spread of roundworm and whipworm eggs if bathers swallowed any water, says Mitchell. Eventually there was some recognition that sharing a bath with the unwell might be unwise: the 1st-century emperor Hadrian ordered that the sick and healthy should bathe at different times – the sick first.

The persistence of fleas and lice is more puzzling; you would think regular baths would get rid of them. Perhaps bathing wasn’t as popular in the northern reaches of the empire, or perhaps Roman hygiene was lacking in another area.

“We don’t know how often they washed their clothes or whether they boiled them. If they put clean bodies into dirty clothes they’d still have ectoparasites,” Mitchell says.

If baths were dirty, toilets were worse. Those in private homes and tenements were often sited in the worst possible place: in or next to the kitchen. Most emptied into cesspits, which was considered preferable to linking to a sewer.

“Roman toilets didn’t have traps, so where they were connected to the sewers there were problems of smells coming back into the home, and the possibility of vermin,” says Taylor.

In Rome itself, the river Tiber regularly flooded. When it did, anyone connected to the sewers could expect a deluge of filthy water, and worse, to pour into their homes.

Public latrines had more mod cons. A continuous stream of water ran through a trench beneath the seats, flushing waste into a sewer. Some provided the Roman equivalent of toilet paper – a sponge on a stick, with a water-filled channel in the floor to rinse it in. Later designs could be positively luxurious, with carved marble armrests between each seat, painted walls and washbasins (but no soap). Nevertheless, people often chose to relieve themselves elsewhere, as the graffiti in ancient Roman cities attests.

A visit to the latrine was probably unpleasant and only for the desperate, according to archaeologist Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow, author of The Archaeology of Sanitation in Roman Italy. She has looked into more Roman lavatories than most. Aside from the total lack of privacy, she notes, they were almost invariably dark, smelly and potentially dangerous. Noxious gases built up in the trench below and sometimes exploded, sending flames shooting up through the toilets. Rats could bite unwary visitors. The sponges were almost certainly shared. It’s no wonder many public toilets included a shrine to the goddess Fortuna.

That’s not all. The seemingly hygienic habit of removing faeces from Roman towns and cities may have contributed to the spread of disease. Every day, cartloads of cesspit waste trundled out of Rome and much of it was sold to farmers to fertilise their crops, a practice that was probably adopted across the empire. (The collection of “night soil” persisted in Hong Kong until the mid-20th century and may well have been used on fields in the New Territories, as was the practice across the border.)

It’s possible that sanitation laws requiring the removal of faeces actually led to reinfection of the population

“It’s possible that sanitation laws requiring the removal of faeces actually led to reinfection of the population, when they ate locally grown produce contaminated with parasite eggs,” says Mitchell.

So should we write off Roman sanitation as a failure? Not at all, says Mitchell.

“We are looking at things from a modern perspective. You have to see things the way the Romans would see them.” Piped water, sewers, baths and toilets were probably never intended to improve health. The Cloaca Maxima was built to drain mosquito-ridden marshes around Rome. Later sewers were intended mainly as storm drains. And having piped water instead of collecting it from the river in a bucket would have been seen as “practical and time-saving”, Mitchell says. Besides, the Romans didn’t understand the link between good hygiene and health.

“They didn’t know about micro-organisms and they didn’t know how parasites spread,” he says.

One mystery remains. Why did the fish tapeworm migrate right across the empire? Mitchell offers an intriguing explanation.

These parasites are found in fish species that spend all or part of their life-cycle in fresh water. Cooking kills the eggs, and before the Romans came, most infections probably arose from eating dried, pickled or smoked fish. The Romans, however, liked to perk up their meals with lashings of garum, a malodorous mix of raw fish and herbs left to ferment in the sun. Demand was huge, and a product that originated in the Mediterranean was soon being made in more northerly regions, where fish tapeworms were much more common. The stinking liquid was packed in sealed jars and traded round the empire – and the parasite went with it.

New Scientist